By Jennifer Martinez-Medina, PhD Candidate/Political Science Instructor, Portland State University

Ivan Ocon thought he would be headed back to civilian life as a U.S. citizen after serving the U.S. Army in Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003.

Ocon, who was born in Mexico, came to the United States as a legal permanent resident in 1985 to reunite with his mother. He joined the Army in 1997, and his recruiter assured him that enlisting would make him a U.S. citizen. When Ocon received orders of deployment to Iraq he was given a pre-deployment checklist to help him get his affairs in order. Confirming his immigration status wasn’t on that list, because citizenship is not required for overseas military service.

Ocon deployed as a noncitizen. He figured if he made it home alive, he would finish the naturalization process. Instead, Ocon was convicted of a crime and jailed in 2007, released for good behavior after nine years, and summarily deported. Today, he is stranded in Ciudad Juarez, Mexico, separated from his family and fighting to come home.

PTSD-related crimes

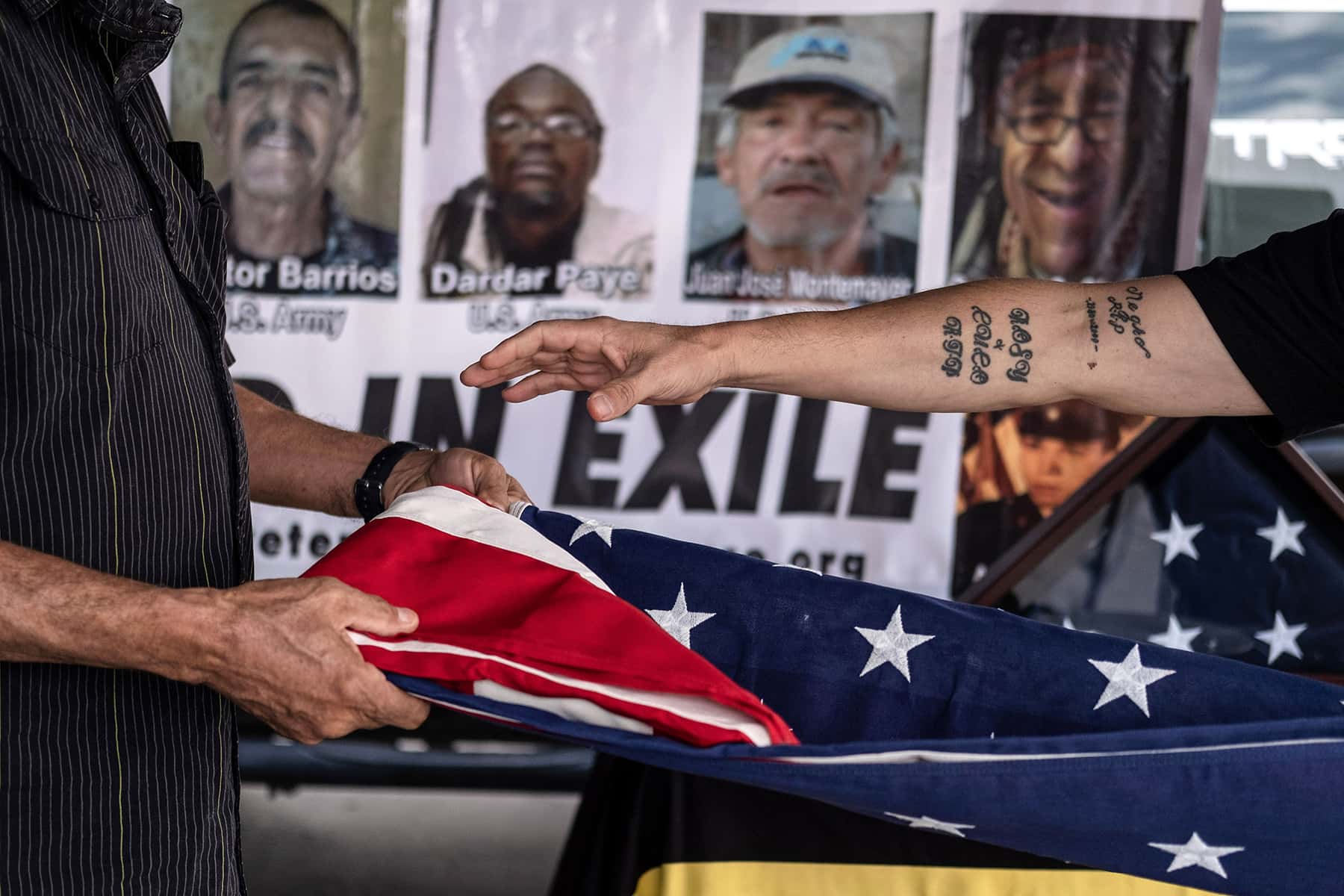

As of 2018, the United States had 94,000 noncitizen military veterans. Ocon is one of at least 92 to be deported between 2013 and 2018, according to data from Immigration and Customs Enforcement and other agencies. The majority – 78%, according to federal data – were removed because of criminal convictions. Under the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigration Responsibility Act, “aggravated felonies” are a basis for automatic deportation.

Struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder and substance abuse put veterans at greater risk of incarceration than the general population. In 2017, nearly 28% of minority veterans – that’s 1,315,989 people – reported a service-connected disability, principally PTSD.

Veterans without U.S. citizenship are therefore acutely susceptible to deportation. The American Civil Liberties Union suggests that many veterans are deported as a result of criminal convictions that stem from PTSD symptoms. Intimate-partner violence and drug convictions are common crimes.

Unfulfilled promises

I am a political scientist who studies political rights across borders. I began collecting deported veterans’ stories after my brother, a U.S. Army veteran, was deported to Mexico in 2005. So this work, and this problem, is personal for me. Military service is supposed to qualify veterans for naturalization as U.S. citizens – and extends status benefits to family members – because honorable service satisfies the “good moral character” requirements for naturalization, according to the 1940 Nationality Act.

The promise of naturalization is sometimes a military recruitment strategy targeting immigrant communities. After 9/11, immigrant military members even became entitled to expedited citizenship, which could speed up the naturalization process from three years to one year.

But in 2017 a Trump administration policy restricted access to the expedited citizenship promised to veterans after 9/11. And, in general, immigrant veterans get very little guidance about how to complete the naturalization process from their military branches once they have served.

This systemic failure, combined with a lack of coordination among ICE and other government agencies, has left more than half of the eligible noncitizen service members in administrative and legal limbo.

Repatriation efforts

In Ivan Ocon’s case, the aggravated felonies that got him deported were aiding and abetting a kidnapping and brandishing a firearm – secondary charges related to a 2007 crime committed by his brother. After being released from jail for good behavior in 2015, Ocon spent the next 11 months fighting the automatic deportation order that is issued when an immigrant is convicted of a crime.

He filed an application in late 2015 for naturalization based on wartime service, but despite his having earned over 10 military medals and ribbons, the Department of Homeland Services six months later denied his application, saying Ocon lacked “good moral character.”

He was deported to Juarez soon after.

With “no money and nothing but time,” Ocon now serves as a bridge for veterans navigating deportation. He describes his advocacy at the Deported Veteran Support House Juarez Bunker as “Kicking up dust for the veterans that don’t or can’t.”

Deported veterans are using a variety of strategies to make their case for returning home, with many focused on the new administration in Washington, D.C.

President Joe Biden’s recently released plan to reform the U.S. immigration system promises a pathway to citizenship for the 11 million undocumented immigrants and Dreamers in the U.S. But it makes no mention of reuniting with U.S. family members the millions more who were deported or voluntarily returned to their country of origin, such as deported veterans.

Immigrant veterans hoping Biden will consider their plight have found a congressional ally in Sen. Tammy Duckworth. On Jan. 20, Duckworth asked Biden for a series of executive actions that would stop the deportation of veterans and begin the repatriation process.

The Biden administration responded by announcing a review of veteran deportations under the Trump administration – a time frame deported veteran advocates say is too narrow. Several hundred veterans deported before 2017 – among them Ocon – are living in banishment.

Deported veterans are also allying with other immigrant communities to push the New Way Forward Act, a bill that would redefine categories of deportable crimes and allow judges to take military service into consideration before issuing a removal order.

The bill, which was reintroduced by Rep. Jesus “Chuy” Garcia of Illinois on Jan. 26, could make 50% to 60% of deported veterans eligible to return home, veteran advocate Robert Vivar told me.

On Presidents Day, Garcia joined deported veterans and their coalition at a virtual press conference unveiling the “Leave No One Behind Mural Project.”

This arts initiative will create murals in cities across the U.S. depicting the stories of the immigrants who remain excluded from Biden’s proposed immigration reforms, starting in March and unveiling a new mural every few weeks through the end of Biden’s 100 days.

Ocon is part of the mural project. He sees art and lobbying as “fighting the same battle” for deported veterans, “but on different fronts.”

Guіllеrmo Аrіаs and Hеrіkа Mаrtіnz

Originally published on The Conversation as Deported veterans, stranded far from home after years of military service, press Biden to bring them back

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.