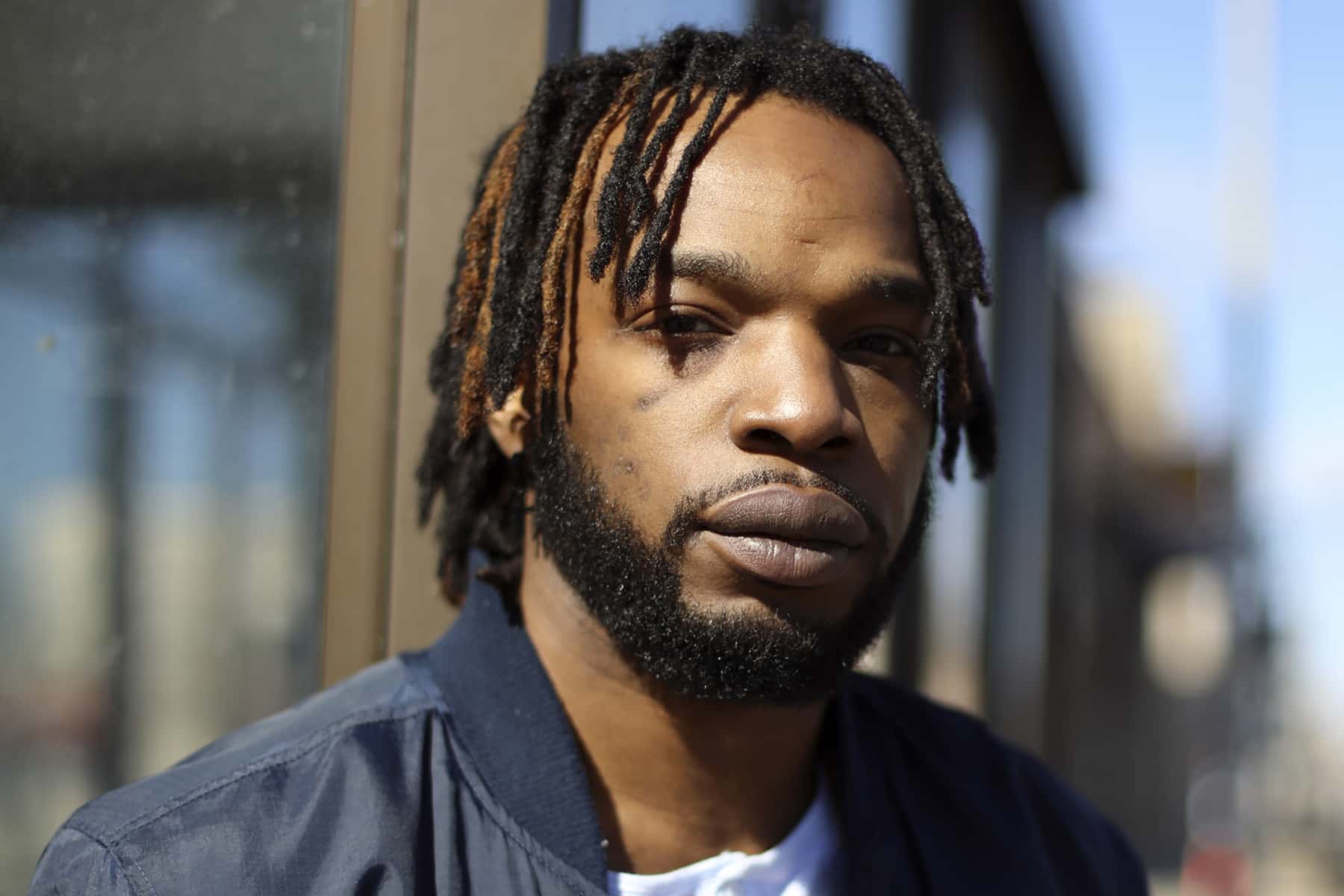

The envelope looked like any other that arrived in the mail, but Jared Cain said he felt violated after looking inside. He saw a ticket for breaking the curfew Milwaukee adopted to regulate protests after a May 25 murder in Minneapolis seen around the world: When police officer Derek Chauvin knelt for more than 9 minutes on the neck of George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man.

Cain did not interact with Milwaukee police during local protests the night of May 31 and early morning June 1, but police cited a video he streamed on Facebook as proof that he was out past 9 p.m. The listed penalty: $691, nearly the median monthly rent for a one-bedroom apartment in Milwaukee.

Cain remembers the night in question. Driving home after saying goodbye to a cousin leaving for the U.S. Army, he noticed blocked-off streets, a car on fire and people everywhere. Cain, a public school teacher and media entrepreneur, said he followed his first instinct and pressed record on his phone camera.

“People need to see this,” he recalled thinking. “There’s no coverage.”

Officers inside Milwaukee’s Fusion Center, a hub in a nationwide network where law enforcement agencies collectively look for criminal and terrorist activity, later spotted Cain’s video on Facebook and issued the citation. Within a week, Cain said FBI agents showed up to his home and asked him whether he was involved with antifa, a loosely organized political protest movement that militantly opposes right-wing ideology.

“I didn’t even know what antifa was,” Cain said. “I was totally baffled, because I thought that they came about the ticket — because the ticket was unlawful.”

The Milwaukee Police Department cited at least 170 people for curfew-related violations between May 30 and June 2, 2020. Police later voided citations against 86 people — in many cases after taking them into custody. At least six people, including Cain, received tickets by mail that cited online footage showing them outside past curfew, according to copies of the citations obtained through a public records request.

Black residents make up about 39% of Milwaukee’s population, but they accounted for 64% of the 162 cited where race was recorded, followed by white (26%), Hispanic (9%) and Asian American (1%) recipients. Documents do not explain why many citations were voided. Explanations on a few range from “entered in error” to a pair invalidated “due to DA refusal to issue charges.”

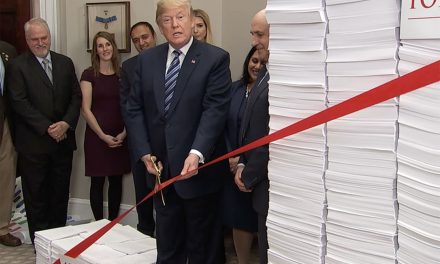

A police department spokesman said “procedural errors” required voiding others. FBI agents visited multiple people cited for curfew violations in Milwaukee, according to attorneys representing some who challenged the infractions. That unfolded as then-President Donald Trump pushed the unsubstantiated narrative that antifa was fomenting violence amid the unrest.

Later in the summer and fall, two other Wisconsin cities — Kenosha and Wauwatosa — enforced sweeping curfews during protests of separate police shootings of Black men, with police arresting dozens of protesters in each city. They were among at least 200 U.S. cities in 27 states that issued curfews during protests last year, according to one tally by the Washington Post.

City officials call curfews a tool for maintaining order during a time when vandalism and violence mix with otherwise peaceful protests. But civil rights attorneys and other critics say the curfews did more to chill speech and intimidate racial justice protesters than to preserve safety.

Officials in Kenosha and Wauwatosa are now defending their curfew enforcement in federal court, and the issue returned to the national spotlight this month as law enforcement in the Minneapolis suburb of Brooklyn Center aggressively responded to protests following the fatal police shooting of 20-year-old Daunte Wright on April 11 — an episode that overlapped a trial that ended when a jury convicted Chauvin of murdering Floyd.

Nicole Muller, an attorney who represented dozens who received citations, said Milwaukee residents remain “traumatized” by last year’s curfew enforcement, and she questioned whether police will handle future protests much differently.

“Over the past 60 years of political organizing, the people of Milwaukee have continuously been met with restrictive curfews and excessive force, trying to claim that what the people were doing was unlawful,” Muller said. “But ultimately, what the city and law enforcement organizations were doing was violating people’s rights to free speech.”

Asked whether Milwaukee police would recalibrate curfew enforcement, Jeff Fleming, a spokesperson for Mayor Tom Barrett, said, “I can tell you every situation presents unique circumstances. Previously, and in future situations, establishing a curfew is not taken lightly.”

In a March 29 email, a Milwaukee Police Department spokesperson said the department is “constantly reviewing our past practices, as well as other jurisdictions’ best practices, to improve our services.” The email confirmed one change following last year’s protests: Police will no longer issue curfew citations by mail.

Curfews trigger lawsuits

Police are more likely to keep protest crowds peaceful by targeting people who endanger the public, while protecting the speech rights of others — rather than through violent crackdowns and mass arrests, decades of research shows. But criminologists are less certain about the precise role that curfews play in public safety.

Edward Maguire, a professor of criminology and criminal justice at Arizona State University, suspects that curfews may prove useful in quelling riots. But he remains unfamiliar with research on the issue, he said, echoing other experts who say such questions remain largely unexplored. Curfew use should be limited to riot control, with enforcement focused on people committing crimes like property damage, violence or theft, Maguire recommended.

“If they are used to quell non-riotous protests, then they run the risk of making people angrier and fueling even more protest activity,” he said in an email. “They also run the risk of violating people’s civil rights, which could lead to costly lawsuits.”

A lawsuit in U.S. District Court in Milwaukee claims that Kenosha law enforcement exclusively arrested about 150 racial justice protesters for violating the county’s curfew — as early as 7 p.m. over nine nights last August and September — while ignoring mostly white armed vigilantes and counterprotesters who also walked the streets at night during unrest after a police officer shot Jacob Blake, a 29-year-old Black man following a domestic complaint. Curfew violations in Kenosha carried a $200 penalty.

Law enforcement made 252 total arrests during that period and Kenosha saw more than $50 million in property damage. One vigilante, 17-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse, faces homicide charges for shooting two people to death after claiming he arrived to protect the city from protesters. He wasn’t arrested until he returned home to Antioch, Illinois.

Meanwhile, 50 people are suing the city of Wauwatosa, alleging they were “ticketed, arrested, and/or harassed,” during October protests after the Milwaukee County district attorney announced that Wauwatosa Police Officer Joseph Mensah would avoid charges for fatally shooting 17-year-old Alvin Cole months earlier. That lawsuit accuses Wauwatosa Mayor Dennis McBride of violating state law by issuing an emergency order and curfew before any unrest and without consent from the city’s Common Council.

McBride — who pushed to reduce curfew penalties from $1,321 to $313 after more than 60 people were cited — broadly denies the allegations. Attorneys for the city and county of Kenosha are also denying wrongdoing while asking the court to dismiss that lawsuit.

McBride called Wauwatosa’s enforcement a “middle path” between “far right” demands for stronger force against protesters and a “far left (that) seemed to believe that protesters should not have to comply with state and local laws.”

“We do not know what might have happened if we had not prepared” for the announcement that Mensah would face no charges, McBride said. “We do know that unlike Kenosha, during the emergency period in Wauwatosa no one was killed, no one was seriously hurt, no serious property damage occurred — and the protests continued each day until curfew time.”

But critics say tough curfew enforcement reinforced racial grievances that seeded unrest in the first place.

“I think mayors who institute curfews are listening to the wrong people. They’re not listening to the decades of science behind the escalation,” said Ryan Clancy, a white Milwaukee County supervisor who was arrested for violating curfew on May 31. “They’re listening to a small, loud group of people who are responding to this misplaced fear, rather than taking a step back and looking at why people are taking to the streets.”

Cain called the citations issued in Milwaukee and Wauwatosa emblematic of how those communities treat Black and brown residents. Cain said he didn’t fully grasp the region’s extreme segregation until he traveled outside of Milwaukee’s North Side, where he grew up. When in Wauwatosa and other suburbs, he feels like residents in the white majority don’t want him there.

“For them to even throw up a curfew in Wauwatosa, in light of something that may happen, is feeding into the segregational thing,” Cain said.

Curfews past and present

Milwaukee police officers have long been the subject of reform debates and civil and criminal proceedings, particularly after police killings. Recent lives lost to police killings include Dontre Hamilton in 2014 and Sylville Smith in 2016. But Milwaukee’s history of racial unrest and curfew clampdowns stretches back decades.

That includes the summer of 1967, when years of racist housing practices and police brutality culminated in a July 30 uprising — with fires and business break-ins — that left four dead and about 100 injured. The National Guard joined police in quelling most violence by the next day, patrolling the city in armored vehicles and enforcing a strict, all-day curfew.

“Street lights shined down on empty sidewalks. In outlying areas of the city, a few brave souls defied the law and were seen taking their dogs for walks,” the Wisconsin State Journal reported on Aug. 1, 1967, citing the curfew’s role in restoring order.

Floyd’s death in Minneapolis came nearly 53 years later as Milwaukee also grieved Joel Acevedo, who died in April 2020 — days after Michael Mattioli, an off-duty Milwaukee police officer, allegedly put him in a 10-minute chokehold during a fight.

Thousands peacefully marched in downtown Milwaukee on May 29, demanding justice for Floyd. Others caravanned past the home of Mattioli, who resigned in September and faces charges of reckless homicide. After 10 p.m., a smaller group of people vandalized and stole from businesses across the city according to media reports. Two police officers suffered minor injuries hours later — one from a shooting — and about 50 people were arrested.

On May 30, Mayor Tom Barrett set a 9 p.m. curfew to “stem the coordinated looting and property damage to private and public property in the City of Milwaukee,” according to his proclamation. Gov. Tony Evers activated 125 National Guard members to help.

“We are actively arresting curfew violators and towing vehicles,” police warned on Facebook the next night: “Go home unless you want to be arrested and have your vehicle towed.”

County supervisor arrested

Among those affected: Clancy, the newly-elected county supervisor. He said he acted as an American Civil Liberties Union legal observer during the day and remained out past curfew on May 31 to engage with constituents.

Clancy posted a video on Facebook of the events leading up to his arrest near the border of Milwaukee and Shorewood, where a small group of protesters milled about. The video shows an armored vehicle rolling down the street and police officers in riot gear blocking movement into Shorewood, a predominantly white village that had no curfew. An officer knocked Clancy to the ground, and officers later zip tied his hands behind his back and loaded him into a vehicle with several others — ignoring that the curfew exempted government officials.

That arrest during the COVID-19 pandemic forced Clancy to later quarantine away from his family. His citation was later voided, and he said he’s considering legal action against the police department and Milwaukee County Sheriff’s Office.

In another instance, police laid spike strips to stop a 27-year-old as he drove down North Sixth Street after midnight on June 2, according to the man’s citation. Officers noted a directive to use the spikes “in areas that had experienced high levels of civil unrest.” The man was “combative,” following the stop, and officers eventually took him into custody, the citation said.

Milwaukee’s curfew stretched three nights before Barrett cited “notable reduction in illegal activity associated with public protests,” in lifting it on June 2.

“I have respect for the thousands of Milwaukee residents who have peacefully demonstrated in recent days, and I hope that all future protests are lawful,” Barrett said at the time.

Curfew disparities

Critics decried the curfew enforcement in a city where police have long disproportionately stopped, frisked or otherwise targeted enforcement in Black-majority neighborhoods. Intuitively, high Black turnout at protests may partly explain citation disparities, Muller said. But misperceptions that Black people pose higher threats to police may also play a role, she added.

Last June, Milwaukee City Attorney Spencer Tearman announced that his office would review each curfew citation and decide whom to prosecute.

“When we have civil unrest, the proclamation and the intent is to gain order in the community — lawfully,” he said. “Once a person has been arrested and detained, taken to a station, whether for two hours or eight hours, I think they will have the message and understand that they need to disassemble in the streets.”

That process should be “remedy enough” for breaking curfew — without adding fines, Tearman added.

Ten months later, however, it remains unclear how many faced curfew penalties in Milwaukee. Tearman’s office would not say how many citations it declined to prosecute nor would it answer related questions.

Muller, one of several attorneys who offered free legal representation to citation recipients, said many were dismissed — but their effects will linger.

“There are a lot of people who are still gonna think twice about going to protest again, because of the negative experience that happened here,” she said.

Kenosha lawsuit: ‘two sets of laws’

In Kenosha, protesters of Blake’s shooting last summer allege that law enforcement practices “two sets of laws — one that applies to those who protest police brutality and racism, and another for those who support the police,” according to an amended complaint filed in October.

“Even though there were both pro-police and anti-police brutality protesters, ONLY anti-police protesters were arrested by Kenosha police officers under this curfew,” according to the federal civil rights lawsuit, which is based on interviews and affidavits of witnesses.

The complaint cites viral footage of Kenosha law enforcement appearing to use friendlier tactics on counter-protesters. That includes an Aug. 25 video showing an officer thanking armed vigilantes and tossing a bottle of water to Rittenhouse — hours before the teenager killed 26-year-old Anthony Huber and Joseph Rosenbaum, 36.

Kenosha law enforcement allowed Rittenhouse — who was seen on video walking past an armored vehicle with his hands up — return to Illinois, where he was arrested. He awaits trial on seven charges, including two charges of first-degree reckless homicide. Prosecutors didn’t add the last charge — breaking curfew — until nearly four months after the shooting. He has pleaded not guilty to the killings, citing self-defense.

Neither the Kenosha Police Department nor the county sheriff’s office responded to requests to comment for this story.

But in asking the court to dismiss the civil lawsuit, the city’s legal team calls the curfew helped curb the “rioting, mayhem, and attacks on person and property” that drew national attention and left parts of Uptown in flames and a 71-year-old man brutally assaulted. Arrested protesters rely on “formulaic conclusions and speculation” in accusing officers of unequal curfew enforcement, the city argues.

Secret declaration in Wauwatosa

Wauwatosa officials say they had already spent months preparing for potential unrest linked to the announcement of whether Mensah would face charges for fatally shooting Cole in February 2020 outside of Mayfair Mall. Then they watched Kenosha erupt.

McBride said he sought to avoid similar violence by enacting a 7:00 p.m. curfew beginning on October 7. That was when Milwaukee County District Attorney John Chisholm announced that Mensah, who was cleared of criminal wrongdoing in two previous deadly shootings, would again avoid charges. The Democratic district attorney called Mensah’s third deadly shooting “objectively reasonable,” in part citing evidence that Cole fired a handgun while fleeing.

Wauwatosa police arrested about 60 people during the weeklong curfew and charged others with attempting to start fires or breaking into businesses. The curfew citations carried a $1,000 forfeiture, with additional court costs that pushed the penalty to $1,321. McBride later asked the city prosecutor to reduce the fines to $200 plus court costs ($313), to prevent the fines from being “unduly punitive.”

He called the curfew successful, yielding only minor injuries and property damage — far less fallout than in Kenosha.

Others saw it differently. Critics included Milwaukee County Executive David Crowley and County Board Chairwoman Marcelia Nicholson, who in an October 12 letter wrote that Wauwatosa’s “overly aggressive” police response “created a more violent, more dangerous situation for everyone in the area of the protests.”

Protesters suing the city described suffering various injuries and emotional distress. Plaintiffs include Alvin Cole’s mother and two sisters. They were arrested on Oct. 8 while trying to leave Wauwatosa; a portion of that encounter was livestreamed. Officers forced mother Tracy Cole from her car, pulled her hair, tased her and punched her in the face multiple times, the lawsuit alleges, adding that she suffered a concussion, cuts to her face and a sprained arm.

The lawsuit alleges Wauwatosa’s curfew was illegal for several reasons, including that McBride on Sept. 30 secretly signed an emergency declaration — before any unrest and without consent of the Common Council, “the only entity with legal authority” to make such a declaration.

Wisconsin law allows local governing bodies to declare emergencies. Chief executive officers have such power only when those bodies can’t meet promptly. McBride did not mention his declaration when the Common Council met on Oct. 6, one day before the curfew went into effect.

He later told council members that local police and Governor Tony Evers’ office asked him to declare the emergency — a move necessary for the governor to activate the National Guard. McBride said preparing for potential unrest required confidentiality. That defense drew mixed reviews from council members, with a majority expressing disappointment.

“We had one man enact a law for a period of a few days, and that law became the basis for most of the police action that happened that weekend,” Alderman Craig Wilson said at an October 13 meeting. A few council members said they believed McBride acted in good faith.

Said Alderman Mike Morgan at the meeting: “This was a very, extremely difficult situation to watch from any perspective.”

But Clancy saw a simpler solution for keeping cities peaceful.

“There is one way to stop people from taking to the streets,” he said. “And that’s to change the conditions that they’re there for.”

Clara Neupert and Jim Malewitz

Coburn Dukehart

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.