Significant numbers of Milwaukee voters were dissuaded from voting on April 7 by the sharp reduction in polling places and the threat of the COVID-19 pandemic — with the biggest effects seen among Black voters, according to a new study.

Researchers from the Brennan Center for Justice say their study is the first to measure the impact of the pandemic on voting behavior. The study found that Milwaukee’s decision to close all but five of its 182 polling places reduced voting among non-Black voters in Milwaukee by 8.5 percentage points, and that COVID-19 may have further reduced turnout by 1.4 percentage points. That would mean the overall reduction in turnout among non-Black voters was 9.9 percentage points.

Black voters experienced more severe effects: Poll closures reduced their turnout by an estimated 10.2 percentage points, while other mechanisms — including fear of contracting COVID-19 — lowered turnout by an additional 5.7 percentage points. Those factors combined to depress Black voter turnout by 15.9 percentage points, the researchers estimated.

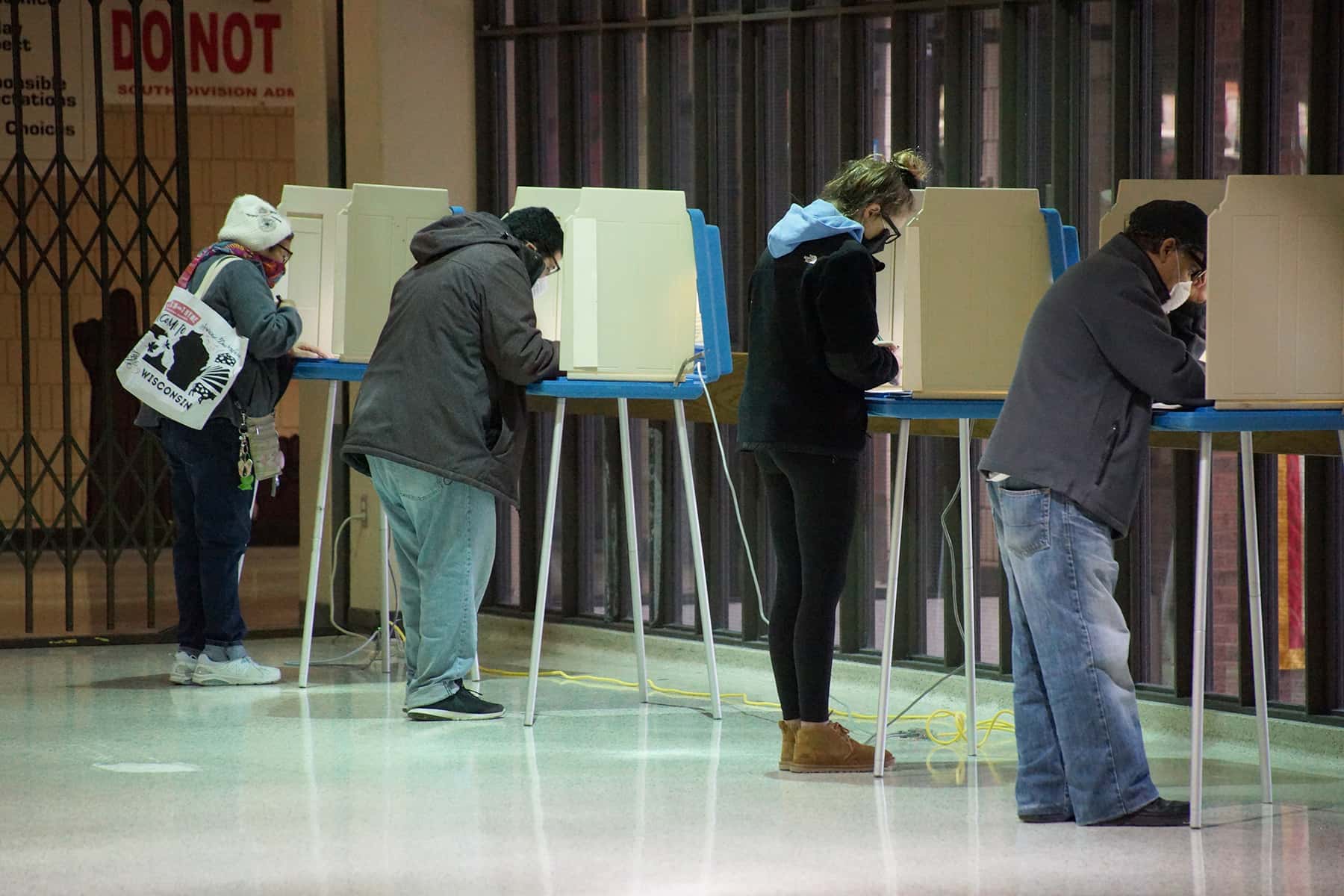

Overall, turnout in the city for the election — which determined a hotly contested Wisconsin Supreme Court race and the state’s Democratic nominee for president — was 32%, according to the Milwaukee Election Commission.

The Brennan Center study raises concerns about disenfranchisement in November, especially among Black residents, as voters choose the president and members of Congress and the Wisconsin Legislature. And it raises fresh doubt about how well states like Wisconsin, which does not have a tradition of widespread absentee balloting, will ensure that all residents can vote in November without exposing themselves to a deadly disease.

The study examined the impact of the city of Milwaukee’s decision to close all but five of its usual polling sites on April 7 due to lack of available poll workers and the effect of conducting a statewide election during a pandemic.

“It is a big effect, and it should make administrators perk up and realize we need to make access to the ballot easier, not harder, this fall,” said researcher Kevin Morris, who conducted the study with fellow researcher Peter Miller for the Brennan Center, a New York University Law School-based center that advocates for changes to improve democracy.

Among those who stayed away from the polls on April 7 was Paula Durrell, a 64-year-old retired breast cancer survivor. The Milwaukee resident told the Milwaukee Neighborhood News Service that the election forced her to choose between her right to vote and protecting her health. She chose the latter.

As an African American resident, “Voting is very important to me,” Durell said. “But it’s not number one right now under the conditions that we’re living in.”

The study compared voters in Milwaukee with those in the rest of Milwaukee County, in Racine County and in the conservative-leaning “WOW” counties of Washington, Ozaukee and Waukesha. The study “genetically” matched each city voter with two similar voters in adjacent areas by party affiliation, gender, household income, education and race/ethnicity.

At the time of the election, those other counties were experiencing COVID-19 infection rates far below the rate of 14 per 10,000 residents in Milwaukee County — the hotspot of infection in Wisconsin. And none of them consolidated polling places as aggressively as did the city of Milwaukee.

Previous studies have shown that closing or moving polling places farther away can depress voter turnout. The report credits fears over the pandemic with even further suppressing the vote on April 7.

“Turnout in Milwaukee was apparently depressed by mechanisms above-and-beyond those explained by polling place consolidation and the voter demographics,” the researchers concluded. “Milwaukee was hard-hit by the COVID-19 crisis; this analysis demonstrates that COVID-19 directly depressed turnout in Milwaukee City.”

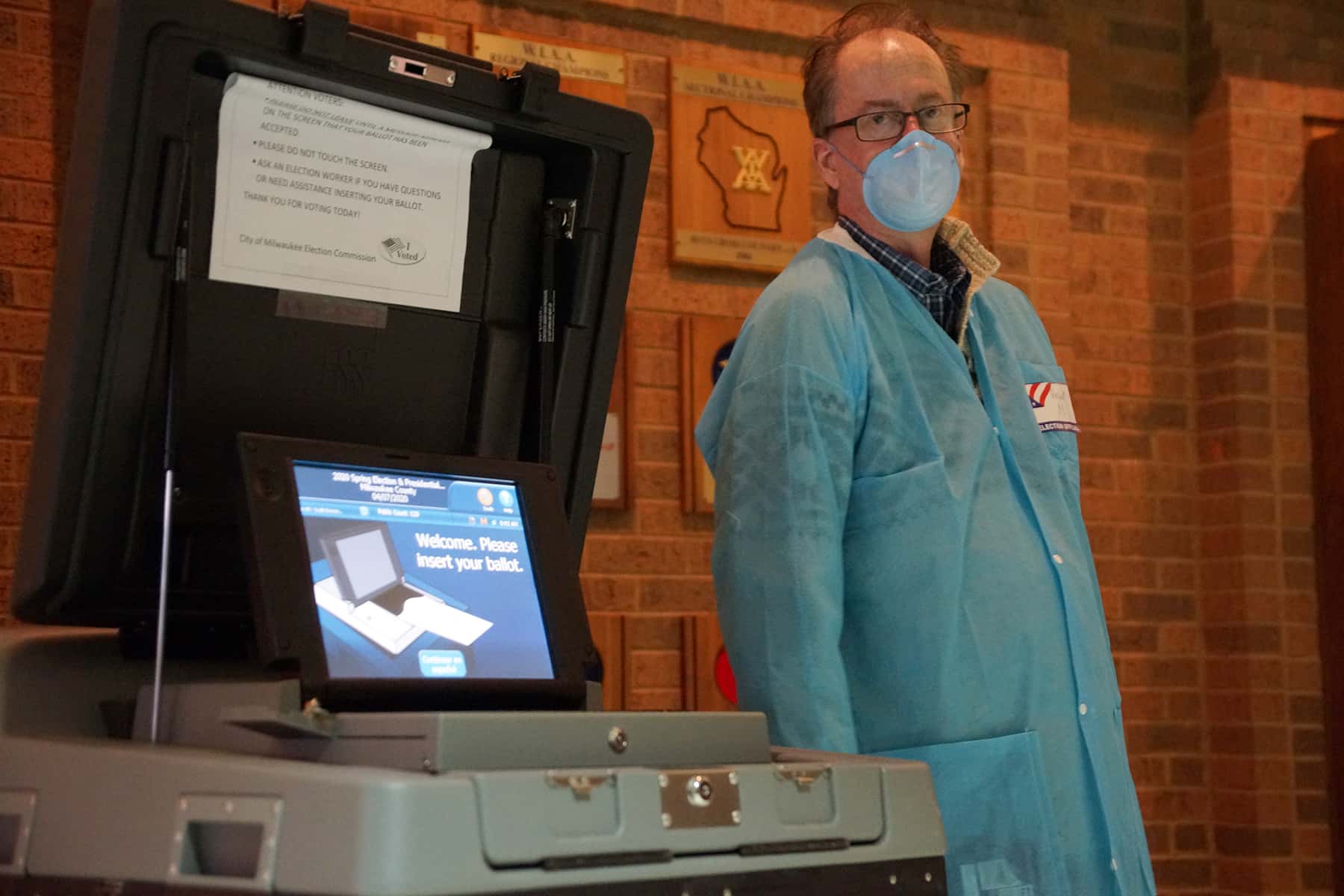

Milwaukee Election Commission Executive Director Neil Albrecht said the city drastically consolidated polling places after the usual election staff of 2,200 was cut to 300 because of the “unparalleled” level of fear of the pandemic. Albrecht blamed the Legislature for pushing ahead with the election, which he said “put the lives of Milwaukee residents at risk.”

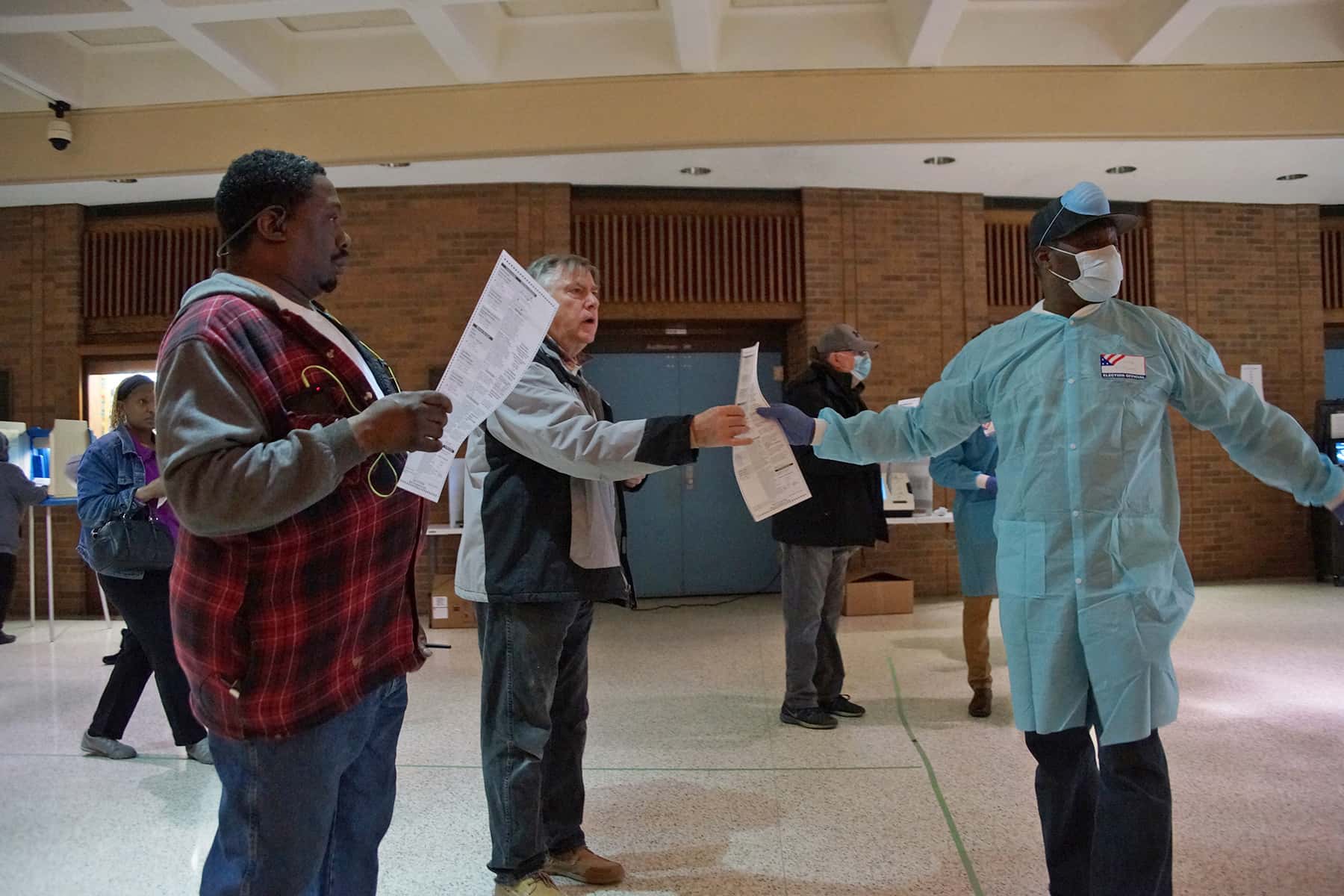

Officials in Milwaukee and around Wisconsin took numerous measures to improve safety at the polls, including using plexiglass barriers, face masks and shields, allowing voters to stay in their vehicles to vote, enforcing social distancing and offering plenty of hand sanitizer.

How the election affected public health is unclear.

The state Department of Health Services found 71 Wisconsites got COVID-19 after voting or working at the polls, the Wisconsin State Journal reported last month. But those people could have been exposed in other ways, health officials said.

The results of outside studies on the issue are mixed. A study by researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh and Ball State University found “a statistically and economically significant association between in-person voting and the spread of COVID-19 two to three weeks after the election.” But a University of Hong Kong and Stanford University study of confirmed COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations found “no detectable surge” in transmission from the election.

Both studies were released before being peer-reviewed.

The Brennan Center researchers said their study raises concerns about racial representation in the November election as voting shifts more to absentee balloting, which is less often used by racial minorities — who studies show are more likely to have their absentee ballots rejected.

A record-smashing 1.1 million-plus absentee ballots were cast statewide on April 7 — four times the amount requested in the previous spring presidential primary in 2016. But that shift did not offset the drop in in-person voting, the researchers found.

Wisconsin Watch found that some voters warily went to the polls after requesting absentee ballots that never came — or decided reluctantly to stay home.

Albrecht said he expects Milwaukee will open most if not all regular voting sites for the Aug. 11 partisan primary and the Nov. 3 general election. Anticipating a large demand for vote by mail, the Wisconsin Elections Commission also plans to send absentee ballot applications to 2.7 million registered voters ahead of the November election.

“Voters will not seamlessly transition to vote by mail,” the Brennan Center researchers cautioned, “and polling place closures this fall will come at the expense of turnout — particularly the turnout of Black Americans.”

Dee J. Hall

Lee Matz, Wes Tank, and Claudio Martinez

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.