By Joel Christensen, Professor of Classical Studies, Brandeis University

President Joe Biden began his presidency by memorializing the 400,000 American lives that had been lost up to that point to COVID-19.

The ceremony, held on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, was arguably the first official moment of nationwide public mourning in the United States.

“To heal, we must remember,” Biden said. “It’s important to do that as a nation.”

But how do we acknowledge our collective suffering as the toll of the pandemic continues to grow, with hundreds of thousands possibly undercounted? How do we talk about healing or justice when the mortality rates in communities of color are so much higher?

As a scholar of Greek literature, I argue that ritual practices from ancient Athens, particularly its plays and communal theatrical events, may have some answers to these questions.

Mourning mass tragedies

In ancient Athens, leading politicians commemorated military deaths by offering an annual “epitaphios” – a funeral speech for those who died fighting for the city. But these official speeches were not the only public forms of mourning and remembrance. Ancient Athenians also held annual competitions in which playwrights responded to events “in real life” through myth and storytelling.

For example, the story of Oedipus and the plague on Thebes, describing how the mythical king struggled to cope with the plague caused by his own murder of his father, was performed as the city reeled from a siege and a plague of its own in 429 B.C.

For ancient Greeks, this ritualized storytelling, or “tragic performance,” had a therapeutic effect. It created a context to explore and process individual and collective experiences of loss and trauma. Psychologist Peter Kellerman has described this sort of experience as a “milestone event.”

Indeed, the Greek philosopher Aristotle suggests something like this in his “Poetics,” a treatise on tragedy and performance. By identifying with characters and experiencing vicarious pain and fear, he argues, audiences achieve “catharsis.” Catharsis is a difficult thing to define, but philosopher Martha Nussbaum has described it as a “clarification of who we are.”

Storytelling, community and grief

Even though we live our lives in relationships with others, traumas are often not shared. But collectivizing emotion through storytelling can be a critical step in recovering from traumatic events. Experiencing and processing grief together provides people with the emotional capacity to articulate how trauma has changed them.

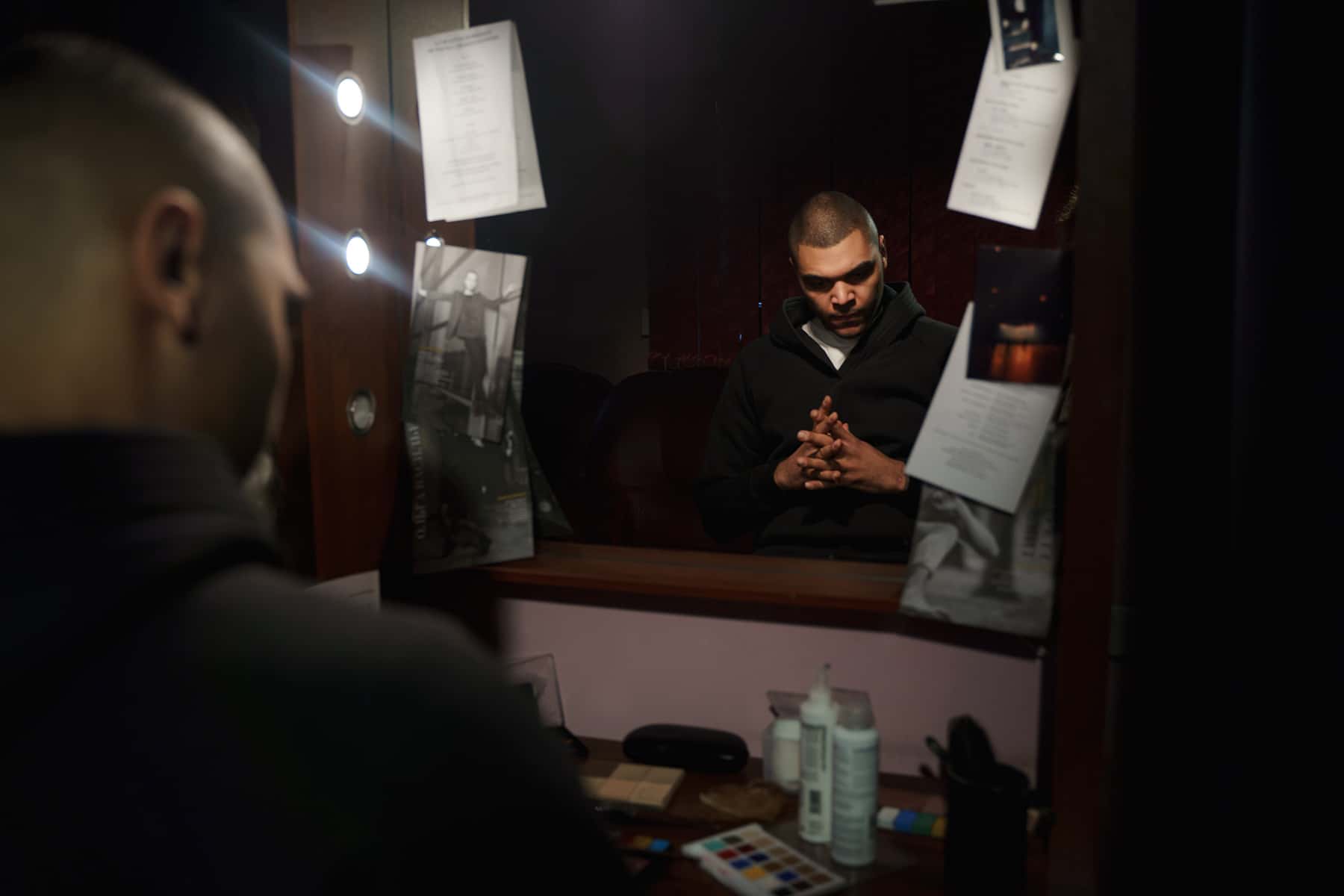

I and some fellow scholars of ancient Greece – including Paul O’Mahony, founder of Out of Chaos Theatre, and with the support of Harvard University’s Center for Hellenic Studies – have experienced this ourselves over the course of the pandemic. We began producing the series “Reading Greek Tragedy Online” to keep busy and connected during lockdown. But in the process, it has taught us a lot about the tangible impacts of tragic performance.

Participants have found that their lived experiences of the pandemic reshaped the meanings of the plays. Euripides’ “Helen,” a story about an alternative Helen who never went to Troy, became a narrative of isolation and loss of control. The political concerns of participants on the day following the U.S. presidential election sharpened the performance of Aeschylus’ “Eumenides,” which tells the story of the uneasy compromise between the goddesses of vengeance the the gods of law in the creation of trial by jury.

The biological basis for catharsis

For a few decades now, both neurobiologists and literary theorists have talked about “mirror neurons” that fire in the same places in the brain when one is either performing an action or watching someone else perform it. The understanding has grown that “vicarious emotion” – like crying over the death of a fictional character – creates some of the same neurological feedback as real-life experiences. This echoes Aristotle’s idea that something therapeutic really happens when we watch a tragic performance.

This effect is no surprise to practitioners of drama therapy such as psychodrama or playback theater, and some have turned to ancient Greek theater and myth to address contemporary traumas and social ills. Bryan Doerries’ Theater of War applies Greek tragedies to help veterans cope with PTSD. Rhodessa Jones’ Medea Project applies Greek myths, like Medea’s betrayal by Jason and the murder of her children, to the lives of incarcerated women.

It has been nearly a year and a half of mass deaths, lockdowns and social distancing, punctuated by social and political upheavals. Now that America’s top elected leaders are openly acknowledging these enormous losses and traumas, perhaps more people can begin talking openly about what they have faced during the pandemic. Communal theater can offer a template for how to do that – just as it did for the Athenians, even in their worst years.

Cottonbro

Originally published on The Conversation as How theater can help communities heal from the losses and trauma of the pandemic

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.