By John Joseph Chin, Assistant Teaching Professor of Strategy and Technology, Carnegie Mellon University; and Joe Wright, Professor of Political Science, Penn State

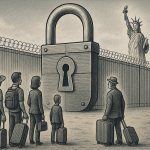

Something unexpected – but hardly unprecedented – happened in South Korea on December 3. With little warning, President Yoon Suk Yeol declared emergency martial law, citing the threat from “pro-North Korean anti-state forces.”

The move, which appeared more about curtailing efforts by the main opposition – the center-left Democratic Party – to frustrate Yoon’s policy agenda through their control of parliament, left many South Koreans stunned. As one Seoul resident told reporters: “It feels like a coup d’état.”

That interviewee wasn’t far off.

As scholars of authoritarian politics and authors of the colpus dataset of coup types and characteristics, we have spent countless hours documenting the history of coups d’état since World War II.

Yoon’s short-lived martial law declaration – it lasted just a few hours before being lifted – was an example of what political scientists call an “autogolpe,” or to give the phenomenon its English name, a “self-coup.”

Our data shows that self-coups are becoming more common, with more in the past decade compared with any other 10-year period since the end of World War II. What follows is a primer on why that’s happening, what self-coups involve – and why, unlike in around 80% of self-coups, Yoon’s gambit failed.

THE COMPONENTS OF A SELF-COUP

All coup attempts share some characteristics. They involve an attempt to seize executive power and entail a concrete, observable and illegal action by military or civilian personnel.

In a regular coup, those responsible will attempt to take power from an incumbent or presumptive leader. Historically, most coups have been perpetrated, or at least supported, by military actors. A classic example is when the Chilean army under Gen. Augusto Pinochet ousted the government of Salvador Allende in 1973 and imposed military rule.

Some coups, however, are led by leaders themselves.

These self-coups are coups in reverse. Rather than the leader of the country being replaced in an unconstitutional manner, the incumbent executive takes or sponsors illegal actions against other people in the regime – for example, the courts or parliament – with the goal of extending their stay in office or expanding their own power.

This may take the form of a chief executive using troops to shut down the legislature, as Yoon tried unsuccessfully to do in South Korea. Others have had more success; Tunisian President Kais Saied orchestrated a self-coup in July 2021 by dismissing parliament and the judiciary to pave the way for expanding his presidential power. More than three years on, Saied remains in power.

Alternatively, a leader may try to coerce state officials or the legislature to overturn an election loss. We saw this happen with Donald Trump after the 2020 U.S. presidential election, and as such we include his attempt to pressure local officials – and then-Vice President Mike Pence – to overturn the election result in our list of “self-coup attempts.”

THE VARIETIES OF SELF-COUP METHODS

But not all executive power grabs are self-coups. For example, if a president gets the legislature to extend presidential term limits and the courts approve – as Bolivian President Evo Morales did in 2017 – this may be a blow to executive constraints and democracy, but we don’t consider it a coup since the procedure for changing the law is constitutional.

In all, we have recorded 46 self-coups since 1945 by democratically elected leaders in the forthcoming self-colpus dataset, including the latest attempt in South Korea. Our self-coup data was compiled over the past three years with the aid of some enterprising undergraduate students at Carnegie Mellon University.

Reviewing the circumstance – and outcomes – of these incidents helps us identify the most common characteristics of self-coups.

Yoon’s actions in South Korea were typical in some ways but not in others. Over half of self-coup attempts in democratic countries target the judiciary or the legislature, while around 40% explicitly seek to undermine democratic elections or prevent election winners from taking office. The rest target other regime elites or a nominal executive.

Yoon declared martial law to grab executive power from an opposition-led legislature.

Interestingly, only a quarter of self-coup attempts in democracies involve such an emergency declaration. Much more common are attacks on opposition parties and leaders and election interference.

About 1 in 5 self-coup leaders suspend or annul the constitution.

Relatively few self-coup attempts in democracies involve attempts to evade term limits, though self-coups that result in so-called “leaders for life” are becoming more common in Africa.

WHY ARE SELF-COUPS ON THE RISE?

Coups and self-coups are two of the most common ways democracies die, though their relative frequencies have changed over time.

Whereas coups were the leading cause of democratic breakdown during the Cold War, self-coups have become the leading cause since the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s.

A third of all self-coup attempts by democratically elected leaders since 1946 have occurred in just the past decade.

Though more research is needed to account for the recent rise of self-coups, we believe part of the answer lies in the decline of anti-coup norms – in which democracies punish coup leaders by withholding recognition, foreign aid or trade deals – and the rise of personalist politics globally.

WHY DO SELF-COUPS FAIL?

Presidents and prime ministers who attempt self-coups presumably think they have a good chance of success – if they didn’t, they wouldn’t attempt a coup in the first place.

The fact that Yoon launched his self-coup bid seemingly without prior support of leaders in his own party is very unusual.

While only half of traditional coup attempts succeed, more than four out of five self-coup attempts by democratically elected leaders succeed, according to our data.

SO WHAT WENT WRONG FOR YOON IN SOUTH KOREA?

Coup success depends on coordinating a lot of people, including partisan allies and military elites. Although overt military support of the kind Yoon initially received is helpful, it is not always decisive.

Most self-coup failures happen when military and party elites defect. The reasons for these defections tend to involve a mix of structural and contingent factors. When masses of people pour into the streets to oppose the coup, like we saw in Seoul, military members can get nervous and defect. And international condemnation of the coup can certainly help overturn self-coup attempts.

Public support for democracy also helps. That’s why self-coups don’t typically happen in long-established democracies like the United States that have accumulated “democratic capital” – the stock of civic and social assets that grows with a long history of democracy.

South Korea, although a military dictatorship from 1961 to 1987, has had decades of democratic rule. And the system worked in South Korea when threatened. Party leaders united to vote unanimously against Yoon.

That contrasts with successful self-coups in the country by Park Chung-hee in 1972 and Chun Doo-hwan in 1980.

WHAT HAPPENS TO FAILED SELF-COUP LEADERS?

Rarely has a failed self-coup leader remained in office for long. The self-coup may lead them to be ousted in a coup, as occurred to Haiti’s Dumarsais Estimé in May 1950. Or they may be impeached, as occurred with Peru’s Pedro Castillo in December 2022.

According to our data, only one failed self-coup leader managed to hang on to office for more than a year to the end of their term. Though not forced from office after the flawed 1994 Dominican elections, Joaquín Balaguer was forced to agree to new elections in 1996 in which he would not be a candidate.

Odds are, then, that President Yoon’s days in power are numbered. Following his attempted self-coup, six opposition parties submitted an impeachment motion against the president. That motion needs 200 of 300 members of the National Assembly to pass.

All 190 present members voted to end martial law, including 18 of 108 members from Yoon’s party. Only a few more of the conservative party’s legislators would have to vote against Yoon for impeachment proceedings to advance.

Threatened by a self-coup, South Korea’s democratic institutions seem to be holding – at least for now.

Ahn Young-joon (AP), Lee Jin-man (AP), AP File Photo, and Cho Da-un (Yonhap via AP)

Originally published on The Conversation under a Creative Commons license as What is a self-coup? South Korea president’s attempt ended in failure − a notable exception in a growing global trend

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.

- Exploring Korea: Stories from Milwaukee to the DMZ and across a divided peninsula

- A pawn of history: How the Great Power struggle to control Korea set the stage for its civil war

- Names for Korea: The evolution of English words used for its identity from Gojoseon to Daehan Minguk

- SeonJoo So Oh: Living her dream of creating a "folded paper" bridge between Milwaukee and Korean culture

- A Cultural Bridge: Why Milwaukee needs to invest in a Museum that celebrates Korean art and history

- Korean diplomat joins Milwaukee's Korean American community in celebration of 79th Liberation Day

- John T. Chisholm: Standing guard along the volatile Korean DMZ at the end of the Cold War

- Most Dangerous Game: The golf course where U.S. soldiers play surrounded by North Korean snipers

- Triumph and Tragedy: How the 1988 Seoul Olympics became a battleground for Cold War politics

- Dan Odya: The challenges of serving at the Korean Demilitarized Zone during the Vietnam War

- The Korean Demilitarized Zone: A border between peace and war that also cuts across hearts and history

- The Korean DMZ Conflict: A forgotten "Second Chapter" of America's "Forgotten War"

- Dick Cavalco: A life shaped by service but also silence for 65 years about the Korean War

- Overshadowed by conflict: Why the Korean War still struggles for recognition and remembrance

- Wisconsin's Korean War Memorial stands as a timeless tribute to a generation of "forgotten" veterans

- Glenn Dohrmann: The extraordinary journey from an orphaned farm boy to a highly decorated hero

- The fight for Hill 266: Glenn Dohrmann recalls one of the Korean War's most fierce battles

- Frozen in time: Rare photos from a side of the Korean War that most families in Milwaukee never saw

- Jessica Boling: The emotional journey from an American adoption to reclaiming her Korean identity

- A deportation story: When South Korea was forced to confront its adoption industry's history of abuse

- South Korea faces severe population decline amid growing burdens on marriage and parenthood

- Emma Daisy Gertel: Why finding comfort with the "in-between space" as a Korean adoptee is a superpower

- The Soul of Seoul: A photographic look at the dynamic streets and urban layers of a megacity

- The Creation of Hangul: A linguistic masterpiece designed by King Sejong to increase Korean literacy

- Rick Wood: Veteran Milwaukee photojournalist reflects on his rare trip to reclusive North Korea

- Dynastic Rule: Personality cult of Kim Jong Un expands as North Koreans wear his pins to show total loyalty

- South Korea formalizes nuclear deterrent strategy with U.S. as North Korea aims to boost atomic arsenal

- Tea with Jin: A rare conversation with a North Korean defector living a happier life in Seoul

- Journalism and Statecraft: Why it is complicated for foreign press to interview a North Korean defector

- Inside North Korea’s Isolation: A decade of images show rare views of life around Pyongyang

- Karyn Althoff Roelke: How Honor Flights remind Korean War veterans that they are not forgotten

- Letters from North Korea: How Milwaukee County Historical Society preserves stories from war veterans

- A Cold War Secret: Graves discovered of Russian pilots who flew MiG jets for North Korea during Korean War

- Heechang Kang: How a Korean American pastor balances tradition and integration at church

- Faith and Heritage: A Pew Research Center's perspective on Korean American Christians in Milwaukee

- Landmark legal verdict by South Korea's top court opens the door to some rights for same-sex couples

- Kenny Yoo: How the adversities of dyslexia and the war in Afghanistan fueled his success as a photojournalist

- Walking between two worlds: The complex dynamics of code-switching among Korean Americans

- A look back at Kamala Harris in South Korea as U.S. looks ahead to more provocations by North Korea

- Jason S. Yi: Feeling at peace with the duality of being both an American and a Korean in Milwaukee

- The Zainichi experience: Second season of “Pachinko” examines the hardships of ethnic Koreans in Japan

- Shadows of History: South Korea's lingering struggle for justice over "Comfort Women"

- Christopher Michael Doll: An unexpected life in South Korea and its cross-cultural intersections

- Korea in 1895: How UW-Milwaukee's AGSL protects the historic treasures of Kim Jeong-ho and George C. Foulk

- "Ink. Brush. Paper." Exhibit: Korean Sumukhwa art highlights women’s empowerment in Milwaukee

- Christopher Wing: The cultural bonds between Milwaukee and Changwon built by brewing beer

- Halloween Crowd Crush: A solemn remembrance of the Itaewon tragedy after two years of mourning

- Forgotten Victims: How panic and paranoia led to a massacre of refugees at the No Gun Ri Bridge

- Kyoung Ae Cho: How embracing Korean heritage and uniting cultures started with her own name

- Complexities of Identity: When being from North Korea does not mean being North Korean

- A fragile peace: Tensions simmer at DMZ as North Korean soldiers cross into the South multiple times

- Byung-Il Choi: A lifelong dedication to medicine began with the kindness of U.S. soldiers to a child of war

- Restoring Harmony: South Korea's long search to reclaim its identity from Japanese occupation

- Sado gold mine gains UNESCO status after Tokyo pledges to exhibit WWII trauma of Korean laborers

- The Heartbeat of K-Pop: How Tina Melk's passion for Korean music inspired a utopia for others to share

- K-pop Revolution: The Korean cultural phenomenon that captivated a growing audience in Milwaukee

- Artifacts from BTS and LE SSERAFIM featured at Grammy Museum exhibit put K-pop fashion in the spotlight

- Hyunjoo Han: The unconventional path from a Korean village to Milwaukee’s multicultural landscape

- The Battle of Restraint: How nuclear weapons almost redefined warfare on the Korean peninsula

- Rejection of peace: Why North Korea's increasing hostility to the South was inevitable

- WonWoo Chung: Navigating life, faith, and identity between cultures in Milwaukee and Seoul

- Korean Landmarks: A visual tour of heritage sites from the Silla and Joseon Dynasties

- South Korea’s Digital Nomad Visa offers a global gateway for Milwaukee’s young professionals

- Forgotten Gando: Why the autonomous Korean territory within China remains a footnote in history

- A game of maps: How China prepared to steal Korean history to prevent reunification

- From Taiwan to Korea: When Mao Zedong shifted China’s priority amid Soviet and American pressures

- Hoyoon Min: Putting his future on hold in Milwaukee to serve in his homeland's military

- A long journey home: Robert P. Raess laid to rest in Wisconsin after being MIA in Korean War for 70 years

- Existential threats: A cost of living in Seoul comes with being in range of North Korea's artillery

- Jinseon Kim: A Seoulite's creative adventure recording the city’s legacy and allure through art

- A subway journey: Exploring Euljiro in illustrations and by foot on Line 2 with artist Jinseon Kim

- Seoul Searching: Revisiting the first film to explore the experiences of Korean adoptees and diaspora