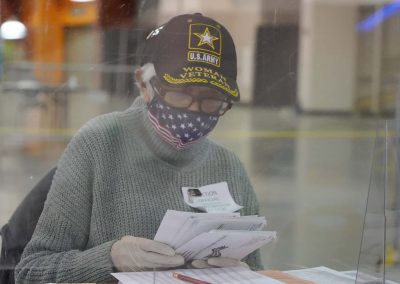

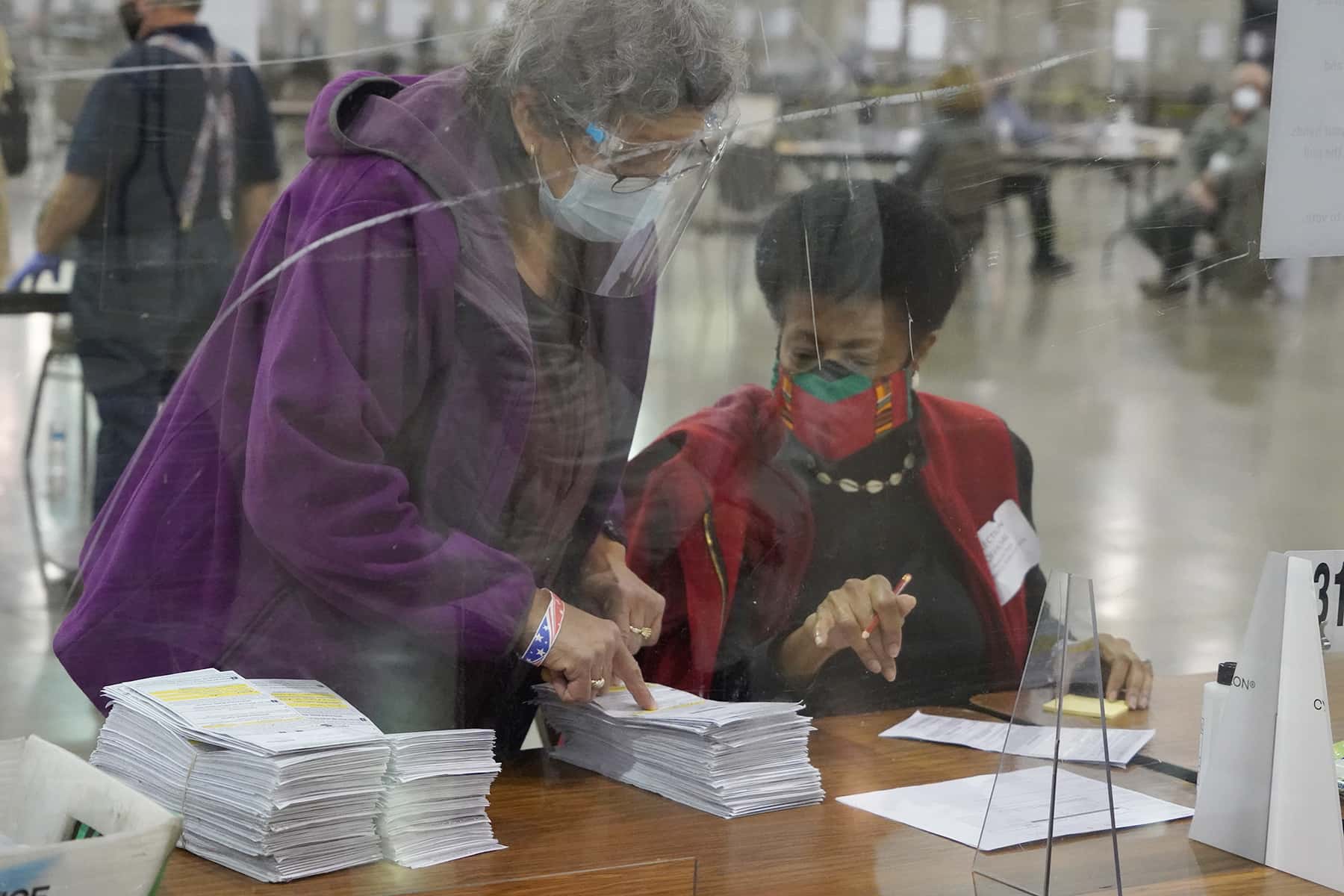

Partisan tensions remain high in Wisconsin as the state begins a partial presidential recount in two counties that helped deliver the state to President-elect Joe Biden.

It is Wisconsin’s second presidential recount in as many elections, but the circumstances in 2020 are far different than they were in 2016, with a sitting president asking for the recount, and the state and national Republican Party apparatus firmly behind him.

Trump’s campaign paid $3 million to conduct the recount in Wisconsin’s Democratic strongholds — Milwaukee and Dane counties — alleging poll workers mishandled absentee ballots despite following advice given to them by the Wisconsin Elections Commission four years ago.

Republican members who sit on the commission suggested at a lengthy meeting on November 18 that the recount is setting up a lawsuit. Despite the rancor, Wisconsin Elections Commission Administrator Meagan Wolfe said she was confident in the process.

“I know that the eyes of the world will be on these two Wisconsin counties for the next two weeks,” Wolfe said. “And we really do remain committed to providing the facts about the process and updates throughout.”

‘Certification’ Of Results

Already, the recount process has raised issues that didn’t come up four years ago, partly because of the experience in other states. In Wayne County, Michigan, home to Detroit, Republican members of the board of canvassers initially blocked certification of election results. They eventually approved them, but later tried to reverse course.

In Wisconsin, state law says the chair of the Elections Commission, who is currently Democrat Ann Jacobs, alone has the power to certify election results once a recount is complete. But Republican commissioner Dean Knudson suggested the full six-member commission might need to give its approval.

“You are not the commission,” Knudon told Jacobs. “It’s clear that that authority statutorily resides with the commission.”

Knudson’s assertion could be significant because the Wisconsin Elections Commission is split 3-3 between Republicans and Democrats, giving either party’s appointees the power to block measures if they stick together.

Asked about Knudson’s comments, Wolfe said that’s not how the process has been handled in the past.

“Over the last 11-plus statewide elections, including the 2016 presidential election, that has been a statutory power of the chair of the commission,” Wolfe said. “So if you look back at who certified any given election over the last four years, it has always been the chair of the commission or their designee. And so that’s my understanding of the process.”

The Wisconsin Elections Commission has a meeting scheduled for Tuesday, December 1, the deadline for the certification of election results.

Indefinitely Confined Voters

Wolfe did not know how many voters could be affected by some of the Trump campaign’s challenges, but the state does keep track of indefinitely confined voters.

Under state law, indefinitely confined voters in Wisconsin can submit an absentee ballot application without providing a copy of a valid ID for voting, like a driver’s license. The commission has said that the “indefinitely confined status is for each individual voter to make based upon their current circumstances.”

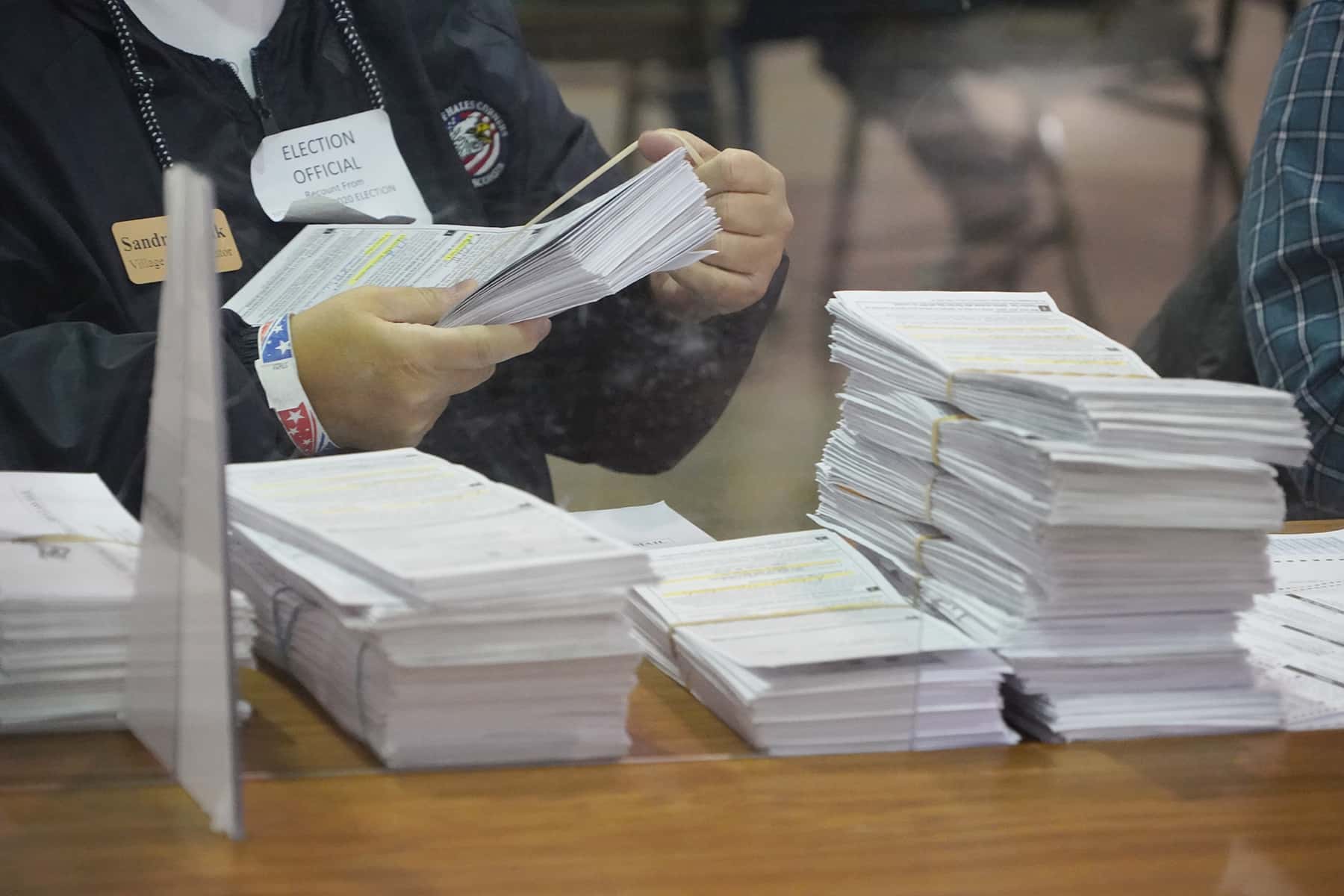

According to statistics kept by the Wisconsin Elections Commission, nearly 216,000 voters said they were indefinitely confined in the 2020 election, up from almost 57,000 in 2016. Those numbers have grown as more people have voted absentee during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In Dane and Milwaukee counties, more than 68,000 voters said they were indefinitely confined in 2020, compared to about 17,000 in 2016. The Trump campaign argues ballots “cast by those claiming to be indefinitely confined who were not in fact indefinitely confined are fraudulent,” but the campaign has not said how it would make that determination.

‘Written’ Applications

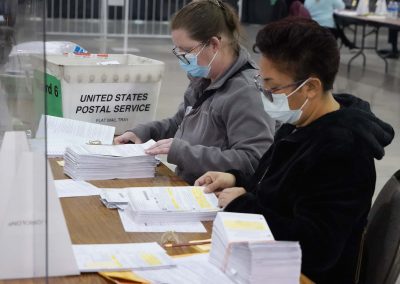

Other pieces of the Trump campaign’s challenge run contrary to advice given by the Wisconsin Elections Commission to clerks throughout Wisconsin. For one, Trump is challenging absentee ballots that did not include a corresponding absentee ballot application, saying that could disqualify “more than 60,000 votes” in Milwaukee alone.

During the meeting November 18, Knudson questioned whether the state’s online portal for requesting absentee ballots could violate the law because it does not specifically include its applications in writing. Speaking to reporters on November 19, Wolfe said she wouldn’t get into the merits of the Trump campaign’s complaint, but she said an electronic record was still a record.

“There’s not going to be a paper record for everything,” Wolfe said. “Many of those records are electronic. They certainly contain words. They’re written, but they’re electronic versions of that request because that’s how the voter chose to make the request.”

Witness Addresses

Trump’s campaign is also challenging absentee ballots that it contends were “illegally altered” by clerks. The dispute boils down to another policy endorsed by the Wisconsin Elections Commission, this one involving the people who witness an absentee ballot being cast.

Under state law, absentee ballot envelopes must include a voter’s signature and address, as well as a witness signature and address. The Wisconsin Elections Commission approved guidance for clerks that allows them to add missing information to absentee ballot envelopes based on “reliable information,” like contacting a voter or referencing government records.

“That’s been in existence since 2016,” Wolfe said Thursday. “It was something that was moved at the time by the Republican members of the commission and has been in place for every election since 2016, including the 2016 presidential election.”

Partisan Tensions Run High

One of the biggest differences between this recount and the one four years ago is that, arguably, the political atmosphere is more confrontational. In 2020, Trump has contended that if “legal votes” are counted, he won the election, a claim that lacks factual evidence.

Trump only asked for the recount in counties Democrats win rather than statewide, which would have cost $7.9 million. Dane County Clerk Scott McDonell told reporters on November 19 that when representatives of the campaigns see potential issues with ballots, they’ll contest them.

“I mean, objections are part of a recount,” he said. “When you notice a recount, that’s what happens on a recount. So, yeah, we’ll get objections. We’ll have to make rulings. That is kind of the whole point of the system.”

The 2016 recount was requested by Green Party presidential candidate Jill Stein, not Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton. By the time it started, prominent Wisconsin Democrats like U.S. Sen. Tammy Baldwin had already started addressing Trump as president-elect.

McDonell said the 2016 process was comparatively harmonious.

“The Trump campaign and the Clinton campaign were helpful,” McDonell said. “I was sending the Trump campaign out to get more sandwiches and stuff, and they were great. I don’t expect that to be the case this cycle.”

Shаwn Jоhnsоn

Lee Matz

Originally published on Wisconsin Public Radio as Wisconsin’s 2020 Recount Bears Little Resemblance To 2016