Despite smaller turnout, activists saw hopeful signs of determination as Black voters cast ballots, amid a pandemic and barriers to get-out-the-vote efforts.

Early in the morning on Election Day, Angela Lang stood in a conference room in the offices of BLOC — Black Leaders Organizing for Communities — on Milwaukee’s north side, addressing nearly two dozen staff members and volunteers. It was the first time the team was together in the building since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March, said Lang, the group’s executive director. They were gathered on Nov. 3 to build on months of community organizing to get out the vote among African-American voters in Wisconsin’s largest city.

The stakes were immense. A worsening pandemic — and accompanying economic recession — was disproportionately harming people of color, and a nationwide reckoning surrounding racism and policing spurred residents to the streets last summer.

“For me, what I define as success is that we sought out to increase Black voter turnout in the city of Milwaukee,” she told her team. “Despite what happens in the rest of the state, despite what happens to the rest of the country. That’s our slice of the pie.”

During the course of several long days — when record numbers of early and absentee votes were counted in battleground states across the country — Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania flipped, narrowly, from red in 2016 to blue in 2020. Pennsylvania pushed former Vice President Joe Biden’s total electoral college tally over the top, and he declared victory on Saturday.

In Wisconsin, his margin of victory was slim: just 20,539 votes, according to unofficial totals. But voter turnout was stagnant in Milwaukee — and down in primarily Black neighborhoods, an analysis found — at a time when the number of votes cast statewide soared above 2016 levels.

A total of 17 voting wards in Milwaukee were examined, in which at least 85 percent of the voters are Black. The analysis found that the raw number of votes cast dropped in all of them in 2020 compared to 2016. The predominantly Black wards were identified by L2, a widely used proprietary voter database, and total votes cast came from the Milwaukee County Clerk’s Office. In all, voters cast 1,222 fewer votes in those 17 wards than in 2016 — a drop of nearly 11%.

Experts and organizers say that was largely due to pandemic-related hurdles, such as the loss of crucial voter engagement tools including door-knocking, and the fact that Black voters are less likely to favor voting by mail — a method that about 60% of Wisconsin voters used to cast their ballots in 2020. Fear of the pandemic, which has ravaged Milwaukee, created additional barriers, they said.

But get-out-the-vote organizers bristle at the suggestion that Black voters haven’t done their part in the past two elections — particularly in a state where lawmakers have made it disproportionately harder for them to vote.

For Lang, and other activists who worked on get-out-the-vote efforts among the city’s Black and Latino communities, the numbers don’t tell the full story. To them, persuading voters to participate despite the relentless force of the COVID-19 pandemic — coupled with the same obstacles to voting that they faced in 2016 — rendered a numerically flat turnout a victory.

On Saturday, November 7, with an American flag pinned to her hair at the downtown Zeidler Union Square, Lang addressed a jubilant crowd.

“Let me tell you, with all these circumstances, the insurmountable barriers, I am damn proud of my city,” she said. “The fact that we had all of these challenges, and yet you still showed up? Imagine if that work didn’t happen. Imagine if the groups and the organizations didn’t make that happen. We would not be standing here today.”

Milwaukee turnout trails other cities

Overall, nearly 3.3 million Wisconsinites cast ballots in the election, compared to 3.1 million voters in 2016. But the total number of ballots cast in Milwaukee did not increase as some had predicted, remaining nearly flat with fewer than 150 votes separating the total from the 2016 figure of 247,836.

Milwaukee contributed roughly 195,000 votes to Biden’s statewide vote total of 1.6 million – up about 6,000 from what Hillary Clinton won from the city in 2016. Trump also saw a bump of about 3,000 votes in Milwaukee, earning 48,414 votes in 2020, compared to 45,411 in 2016. The main difference from 2016: a drop in votes for third-party candidates.

Because Wisconsin offers same-day registration, the Wisconsin Elections Commission recommends measuring turnout based on all eligible voters, not simply those who registered before Election Day, but eligibility figures are not yet available. The number of people who registered on Election Day also is not yet available.

Examining only voters who registered before Election Day, turnout this year was nearly 78% in Milwaukee, lagging behind other Wisconsin cities. In Green Bay, for example, 84% of registered voters cast a ballot, about the same percentage of those who turned out in Madison. Again, once eligible voter numbers are available for 2020, these turnout percentages will change.

Days before official numbers were released, Lang signaled that regardless of the final tally, BLOC’s success in 2020 would largely be judged by its work to build relationships among organizers and residents.

“The story will be how you all showed up every damn day, you pushed through, you pushed through tears, you pushed through tragedy, you pushed through trauma, to do this work,” Lang told her team on the morning of Nov. 3. That effort has drawn attention from activists and observers throughout the country and news organizations including the New York Times, Washington Post, and NPR.

On Election Day, BLOC activists fanned out to 30 precincts on the city’s north side to act as “voter guardians,” engaging with residents. Working from their homes, some 45 activists called and texted voters throughout the day to urge them to vote.

Pandemic changes tactics

In the face of the coronavirus pandemic, organizing tactics necessarily changed. Over the weekend, a ballroom at the Hilton Milwaukee City Center was converted into the nerve center for Leaders Igniting Transformation (LIT), which mobilizes young people of color. There, canvass manager Princeton Jackson kept tabs on the 19 people out in the field dropping literature on doorsteps and running text and phone banks.

Because of the pandemic, door-knocking, usually a highly effective tactic, was off the table, Jackson said. Instead, the group’s operations went fully digital. By the end of Election Day, he said, the group had sent out 1.7 million text messages and placed 913,000 calls. In the two weeks between the start of early voting and Election Day, LIT organizers left literature at 49,700 doors — mostly in Milwaukee’s deeply segregated Black and Latino-majority neighborhoods.

The pandemic “definitely tested our ability to, essentially, evolve or die,” he said. “I think we did a pretty good job in terms of pivoting and just making those necessary changes to ensure that we still galvanize, organize and encourage as many people as we can to exercise their right to vote, especially during such a pivotal time in our nation’s history.”

Democratic political strategist Sachin Chheda said the cancellation of door-to-door canvassing and other community engagement efforts likely hurt turnout in the city.

“In Milwaukee, I think we’ve lost everything in terms of those interactions,” he said. “When you think about what it takes to get a first-time voter to the poll, when you think about what it takes to convince somebody who is economically oppressed that voting is going to make a difference, it requires a level of engagement in person, and missing that, I think, really did have an impact.”

‘Joyful’ Election Day

Nevertheless, spirits were high on Election Day among those venturing to the polls, said Jennifer Epps-Addison, network president at the New York-based Center for Popular Democracy, a national progressive group that organizes for racial and economic justice. Her group had trained — virtually — activists in seven states, including Wisconsin, to serve as election observers.

“There was a lot of excitement across the city, and people participating in voting,” said Epps-Addison, a Milwaukee native. “You know, the line that I kept using is, ‘Have a joyful Election Day,’ and people really were feeling joyful as they went to the polls.”

In some ways, joy is also a tactic. Outside of the Fitzsimonds Boys & Girls Club, a polling place in Metcalfe Park, BLOC activists Dawonyae Robinson, Dawn Holt and Shanice Jones, all 21, danced, sang and handed out shirts and masks that read “Count Every Vote.”

“We came out here, we had a great day, enjoyed ourselves,” said Robinson, his voice hoarse by 5 p.m. “Some people walked up angry, left happy. Some people walked up happy and left even happier. So that made our day a lot better and it made it go very smoothly.”

Midway through the day, somebody called the police with allegations of electioneering that reached the District Attorney’s office. The office declined to pursue the matter, but Robinson said it deterred some would-be voters — police presence at the polls can be intimidating or off-putting to some — and the group had to put their signs away. But the interaction did not dampen their spirit.

Robinson cannot vote, a condition of being on probation. That motivates his activism, he said, and his chant for the day: “I can’t vote, but you can. It’s so important because I need people to take my place in this voting situation.”

2016 saw voter dissuasion effort

Black voters face hidden challenges on their way to the polls. An investigation based on leaked documents showed the 2016 campaign of President Donald Trump used demographic data to systematically dissuade voters in Milwaukee’s primarily Black neighborhoods from participating in the election.

An analysis of the data by Channel 4, a British news organization, found that Black voters made up a disproportionate share of the group identified as “deterrence” voters, or voters the Trump campaign sought to dissuade through Facebook ads. Brad Parscale, former senior advisor to the Trump campaign, offered a later debunked claim that the campaign never targeted the Black community.

In one Milwaukee voting ward in 2016, where 80% of the residents are Black, 44% were marked for deterrence. Of that group, only 36% turned out to vote, according to the analysis. That was why, in 2016, when some cited lower turnout among Black voters in Milwaukee as a factor in Trump’s narrow 22,748-vote win over Hillary Clinton in Wisconsin, activists were unhappy.

They viewed those numbers as part of a trend in which Wisconsin Republicans pushed for years to make voting more difficult, including by enacting voter ID requirements that disproportionately discourage Black voters.

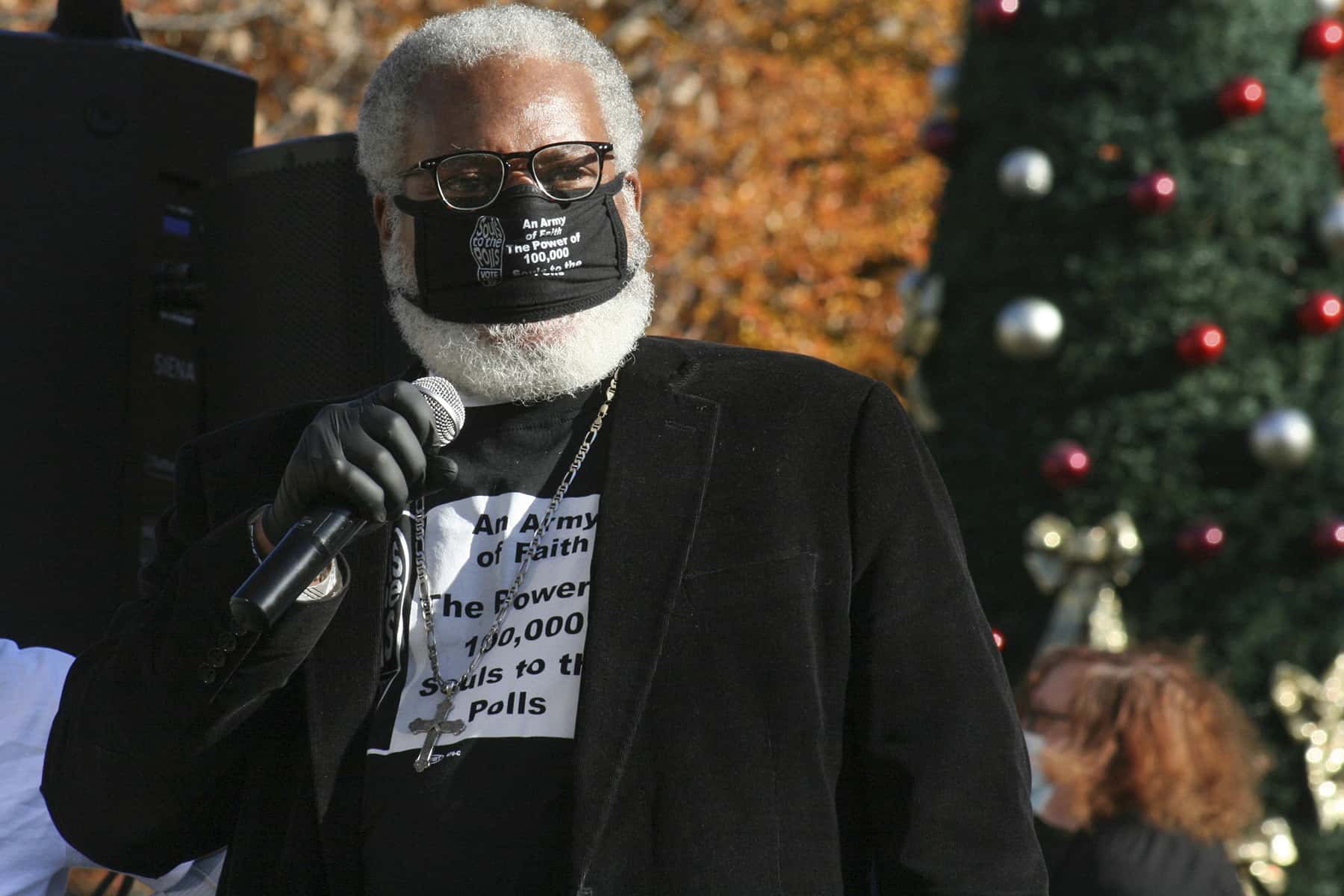

At the Zeidler Square victory celebration Saturday, the Rev. Greg Lewis, executive director of Souls to the Polls Milwaukee, pushed back against the idea that Milwaukee’s turnout had missed the mark. Lewis pointed to challenges facing voters, such as voter ID requirements, a still-pending court case aimed at purging 130,000 voters from the rolls and the shortening of the early voting period to two weeks.

A survivor of COVID-19, Lewis also identified extra hurdles to voting caused by the pandemic, perhaps most clearly illustrated during the April 7 primary, when 180 polling places in Milwaukee were reduced to just five.

“We have to fight all those things. And we still came out, and we voted,” he told a cheering crowd. “I don’t want to hear about anybody talking about depressed voting in Milwaukee. You ought to be talking about those politicians who are suppressing our vote here in Milwaukee.”

Black voters key constituency

Nationwide, voting experts pointed to the role that Black voters played in this year’s election, and especially in urban cores such as Detroit, Philadelphia and Atlanta, where the outcome in these cities drove the outcome for the state. But even as Black voters turned out overwhelmingly for Biden, the Trump ticket saw a small uptick in its support from African-Americans across the country, including in Wisconsin. Trump’s support from Black voters increased by two percentage points to 8% from the 6% of that vote he garnered in 2016.

Some prominent Black celebrities, including rappers Lil Wayne and Ice Cube, expressed support for Trump in the campaign’s final days, and some polls indicated a higher-than-expected favorability towards Trump among Black men.

In Wisconsin, the Trump campaign courted Black voters via its Black Voices for Trump campaign, which emphasized the president’s record on issues like criminal justice reform and school choice. Republicans established their first-ever Milwaukee field office in February, signaling an attempt to reach Black voters. At least one prominent billboard in the city proclaimed Trump’s record on Black unemployment.

Henry Fernandez, principal at the African American Research Collaborative, a polling firm, cautioned against overstating that shift.

“Neither rappers in my age group nor polls that under-sample black men should be used to get the pulse of the Black community,” he said. Black men comprise “the second most progressive voting bloc in America; only Black women perform better for progressive and Democratic candidates, with 92% of black women supporting Biden,” he said.

“Black men, Black women and other people of color, were the only reason this election came out the way it did,” he said.

That’s in the face of ongoing obstacles, including a historic preference for in-person voting and a competing fear of contracting COVID-19, said Kevin Morris, a voting rights researcher at the Brennan Center for Justice, a New York University Law School-based center that advocates for changes to improve democracy.

“Racial minorities, for a number of reasons, didn’t shift as much to vote-by-mail options this year as white voters did,” Morris said. “Especially Black voters are less trustful of voting by mail. And they’re less trustful that their ballot will count. And so it isn’t a seamless process for them to switch how they vote.”

That sentiment is compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic, cases of which climbed precipitously in the weeks leading up the election, and which has disproportionately harmed Black communities nationwide, including in Milwaukee.

In general, Morris said, voters are less likely to turn out if they are sick themselves, or caring for a loved one, “or there are disruptions in their life.”

Coming out of her polling place at Gwen T. Jackson School in the Lindsay Heights neighborhood, Carolyn Dillard said she never considered anything but voting in person on Election Day — even though wearing a mask triggers a breathing condition.

“I never do early voting, because I don’t want my ballot to get lost or anything. I go to the polls, so I know I did it properly,” she said, echoing a theme that activists say they heard during get-out-the-vote efforts.

Even in the face of these challenges, Lang said, a diverse Milwaukee — working class, queer, Black, brown and Indigenous voters — came out.

“I don’t need to tell you how hard this year has been,” she said Saturday, as American flag balloons waved behind her and passing cars honked their support. “And for whatever reason, we all had the audacity to still show up anyways and make our voices heard.”

Vanessa Swales

Coburn Dukehart

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.