Ex Fabula Fellow Elaine Maly originally shared this story at two events in February. Ex Fabula Fellows tell personal stories to inspire community-led dialogue around some of the most pressing issues in the Greater Milwaukee area — segregation, and economic and racial inequality.

While looking for an old photo to go with a blog I was working on, I came across some letters I’d sent my grandparents from Girl Scout camp almost 50 years ago. Mostly I wrote about the typical stuff. “It’s really cold.” “We went swimming.” “My counselor is really nice.” But there is one letter I can’t get out of my head. The year was 1967. I was 11 years old.

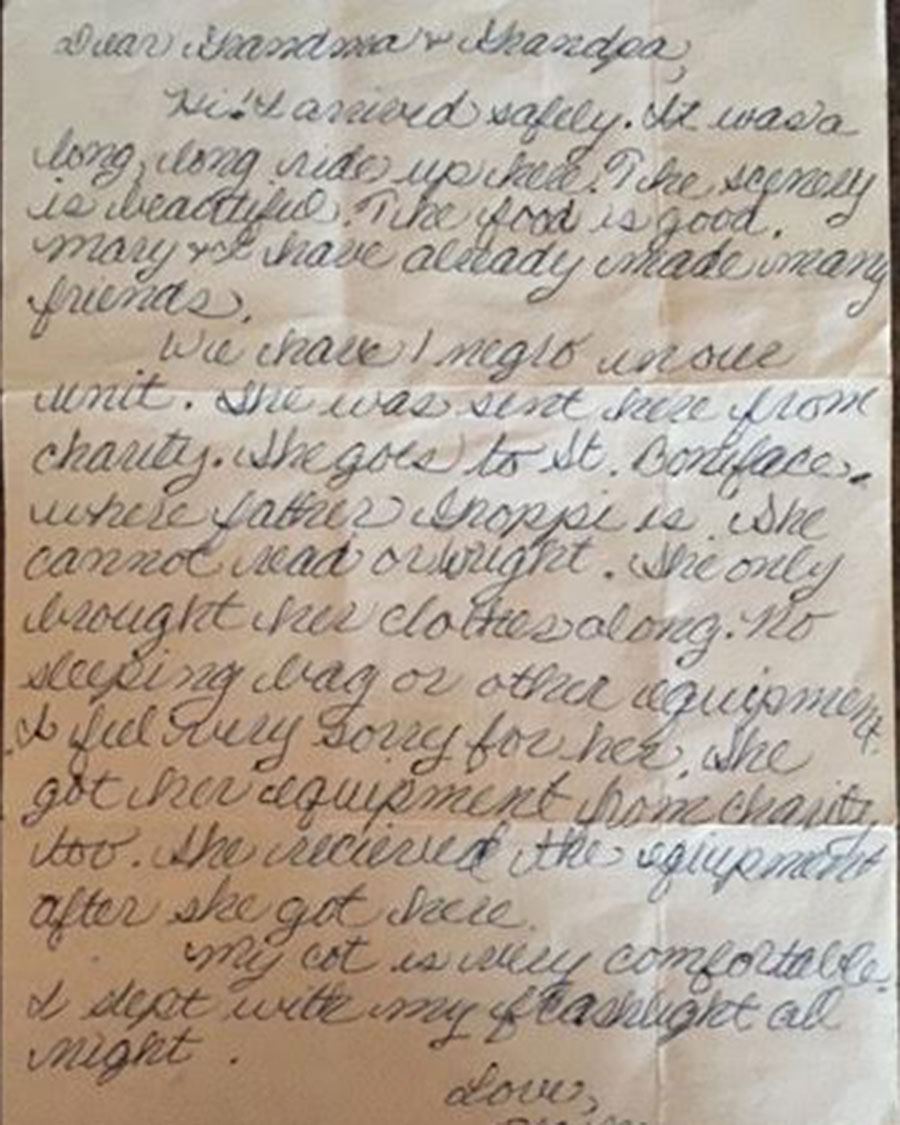

Dear Grandma & Grandpa,

Hi! I arrived safely. It was a long, long ride up here. The scenery is beautiful. The food is good. I have already made many friends.

We have 1 negro in our unit. She was sent here from charity. She goes to St. Boniface where Father Groppi is. She cannot read or wright (sic). She only brought her clothes along. No sleeping bag or other equipment. I feel very sorry for her.

My cot is very comfortable. I slept with my flashlight all night.

Love,

Elaine

I don’t really remember anything about this girl. I don’t remember if I tried to reach out and be friendly or if I kept my distance. I wonder what camp was like for her. Was anyone friendly to her or was she subjected to racial slurs and made fun of? While I was hiking, swimming and singing songs around the campfire, did she find a way to enjoy herself in this strange place with no one who looked like her? Or did she cry herself to sleep in her bunk every night afraid and alone?

And I wonder why I chose to mention this in a letter to my grandparents. They clearly did not want people of color in our neighborhood. This was the summer that the NAACP Youth Group and their advisor, Father James Groppi of St. Boniface Church, were in the midst of their 200 consecutive-day march for fair housing. Around the time that the racial tension erupted into violence, my family was visiting my grandparents miles away from the turmoil. I remember my father asking grandpa what he would do if the turmoil spread to our part of town. My grandpa pointed to the window at the top of the stairs and said that he would get his shotgun out and “pick them off.”

The letter reminded me of this and other times that I witnessed racism as a child. A black gentleman at the shoe store waited on my mother and me when I was about 5. I remember that I couldn’t take my eyes off of him and asked my mother out loud what was the matter with his face. Embarrassed, my mother’s whispered response was, “God just left some people in the oven a little longer.” It made me think of him as sort of a burnt cookie. Like me but somehow imperfect.

Another time, I remember hearing my uncle say that he wouldn’t go to baseball games anymore since they had allowed “negroes” to play.

I think that meeting this girl at camp was the first time I noticed the privilege of being white. I noticed again a few years later when my Girl Scout troop went on a field trip to an inner city school to help teach younger kids to read. Their school was run down and their books were old and damaged. I noticed when a black acquaintance from high school recounted years after graduation how difficult it was for him to attend our predominantly white school. After this conversation, I took out my senior yearbook. I counted eight brown faces in my gigantic Baby Boomer class of almost 1,000. All this time I thought I went to a really diverse school. I noticed when people assumed I was in charge when I was with my African-American colleagues from the Boys & Girls Club.

I didn’t ask to have privilege. It is mine because I was born white. The letter from camp reminds me that my cot has always been very comfortable. I have always had all the equipment I’ve needed. I’ve learned that I have a responsibility to keep the flashlight on, to examine the legacy of racism in my family and the society I live in that values being white over any other color in the rainbow. To speak up. To stand up.

I’ve been telling this story since I found this letter several months ago. After I told it at a Milwaukee Forum event recently, an African-American woman about my age sought me out. She wanted to know which camp I went to. It was the same one she went to and she said that she could be that Negro girl in my story, although the details don’t match up completely. She said that she remembered that there was a white girl at camp who was friendly to her until she got a letter from home telling her about the rioting connected to Groppi and the fair housing march. It was incredible to meet this woman, but what hit me like a ton of bricks on my drive home that night, is that the real demonstration of privilege in this story is that I had no real memory of her. It wasn’t something I carried around. But she never forgot. Never forgot what it was like to be the only black child at camp in the summer of 1967.

Elaine Maly

Originally published on the Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service as Camp memories