The partisan battle over Wisconsin’s next round of redistricting officially began on August 12 with the release of 2020 U.S. Census data to states.

Though high-level numbers were released in April, the data released on August 12 included the numbers necessary for local and state governments to begin drawing the next set of government district maps across the Wisconsin.

Local governments will be in charge of maps for city and county government, while state lawmakers will draw new district lines for the state’s 99 Assembly seats, 33 Senate seats and eight congressional districts. The maps will be in effect for 10 years after they are drawn.

The map-making process is expected to spur a prolonged fight between the Republican-controlled state Legislature and Democratic Governor Tony Evers, as well as Democratic and Republican advocacy groups.

Evers has called on lawmakers to consider maps that will be drawn by a redistricting commission he created, but GOP leaders have not said they will do so. Evers has the power to veto any maps he does not like, which would send the maps to the courts.

On August 12, Assembly Speaker Robin Vos, R-Rochester, released a statement saying he believes the governor will approve the GOP-drawn maps.

“Soon we will begin the robust map drawing process and I’m confident we will draw a map that the governor will sign,” Vos said.

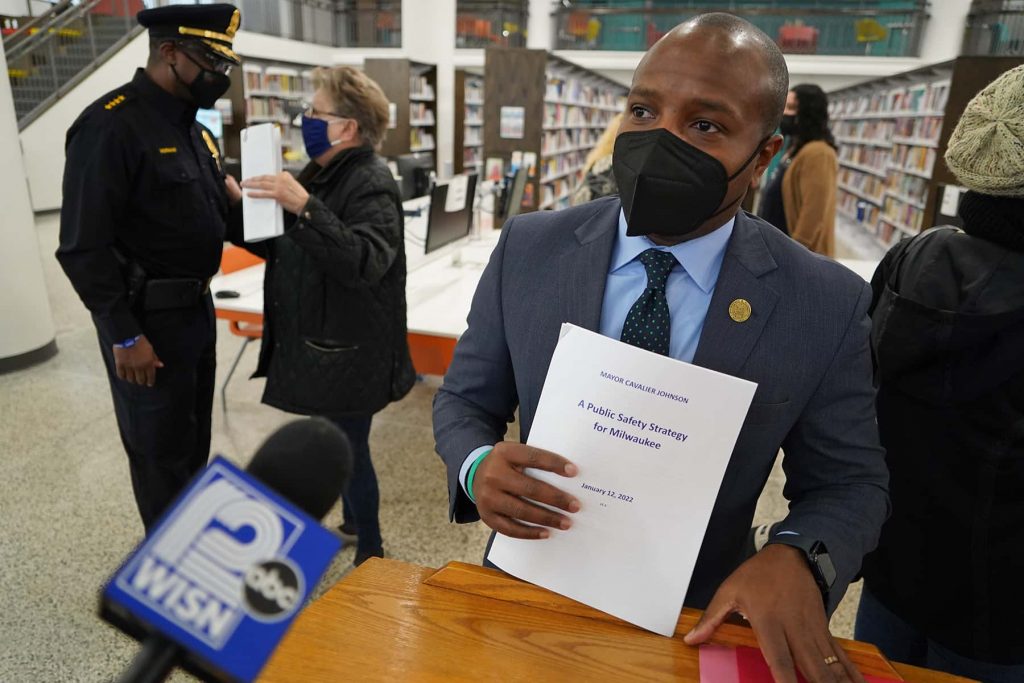

Vos also announced a public website where Wisconsin residents can submit their proposals for district maps, with a deadline of October 15.

Sachin Chheda, director of statewide advocacy group Fair Elections Project, argued Vos opening the process to public input acknowledges a mistake made during the 2011 redistricting process.

“For years, the people of Wisconsin have been demanding transparency and public input into this process, and now even Speaker Vos recognizes how his maps will be seen as illegitimate if he didn’t at least nod to our concerns,” Chheda said via email.

The redistricting commission created by Evers is also accepting maps drawn by the public.

In 2011, Republican aides and a GOP consultant worked from the offices of a private law firm to draw new maps. GOP lawmakers were asked to sign confidentiality agreements before reviewing their new district lines while Democratic lawmakers were shut out of the process.

Republicans have already secured private law firms to work on the next set of maps as well. In April, a circuit court judge voided contracts GOP lawmakers reached with two firms, ruling the Legislature cannot hire its own attorneys for mapmaking until there was a lawsuit pending over the maps.

But the state Supreme Court stayed that ruling in July, pending an appeal from Republicans, thereby allowing Republicans to move forward with the private contracts.

The last time maps were drawn under politically-divided state government, in 2001, the maps ended up going before a federal court appellate court, which re-drew some districts after a long legal battle between Republicans and Democrats.

Lawsuits over the 2020 maps are likely in both state and federal court. In May, the state Supreme Court rejected an effort by Republicans to automatically forward all state-level redistricting lawsuits to the court, bypassing state circuit and appellate courts. However, any state-level lawsuit would likely still end up before the state’s highest court eventually.

Federal lawsuits would begin in district court and could make their way all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. A federal lawsuit related to Wisconsin’s last set of maps made it all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, but was dismissed after a ruling in a similar case.

In April, the first round of 2020 Census numbers released showed Wisconsin’s population has remained mostly steady over the past 10 years, with just a four percent increase. Because of that negligible change, the state will retain the same number of representatives in the U.S. House of Representatives.

On August 13, Democrats filed the first Wisconsin lawsuit related to the 2021 redistricting process, arguing a federal court should step in to draw the state’s next set of political maps because state lawmakers and Governor Evers are unlikely to reach a timely consensus on the matter.

The federal lawsuit came just one day after the U.S. Census Bureau released the data necessary to begin the redistricting process. It argued that the new population numbers show Wisconsin’s current state legislative and congressional districts are vastly out-of-date and that any partisan gridlock and delay in implementing new maps would compromise voters’ constitutional rights.

It contended that the court should immediately take jurisdiction over the mapmaking process and “establish a schedule that will enable the Court to adopt its own plans in the near-certain event that the political branches fail timely to do so.”

“We think there is a high likelihood that there may be an impasse and that the court should be prepared to step in, in the event that that occurs,” said Aria Branch, one of the lawyers in the case.

The new lawsuit was brought on behalf of six Democratic plaintiffs from Dane, Waukesha, and Shawano counties, saying those counties are in state legislative and congressional districts that are now vastly overpopulated, based on the latest Census numbers.

“The census data is very clear that our plaintiffs live in districts that are overpopulated and that if maps are not redrawn before the next election, their constitutional rights will be violated,” Branch said. “They don’t have the same voting power as voters who live in districts that are not overpopulated. Their votes, essentially, count way less than other voters’ (votes).”

According to census data, Wisconsin’s 2nd Congressional District, which is currently represented by Democratic U.S. Representative Mark Pocan, grew the most between the 2010 and 2020 population counts. The district is roughly 7 percent larger than it was 10 years ago, meaning many more voters are packed into the district now than other congressional districts in the state. Under the U.S. Constitution, the population of congressional districts is required to be as equal as possible.

Laurel White

Jeff Miller / UW-Madison