Right now Wisconsin is battling the worst coronavirus outbreak in America. The question is why? What about Wisconsin is different from the neighboring states of Michigan, Minnesota and Illinois, where the virus is not spreading nearly as fast?

The answer, at least in part, is politics: specifically, the brand of cavalier, it-will-go-away politics propagated by President Trump and parroted by lower-level Republicans who seem hell-bent on resisting efforts to sustain social distancing and mask wearing when the spread is still low enough to contain — and in Wisconsin’s case, who continue to resist even after infections spiral out of control.

As Trump resumes in-person campaigning and public rallies — with cases rising nationally to their highest level since August — Wisconsin has emerged as a cautionary tale for the rest of the country about what could be coming this fall and winter to places that let politics get in the way of commonsense precautions.

Last month Trump held an outdoor rally in Mosinee that attracted thousands of people, most of whom were not wearing masks. Even as case counts soared, he planned to return for back-to-back rallies in Janesville and Green Bay earlier this month — plans that were scrapped only after the president himself tested positive for the virus.

Wisconsin’s numbers are sobering. The state’s new daily case count cleared 3,000 for the first time. Its seven-day average (2,491) has more than tripled since the start of September. Daily hospitalizations have also tripled over the same period. Nearly 20 percent of Wisconsin’s COVID-19 tests are coming back positive.

Overall, the Badger State has logged 17,437 new cases over the last seven days — more than any other state except the far more populous Texas and California. On a per capita basis, that’s more new cases (299 per 100,000 residents) than any other state except the far less populous Dakotas, and several times more than Michigan (75), Illinois (123) or Minnesota (137).

Meanwhile, on a list of the 100 counties nationwide with the highest number of recent cases per resident, all but two counties with more than 300 cases in the last seven days are located in Wisconsin: Oconto (365), Winnebago (1,439), Shawano (337), Calumet (395), Waupaca (307), Outagamie (1,023) and Brown (1,409).

In total, there are 16 Wisconsin counties on that list — the most of any state. And unlike other hard-hit states such as Idaho, Montana and the Dakotas, Wisconsin’s hot spots aren’t dispersed across vast distances; they’re contiguous and concentrated around cities such as Green Bay in the state’s northeast corner, making the spread harder to contain.

Wisconsin officials have opened a 530-bed field hospital at the state fairgrounds to keep COVID-19 patients from flooding heath care facilities, which Democratic Governor Tony Evers recently characterized as being “on the brink” of collapse.

“We hoped this day wouldn’t come,” Evers lamented. “But unfortunately, Wisconsin is in a much different, more dire place today. There’s no other way to put it: We are overwhelmed.”

As Barry Burden, a political science professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, said that, “Wisconsin has become the poster child for how things can go wrong.”

The most disturbing thing about Wisconsin’s outbreak is that it did not have to be this bad. The problem has been described as “political trench warfare between the Democratic governor and the Republicans who control the state Legislature.” That is technically accurate, but it also makes it sound like both sides are defending equally sensible positions aimed at preventing the spread of COVID-19.

They are not. On the one hand, Governor Evers has repeatedly tried to do everything in his power to contain the pandemic. On the other, Republicans have repeatedly challenged the Governor’s authority and thwarted his efforts, blocking the sort of basic public-health measures other states have enacted while touting themselves as champions of “individual liberty.”

The first and perhaps most consequential of these skirmishes came in the spring, when the Legislature’s Republican leaders filed a lawsuit arguing that the “safer at home” order would leave the state’s economy “in shambles” — even though it was no stricter than dozens of other shelter-in-place orders in effect across the country. On May 13 the state’s Supreme Court, which was also controlled by conservatives, sided with the GOP and overturned the order. Evers was not pleased, saying that the court’s ruling “puts our state into chaos.”

“Now we have no plan and no protections for the people of Wisconsin,” the governor added. “When you have more people in a small space — I don’t care if it’s bars, restaurants or your home — you’re going to be able to spread the virus. And so now, today, thanks to the Republican legislators who convinced four Supreme Court justices to not look at the law but [to] look at their political careers, I guess, it’s a bad day for Wisconsin. It’s the Wild West.”

Bars and restaurants immediately reopened for business. Patrons crowded in. For a while, the state’s case count stayed relatively low, even as the virus surged to record levels in the South and West. But that only bred complacency, and by the time college students started returning for the fall semester, public health efforts had become so politicized that Evers had less power to slow the spread than governors in neighboring states.

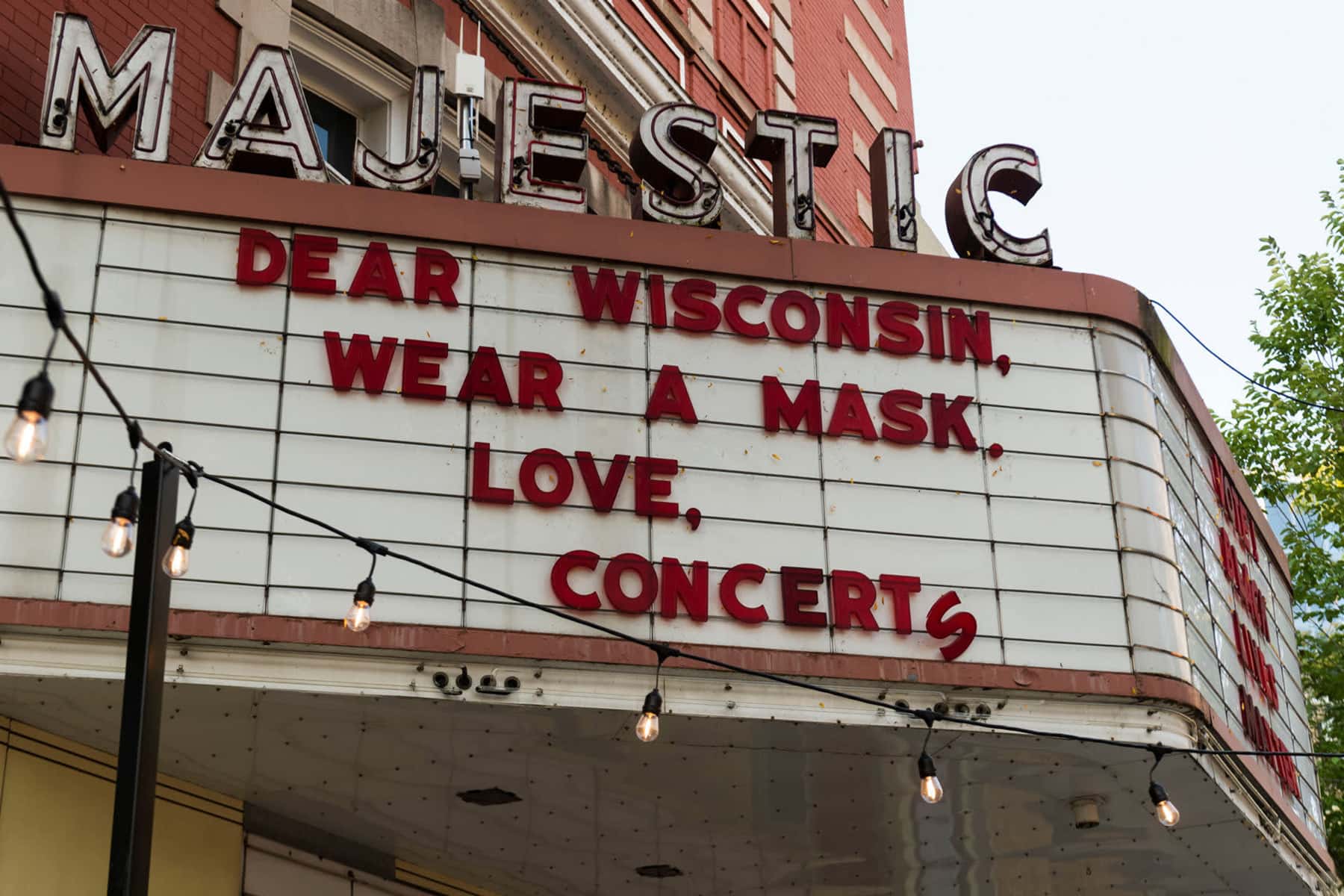

In July, for instance, Governor Evers issued a statewide order mandating masks in enclosed spaces, which he extended last month to November 21. Yet even though nearly three-quarters of Wisconsinites favor Evers’s mandate, Republican lawmakers continue backing lawsuits against it instead of exercising their legislative authority and risk voter backlash.

The same goes for the latest order from the Governor limiting indoor capacity at bars, restaurants and stores to 25 percent as the virus surges. The relentless campaign to delegitimize pandemic precautions as partisan overreach comes with a cost. It discourages compliance. It disincentivizes enforcement. And it preemptively restricts the government’s ability to address a worsening crisis.

Consider the fact that in California and New York, two of the hardest-hit states, indoor dining has only recently resumed at 25 percent capacity despite months of low or declining case counts.

Yet in Wisconsin, people have been drinking and dining indoors since the spring, and it took a full month of exponential spread before Evers felt like he could attempt to limit capacity statewide. Local jurisdictions such as Madison and Milwaukee put limits in place earlier, and today they have lower case counts. But even now, in the midst of America’s worst outbreak, Wisconsinites can still drink and dine indoors. Partly as a result, infections have been radiating outward from college campuses and blanketing the state.

To be sure, Republicans elsewhere have resisted efforts to combat the virus, including in Michigan, where the state Supreme Court ruled recently that Democratic Governor Gretchen Whitmer lacked the authority to extend or declare states of emergency in relation to the pandemic. And of course there has been a reasonable debate to be had over the proper balance between business needs and pandemic precautions.

But Wisconsin is not having that debate. Instead, it has been fulfilling its role as America’s truest bellwether: a state that parallels our divided national politics both in the tightness of its elections and the conflicts that define them. Over the last decade, Republican activism funded by the Koch brothers has clashed with the state’s deep progressive tradition, tipping the scales in the GOP’s favor and exacerbating polarization between left and right, white and black, urban and rural.

After Republicans took control of the governor’s mansion, the U.S. House delegation, one U.S. Senate seat and both chambers of the state Legislature in the 2010 tea party wave, they gerrymandered the state so aggressively that even when Democrats won 53 percent of assembly votes in 2018, Republicans still wound up with 64 percent of the seats.

When Governor Evers took office, Republicans immediately sought to render him powerless for partisan advantage. That was long before the pandemic. Now, with coronavirus cases skyrocketing, the life-or-death consequences of such polarization are becoming harder to ignore.

Аndrеw Rоmаnо