The Republican party has harassed, obstructed, frustrated and purged American citizens from having a say in their own democracy for more than 150 years.

It was a mystery worthy of crime novelist Raymond Chandler. On 8 November 2016, African Americans did not show up. It was like a day of absence. African Americans had virtually boycotted the election because they “simply saw no affirmative reason to vote for Hillary”, as one reporter explained, before adding, with a hint of an old refrain, that “some saw her as corrupt”. As proof of blacks’ coolness toward her, journalists pointed to the much greater turnout for Obama in 2008 and 2012.

It is true that, nationwide, black voter turnout had dropped by 7% overall. Moreover, less than half of Hispanic and Asian American voters came to the polls.

This was, without question, a sea change. The tide of African American, Hispanic and Asian voters that had previously carried Barack Obama into the White House and kept him there had now visibly ebbed. Journalist Ari Berman called it the most underreported story of the 2016 campaign. But it’s more than that.

The disappearing minority voter is the campaign’s most misunderstood story.

Minority voters did not just refuse to show up; Republican legislatures and governors systematically blocked African Americans, Hispanics and Asian Americans from the polls. Pushed by both the impending demographic collapse of the Republican party, whose overwhelmingly white constituency is becoming a smaller share of the electorate, and the GOP’s extremist inability to craft policies that speak to an increasingly diverse nation, the Republicans opted to disfranchise rather than reform. The GOP enacted a range of undemocratic and desperate measures to block the access of African American, Latino and other minority voters to the ballot box.

Using a series of voter suppression tactics, the GOP harassed, obstructed, frustrated and purged American citizens from having a say in their own democracy.

The devices the Republicans used are variations on a theme going back more than 150 years. They target the socioeconomic characteristics of a people (poverty, lack of mobility, illiteracy, etc) and then soak the new laws in “racially neutral justifications – such as “administrative efficiency” or “fiscal responsibility” – to cover the discriminatory intent. Republican lawmakers then act aggrieved, shocked and wounded that anyone would question their stated purpose for excluding millions of American citizens from the ballot.

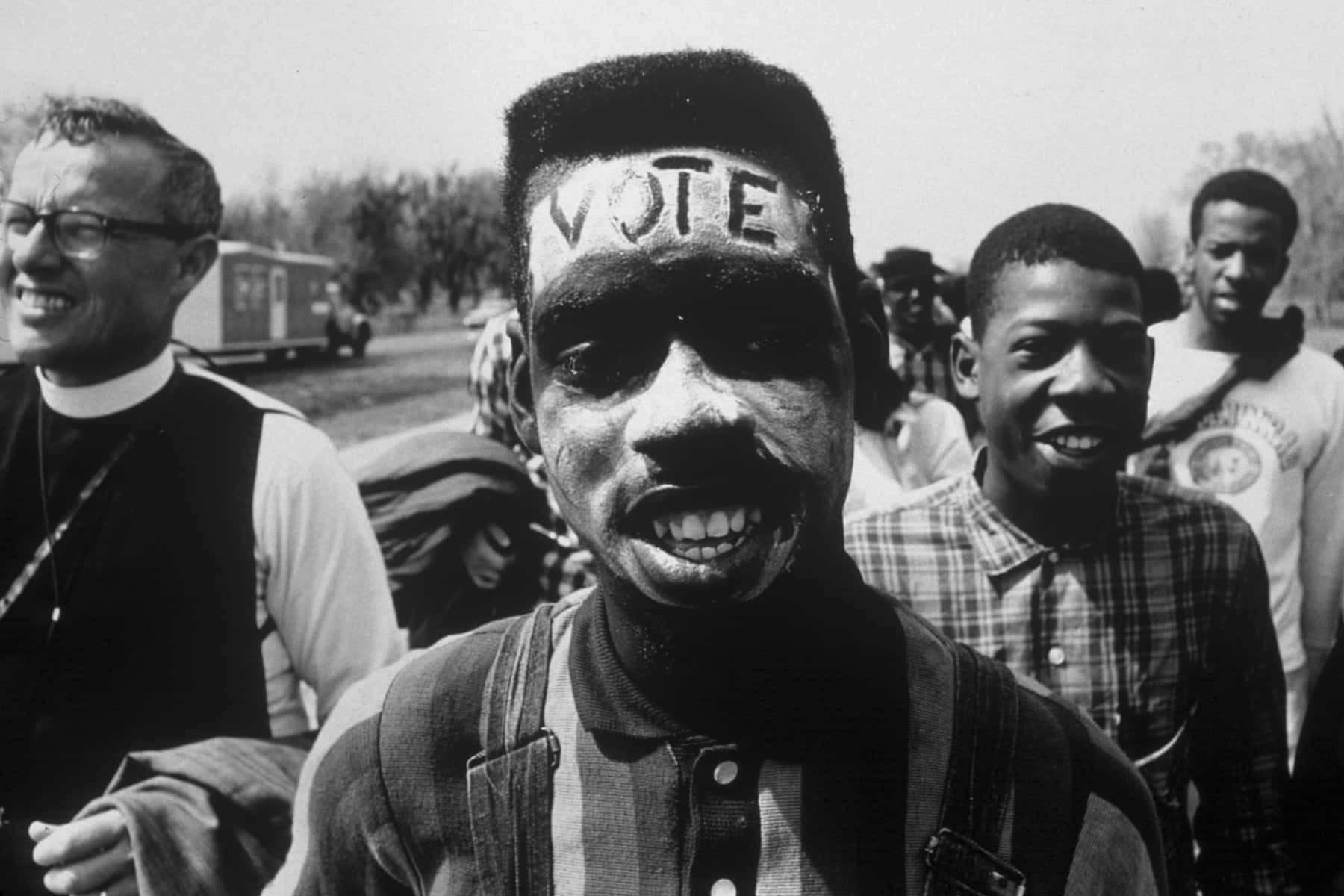

The millions of votes and voters that disappeared behind a firewall of hate and partisan politics was a long time in the making. The decisions to purposely disenfranchise African Americans, in particular, can be best understood by going back to the close of the civil war.

After Reconstruction, the plan was to take years of state-sponsored “trickery and fraud” and transform those schemes into laws that would keep blacks away from the voting booth, disfranchise as many as possible, and, most important, ensure that no African American would ever assume real political power again.

The last point resonated. Reconstruction had brought a number of blacks into government. And despite their helping to craft “the laws relative to finance, the building of penal and charitable institutions, and, greatest of all, the establishment of the public school system”, the myth of incompetent, disastrous “black rule” dominated. Or, as one newspaper editor summarized it: “No negro is fit to make laws for white people.”

Of course, the white lawmakers couldn’t be that blatant about their plans to disfranchise; there was, after all, that pesky constitution to contend with, not to mention the 15th amendment covering the right to vote with its language barring discrimination “on account of race”. Undaunted, they devised ways to meet the letter of the law while doing an absolute slash-and-burn through its spirit.

That became most apparent in 1890 when the Magnolia State passed the Mississippi Plan, a dizzying array of poll taxes, literacy tests understanding clauses, newfangled voter registration rules, and “good character” clauses – all intentionally racially discriminatory but dressed up in the genteel garb of bringing “integrity” to the voting booth. This feigned legal innocence was legislative evil genius.

As the historian C Vann Woodward concluded, “The restrictions imposed by these devices [in the Mississippi Plan] were enormously effective in decimating the Negro vote.” Indeed, by 1940, shortly before the United States entered the war against the Nazis, only 3% of age-eligible blacks were registered to vote in the south.

Senator Theodore Bilbo, one of the most virulent racists to grace the halls of Congress, boasted of the chicanery (of the Mississippi Plan) nearly half a century later. “What keeps ’em [blacks] from voting is section 244 of the [Mississippi] Constitution of 1890 … It says that a man to register must be able to read and explain the Constitution or explain the Constitution when read to him.”

While the Civil Rights Movement and the subsequent Voting Rights Act of 1965 seemed to disrupt and overturn disfranchisement, the forces of voter suppression refused to rest. The election of Barack Obama to the presidency in 2008 and 2012 sent tremors through the right wing in American politics. They seized their opportunity in 2013 after the US supreme court gutted the Voting Rights Act and doubled down on some vestiges of the Jim Crow era, such as felony disfranchisement.

In 2016, one in 13 African Americans had lost their right to vote because of a felony conviction – compared with one in 56 of every non-black voter. The felony disfranchisement rate in the United States has grown by 500% since 1980. In America, mass incarceration equals mass felony disfranchisement. With the launch of the war on drugs, millions of African Americans were swept into the criminal justice system, many never to exercise their voting rights again.

Generally, the incarcerated cannot vote, but once they have served their time, which sometimes includes parole or probation, there is a process – often arcane and opaque – that allows for the restoration of voting rights. Overall, 6.1 million Americans have lost their voting rights. Currently, because of the byzantine rules, “approximately 2.6 million individuals who have completed their sentences remain disenfranchised due to restrictive state laws”, according to The Sentencing Project.

The majority are in Florida. The Sunshine State is actually an electorally dark place for 1.7 million citizens because “Florida is the national champion of voter disenfranchisement”, according to the Florida Centre for Investigative Reporting. The state leads the way in racializing felony disfranchisement as well. “Nearly one-third of those who have lost the right to vote for life in Florida are black, although African Americans make up just 16% of the state’s population,” according to Conor Friedersdorf’s reporting for the Atlantic.

Florida is one of only four states, including Kentucky, Iowa and Virginia, that “permanently” disfranchises felons.

The term “permanent” means that there is no automatic restoration of voting rights. Instead, there is a process to plead for dispensation, which usually requires petitioning all the way up to the governor after a specified waiting period. Republican Governor Rick Scott, a Republican, has made that task doubly difficult. The Florida Office of Executive Clemency, which he leads, meets only four times a year and has more than 10,000 applications waiting to be heard.

An еx-оffеndеr cannot even apply to have his or her voting rights restored until 14 years after all the sentencing requirements have been met. The process is therefore daunting enough as it is, but Scott has slowed it down considerably.

His predecessor, a moderate Republican turned Democrat, “restored rights to 155,315 ex-offenders” over a four-year span. Since 2011, however, Scott has approved only 2,340 cases.

Republicans in Georgia have brought their own distinct twist to voter suppression. Secretary of State, Brian Kemp, has developed a pattern of going after and intimidating organizations that register minorities to vote. In 2012, when the Asian American Legal Advocacy Center (AALAC) realized that a number of its clients, who were newly naturalized citizens, were not on the voter rolls although they had been registered, its staff made an inquiry with the secretary of state’s office.

After waiting and waiting and still receiving no response, AALAC issued an open letter expressing concern that the early voting period would close before they had an answer. Two days later, in a show of raw intimidation, Kemp launched an investigation questioning the methods the organization had used to register new voters. One of the group’s attorneys was “aghast … ‘I’m not going to lie: I was shocked, I was scared.’” AALAC remained under this ominous cloud for more than two years before Kemp’s office finally concluded there was no wrongdoing.

Kemp then went after the New Georgia Project when in 2014 the organization decided to whittle away at the bloc of 700,000 unregistered African American voters in the state and, in its initial run, registered nearly 130,000 mostly minority voters. Kemp didn’t applaud and see democracy in action. Instead, he exclaimed in a TV interview, “We’re just not going to put up with fraud.”

Later, when talking with a group of fellow Republicans behind closed doors, he didn’t claim “fraud”. It was something much baser. “Democrats are working hard … registering all these minority voters that are out there and others that are sitting on the sidelines,” he warned. “If they can do that, they can win these elections in November.” Not surprisingly, within two months of that discussion, he “announced his criminal investigation into the New Georgia Project”. And, just as before, Kemp’s hunt for fraud dragged on and on with aspersions and allegations filling the airwaves and print media while no evidence of a crime could be found.

Vote suppression has become far too commonplace. In 2017, “99 bills to limit access to the ballot have been introduced in 31 states … and more states have enacted new voting restrictions in 2017 than in 2016 and 2015 combined”, according to Abi Berman.

Yet, while there are far too many states that are eager to reduce “one person, one vote” to a meaningless phrase, others, such as Oregon, are determined to “make voting convenient” and “registration simple” because these “policies are good for civic engagement and voter participation”. In 2015, Oregon pioneered automatic voter registration (AVR). Under AVR, Oregon added 68,583 new voters in just six months. By the end of July 2016, the state’s “torrid pace” had swelled the rolls by 222,197 new voters.

California took one look at its neighbor to the north and is “hard on Oregon’s heels”. Secretary of State, Alex Padilla, dissatisfied with his own state’s abysmal 42% voter turnout rate, had been scouring the nation looking for best practices. “We want to serve as a contrast to what we see happening in other states, where they are making it more difficult to register or actually cast a ballot,” he said.

California, thus, adopted and then adapted Oregon’s AVR program to include preregistration of 16- and 17-year-olds who are then automatically registered to vote when they turn 18. These state initiatives to remove the barriers to the ballot box including the use of mail-in ballots, which has had tremendous success in Colorado, are beginning to ricochet around the nation. To date, ten states have implemented AVR and “15 states have introduced automatic voter registration proposals in 2018”.

Democrats in Congress have also pushed for legislation to enact a federal AVR program, because the United States consistently ranks toward the bottom of developed democracies in terms of voter turnout. In July 2016, Senators Patrick Leahy (D-VT), Dick Durbin (D-IL), and Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) co-sponsored legislation that would take AVR nationwide. Leahy remarked, “There is no reason why every eligible citizen cannot have the option of automatic registration when they visit the DMV, sign up for healthcare or sign up for classes in college.”

No reason at all, except not one Republican in Congress has stepped up to support the bill.

Thus, when thirty-one states are vying to develop new and more ruthless ways to disfranchise their population, and when the others are searching desperately for ways to bring millions of citizens into the electorate, we have created a nation where democracy is simultaneously atrophying and growing – depending solely on where one lives.

History makes clear, however, that this is simply not sustainable. It was not sustainable in the antebellum era. It wasn’t sustainable when the poll tax and literacy test gave disproportionate power in Congress to Southern Democrats. And it’s certainly not sustainable now. Or, as Abraham Lincoln soberly observed, “I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.”

Carol Anderson

Library of Congress

Originally published on The Guardian as A threat to democracy: Republicans’ war on minority voters

Help deliver the independent journalism that the world needs, make a contribution of support to The Guardian.