For all its political appeal, the concept of black capitalism has, for the past fifty years in Milwaukee and across the nation, failed to reduce inequality or to increase prosperity.

By the time Richard Nixon rode into office in early 1969, the signal achievements of the civil rights movement—the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts and Brown v. Board of Education—were years behind him. In their wake a more radical black movement had gained momentum and had been met with an equally strong white backlash. Indeed Nixon’s victory depended on the creation of a new Republican coalition that felt threatened by the loss of the racial order.

The southern strategy, as it became known, opposed overt forms of race discrimination but rejected any government effort at integration. Using race as a wedge issue without actually talking about race, Nixon associated crime with blackness and promised “law and order.” He signaled his allegiance to white voters who were fearful of blacks without sounding like a racist.

The notion of “black capitalism” was another part of this strategy. During the campaign Nixon coopted Black Power’s rhetoric of economic self-determination to call for a segregated black economy. He used the language of free-market capitalism—a racially neutral and popular idea at the time—to embrace the idea of “black enterprise.” “People in the ghetto,” Nixon said, “have to have more than an equal chance. They should be given a dividend.” Black business and black banking, the theory went, would be the “key to black economic progress” because they would allow black communities to use their own money to create a “beneficial multiplier effect.”

This move allowed Nixon to neutralize black resistance—indeed, to enlist the full-throated support of many activists—while also furthering his coalition’s desire for a diminished social safety net. By discouraging welfare dependency in the name of “black enterprise,” he was able to undermine black demands for economic redress and reparations. “People who own their own homes,” he reasoned, “don’t burn their neighborhoods.” This same logic later justified his dismantling of Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty programs as well as his neglect of other antipoverty efforts, which were seen as costly and responsible for creating dependence on the state.

This strategy highlights Nixon’s mastery of the political sleight of hand. By promoting black capitalism, he was able to accomplish a great deal with very little: he gained business support, lost none of his political base, and spent virtually nothing. The promise of black capitalism was so loosely conceived, it curbed the demands of black separatists and appealed to white voters across the political spectrum. Indeed, in Nixon’s vision, the transformative power of black business would also lead to integration by “build[ing] bridges to human dignity across that gulf that separates black America from white America.”

So great were the political dividends of black capitalism—and at such little cost—that every subsequent administration through Barack Obama’s adopted its edicts and its racially neutral language of “community capitalism,” “enterprise zones,” and “niche banks.” Of all of the components of the southern strategy, black capitalism has perhaps enjoyed the longest life while garnering the least opposition.

But like most things that sound too good to be true, black capitalism has proven to be a mirage. Despite consistent bipartisan support and a seemingly robust infrastructure to support black capitalism, it does not work, either to reduce inequality or to increase prosperity. In fact, considerable evidence suggests that the promotion of black capitalism is far less effective at lifting the black community out of poverty than the conventional progressive New Deal economic programs that it has, by now, all but supplanted. And as far as bridge-building is concerned, the fine print was that that would be the sole responsibility of the black community. With a little federal aid, it placed the “black problem”—the problem of poverty—in the hands of black entrepreneurs to fix unilaterally.

To understand why black capitalism has, for the past fifty years, been perennially both appealing and empty, we must look to its origins in the Nixon administration. As urban violence swept the nation, it was cooked up as a response to the existential crisis confronting the civil rights coalition and the white power structure. Something had to be done to address segregation and concentrated poverty wrought by discrimination, Jim Crow, and state-sanctioned segregation—but what should that something be? Black activists and their allies demanded either reparations or integration, but the white majority vehemently opposed both.

With the vague promises of black capitalism, Nixon took the sting out of the black radicals’ demands, jettisoned Johnson’s antipoverty programs, maintained his opposition to integration, and even won the support of many black leaders. But Nixon’s cynical solution to a specific political impasse turned out to be the perfect package for post–civil rights politics—one that continues to tempt even centrist administrations, since it promises everything while costing virtually nothing. Now as black Americans continue to struggle to recover from the effects of the Great Recession—a catastrophe borne disproportionately by black homeowners, businesses, and banks, for whom there was no bailout—it is worth revisiting this history in the hopes of learning how to steer a better course.

+

If there was any platform that nationalists, militants, integrationists, and moderates could agree on in the late 1960s, it was the imperative of wealth, property ownership, and community economic strength. Across the political spectrum, black groups were putting forward concrete proposals for black entrepreneurship, and each candidate in the 1968 election had a platform plank related to black economic self-determination.

Before his assassination, Robert Kennedy’s community development program had been the most robust and holistic of the lot. It included tax incentives for businesses, Community Development Corporations, job training programs, and government funding for antipoverty programs. Hubert Humphrey, the eventual 1968 Democratic candidate, then took up the mantle, calling his proposal “Black Entrepreneurship: Need and Opportunity for Government Help.” Humphrey’s plans were intended to “enhance black pride and quell black insurgency” and included more funding for businesses through Small Business Administration (SBA) programs initiated by the Johnson administration. He also called for the creation of an “urban development bank” to fund businesses in the ghetto. For Humphrey, black capitalism was one part of his reform package, which included a continuation of the War on Poverty programs.

But the War on Poverty was anathema to Nixon’s strategy. In one of his campaign ads, called “The Wrong Road,” the camera pans across images of poverty-stricken, mostly brown and black faces and a sign that reads, “Government Checks Cashed Here.” In a voiceover, Nixon explains, “For the past five years, we’ve been deluged by government programs for the unemployed, programs for the cities, programs for the poor. And we have reaped from these programs an ugly harvest of frustration, violence, and failure across the land.” Then the music becomes more upbeat, and the camera pans to images of construction sites, a factory line, a shipyard, with Nixon’s voice resonating loud and clear, “We should enlist private enterprise in solving the problems of America.”

In a radio program in April 1968, Nixon doubled down on this messaging, saying that black Americans “do not want more government programs which perpetuate dependency. They don’t want to be a colony in a nation. They want the pride, and the self-respect, and the dignity that can only come if they have an equal chance to own their own homes, to own their own businesses, to be managers and executives as well as workers, to have a piece of the action in the exciting ventures of private enterprise.”

Humphrey pushed back on Nixon’s black capitalism plan in the presidential race, calling it “double talk.” When Nixon promised voters that the program would cost little, Humphrey retorted, “Of course it will take money. Talking about black capitalism without capital is just kiting political checks.”

But while Nixon’s check may have had insufficient funds, Nixon’s double talk paid political dividends, especially since he sold his program as a companion to Black Power. His plan, he assured the public, was in sync with the true spirit of black nationalism: “Black extremists are guaranteed headlines when they shout ‘burn’ or ‘get a gun,’ but much of the black militant talk these days is actually in terms far closer to the doctrines of free enterprise than to those of the welfarist ’30s.” Nixon promised “more black ownership, black pride, black jobs, black opportunity, and yes, black power, in the best, the constructive sense of that often misapplied term.”

Nixon was practically repeating Malcolm X, who had said that the “black man should be focusing his every effort toward building his own business, and decent homes for himself,” although Nixon left out the part where Malcolm had said, “show me a capitalist, I’ll show you a bloodsucker.” He also ignored Black Power’s demands for land, reparations, and political sovereignty. The part Nixon embraced enthusiastically was voluntary segregation, self-reliance, and private enterprise. As Nixon’s speechwriter Raymond K. Price explained, the path forward was to replace “the Negro habit of dependence” with “one of independence” and “personal responsibility.”

Not surprisingly, Republicans embraced black capitalism wholeheartedly. Nelson Rockefeller’s strategist called the concept “a stroke of political genius,” and Rockefeller himself supported the idea. National Review editor William F. Buckley praised the “spirit” of “militant black leaders who have been preaching black initiative, black capitalism, and yes, black power.” Buckley aligned black capitalism with a libertarian small-government philosophy, stating that Black Power was allied with conservatives in their fight against “that huge monster on the banks of the Potomac.” Buckley proposed that the still-undefined program need not involve the entire black populace, because “scattered success can give universal hope.” This was the key objective; the government would not need to underwrite black businesses, just the community’s hope in black businesses.

That hope was also a public relations success. The Wall Street Journal and Time embraced the idea of black capitalism, calling it “thoughtful” and “promising.” Max Ways, the editor of Fortune, wrote that “business is the one important segment of society Negroes today do not regard with bitter disillusionment.” (Nevermind that this likely had much less to do with the black community’s trust in business than their distrust of the government.) And even the New York Times, which usually showed the same disdain for Nixon that Nixon showed for it, endorsed black capitalism, writing that Richard Nixon’s radio speech “on the need for the development of black capitalism and ownership in the ghetto could prove to be more constructive than anything yet said by other presidential candidates on the crisis of the cities.”

The black Chicago Defender, however, was more cautious. Though the paper endorsed black capitalism, it expressed some suspicion over the candidate’s motives, noting that without actual capital, “black power takes on the insignificant aspect of a paper tiger.”

+

Once in the White House, the paper tiger slumped out of its cage. As Nixon’s top aide, John Ehrlichman, explained, “with a relatively small budget impact this is one program which can put the Administration in good light with the Blacks without carrying a severe negative impact on the majority community, as is often the case with civil rights issues.” The budget for Nixon’s black capitalism was small, as was the impact. In fact, black capitalism under the Nixon administration could be said to have been more advertising campaign than policy.

In 1969 President Nixon signed Executive Order 11458, establishing the Office of Minority Business Enterprise (OMBE) within the Department of Commerce. The OMBE was allocated no direct funds, but was instructed to seek private business contributions and help from other federal agencies. What this meant in real terms was that the “OMBE was given responsibility for ‘advising,’ ‘encouraging,’ ‘mobilizing,’ ‘evaluating,’ ‘collecting,’ information and ‘coordinating’ activities,” but beyond this vague mission it did not have a mandate or a budget.

The office’s overseer, Secretary of Commerce Maurice Stans, quickly made clear that the most important objective of the OMBE was to manufacture and broadcast success stories, which would “create pride among the minority which, in turn, creates aspirations of those down the line.” In other words, the program was to be symbolic and propagandistic. “What the black people, the minority people, need more than anything else today is a modern Horatio Alger,” said Stans. “This is the way we will build the pride of these people, and this is the way we will convince the young fellows coming up that they have a chance to do the same thing.” There would be no financial support from the administration for black capitalism.

By 1970 the country was in a recession. Unemployment was so bad by 1971 that the Nixon administration stopped reporting figures. The new aspiring entrepreneurs in the ghetto suffered most acutely as inflation soared and banks closed the credit pipeline. A black accounting firm in New York summed up the situation facing new black enterprises, noting that “the people least likely to succeed in business were trying to make it at a time when seasoned businessmen were having trouble.”

Small businesses were the most vulnerable and least likely to succeed in this environment, yet all the OMBE programs were geared toward creating more small businesses. This focus was in part due to the lack of funds to support large businesses, as well as the fact that the program was more about business myth-making and platitudes of racial pride than it was an outcome-oriented effort to help the black community accumulate business power.

Small businesses were supposedly the lifeblood of entrepreneurship, and this may have been true at some point in time; but small business was no way to grow wealth in the 1970s. Large multinational firms were making more profits and using economies of scale to reduce costs, and they were already squeezing out small businesses, a trend that was only just beginning. As Walmart was building its profitable empire, blacks were being told that to prosper, they should focus small and local.

In 1969 Section 8(a) of the Small Business Act authorized the SBA to manage a program to coordinate government agencies in allocating a certain number of contracts to minority small businesses—referred to as procurements or contract “set-asides.” Daniel Moynihan, author of the controversial Moynihan Report, helped shape the program. By 1971 the SBA had allocated $66 million in federal contracts to minority firms, making it the most robust federal aid to minority businesses. Still, the total contracts given to minority firms amounted to only .1 percent of the $76 billion in total federal government contracts that year.

Yet even these miniscule minority set-asides immediately faced backlash from blue-collar workers, white construction firms, and conservatives, who called them “preferential treatment” for minorities. Ironically, multiple studies revealed that 20 percent of these already meager set-asides ended up going to white-owned firms, which led to a 1973 amendment that stated specifically that the businesses had to be owned by minorities. Unsurprisingly, it was also revealed that Nixon had used these set-asides to bestow political favors.

The least controversial and most durable black capitalism program was the 1969 Minority Bank Deposit Program (MBDP). Ever since Washington policymakers had linked ghetto rioting with credit exploitation, multiple programs had been proposed to fix credit inequalities. They ranged from creating new banking institutions to providing loan guarantees, capital infusions, or Marshall Plans for the ghetto. Rejecting all of these proposals, the Nixon administration’s program simply asked government agencies to deposit their accounts in black banks—banks that were not only owned by blacks, but which actively sought to provide financial services to the black community.

In 1968, when William Proxmire’s Senate Banking Committee had discussed whether agency deposits might help bolster black banks, a representative black banker remarked that these agency deposits would not provide a good basis for financing banks in the ghetto because they were too unstable. No matter. The program cost nothing. The initial goal was to encourage federal agencies to deposit $100 million of their accounts in black banks; the actual yield was about $35 million by 1971.

The first agency to volunteer was the Post Office, which announced that it would be depositing $75 million in black banks. It would actually deposit only about $150,000. And even this small sum was rotated through several different banks. One businessman quipped, “It was like me saying I’ll lend you $365,000 for the next year and then lending you a dollar every morning and taking it back every night.” These were not the deposits that black banks needed—they were the same type that had been crippling them for years.

The president of Unity Bank in Boston complained that the Post Office refused even to bring the money to the bank. “They expected us to hire a security service to collect deposits that we couldn’t even make any money on.” After complaints about the added cost burden of the postal deposits, the program promised the banks that they would send them more valuable deposits from other agencies. While this did happen, in the end the government deposits cost the banks more than they were worth.

An enduring legacy of the Nixon administration’s black capitalism program is affirmative action, which was initiated by the Equal Employment Opportunity Office (EEOC) with the aim of encouraging companies to hire more black employees. The 1969 Philadelphia Plan required construction companies that had federal contracts to set numerical goals for hiring blacks. The word “quotas” brought a quick backlash from employers and blue-collar unions, so Nixon withdrew the demand and asked businesses to set voluntary hiring goals. Striking a political compromise, the EEOC began measuring and keeping track of these “voluntary goals.” It did this across a variety of businesses that had government contracts, and it encouraged other businesses to prioritize hiring minorities.

In supporting affirmative action, Nixon claimed that “jobs are more important to the Negroes than anything else.” This was obviously not true, but while asking businesses to provide jobs was not politically popular, it was an acceptable compromise in a politically fraught climate. Nobody lobbied for affirmative action, and no one had demanded it. It was a weak compromise position meant to throw a bone to the black middle class and deal with black militants without spending too much politically or financially.

According to historian John David Skrentny, “Affirmative action was legitimated very quickly, in a matter of a few years, in a very turbulent time, and by a variety of people pursuing very different goals.” Affirmative action would be fiercely attacked by Nixon’s own Republican Party until it was almost fully dismantled. It was more vulnerable than black capitalism because it cost whites more, and it would become the epicenter—which it remains—of a white backlash that claimed it was “reverse discrimination.”

+

All the black capitalism programs, including affirmative action, relied primarily on the voluntary participation of private firms and government agencies. The Nixon administration asked large companies and banks to help alleviate ghetto poverty by increasing minority franchise opportunities, investing in minority businesses, and lending to minority businesses. With weak incentives, few complied. Even the conservative Wall Street Journal reported in 1970 on the “stillborn” business volunteer program.

In 1970 the Harvard Business Review surveyed the top 500 industrial corporations and business leaders about their participation in black capitalism programs; it found that only a handful of executives had made any financial contribution to black businesses. The executives believed that there was not enough financial incentive to participate. Most revealing in the survey was the report’s finding that “whatever may be said in public, it is clear from many private conversations that most of the existing efforts by white corporate executives to assist black business came about as a result of fear engendered by the ghetto riots, threats, and pressures from militants, and to some extent pressure of influence from government officials.” With only fear as a motivation to help, the researchers concluded that “we cannot leave the promotion of corporate involvement in developing minority business solely to the conscience and moral views of corporate executives.”

Though few businesses volunteered, that is not the impression the public received. Several corporations, including AT&T and Coors, took out series of long-form advertisements to promote all the ways in which they were helping black business. General Motors’ president, James Roche, served on Nixon’s advisory council and publicly promoted black capitalism initiatives, stating that it was the responsibility of businessmen “who have worked within and gained from the free enterprise system, to help others share in it. It is us, who must cherish the freedom in free enterprise, to assure that it is freely open to everyone.” (General Motors had indeed gained from free enterprise, but they had also gained from $4 billion in federal defense contracts over the prior 10 years.)

Despite such advertisements, most of these companies put up little or no money at all. Perhaps this was because of the slow economy. According to Undersecretary of Commerce Rocco C. Siciliano, “It’s hard to imbue businessmen with social consciousness when business is bad.” In 1970 Whitney Young lamented, “I remember listening to the head of a major corporation brag about all his firm was doing. After some close questioning, I found the sum total of these grand efforts added up to less than two dozen summer jobs for black youths in only three of the sixty cities in which that company operates.”

In 1969 Young had proposed a National Economic Development Bank that would look like a cross between the Federal Reserve and the World Bank, with regional offices across the country to help black communities finance community self-help projects. He was a committed advocate of black self-sufficiency until he met his untimely death in 1971 in Nigeria. His last printed words appeared in the New York Times three days after his death. They were words of disappointment. He called corporate America’s engagement with black capitalism the “great copout.” He blasted the business community for being dilettantes, first flirting with civil rights and then quickly moving on to other “causes.” He said that “the period of corporate activism in social concerns [1967–69] coincided with two phenomena of great importance—a booming economy and the spread of urban rioting.” Young said of the corporate executive, “when he’s trying to help solve social problems four hundred years in the making, created by the racialist attitudes of companies and unions like his own, he suddenly expects fast returns and instant successes.”

If there were no fast returns for corporations or for the black community, Nixon did reap a fast and instant result from black capitalism. The biggest win for his administration was that black capitalism turned out to be a very effective antidote to militant black uprisings. Nixon and his FBI had targeted the Black Panthers as enemies of the state. “The Black Panther party, without question, represents the greatest threat to the internal security of this country,” said J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover had sent FBI agents to infiltrate the Panthers’ ranks and subvert their organization. Panthers were imprisoned, harassed, and even killed by the administration in showdown after showdown. Party leaders such as Huey Newton and Eldridge Cleaver led the movement at its height from prison and from exile in Cuba, respectively.

However, the Panthers as an organization was ultimately killed not by force, but by a slow drying up of funds and supporters due both to a change in the environment and to a subtle subversion of its cause by Nixon. First, the Vietnam War abated and the draft diminished, so the Panthers lost support from white student protesters who no longer had a shared colonizer to fight. The other base of their support was a large part of the black community—the moderates. This group was neutralized by superficial concessions from the administration. The concessions were black capitalism and affirmative action.

The movement’s leaders themselves were divided over the lure of black capitalism. In the early 1970s, the Black Panthers’ newsletter urged blacks to “support the businesses that support our community.” A revolution having been thwarted, the Panthers put aside talk about “capitalist bloodsuckers” and moved toward a more “pragmatic” approach of small black businesses. According to noted black sociologist Robert Staples, “one of the most curious turnabouts was the Panthers’ embrace of Black Capitalism.”

Cleaver split with Newton and Bobby Seale and maintained an anti-capitalist stance. He wrote Stokely Carmichael, who had recently stepped down from Panthers leadership, an open letter in 1969 calling him out for providing the Nixon administration with a potent weapon against the black community. Black capitalism was just a continuation of black exploitation, according to Cleaver. He said that Carmichael had surrendered Black Power to the Nixon administration to be corrupted into black capitalism, thereby rendering the term and the movement powerless. “It has been precisely your nebulous enunciation of Black Power,” he scolded Carmichael, “that has provided the power structure with its new weapon against our people.”

Cleaver had hit on a tension in the Black Power philosophy: was it possible to derive black power as a concession from the white power structure, or could the movement’s aims only be achieved through complete political sovereignty brought about by revolution against that power structure? The genesis of the Black Power ethos was a natural enough response to white oppression, a rebuttal to white power, but would white power have to be defeated to achieve black power, or would half measures do? For the Panthers, the objective had always been political independence, but at least part of the movement was persuaded that black power could be achieved through economic success. This is what black capitalism was proposing.

The theory behind developing a separate black economy had been that economic power would lead to political power, but perhaps they had it backward. If the rollout of the black capitalism program had demonstrated anything, it was that economic power could not be achieved without government help. American businesses, banks, and homeowners had all benefited from being inside the power structure and receiving its bounty. Blacks had been on the outside, and their lack of political control translated into a lack of economic power.

Until black people could access the levers of political power, they could not unleash government or business support, both of which were essential for economic success. In fact, the only reason the government or corporations had contributed anything at all to growing black businesses had been as a reaction to the threat of violence that the Panthers and militants had created. The initial Black Panthers movement had held a modicum of power, even if it was derived from fear. But this fear was the reason the business community and the federal government had focused on black ownership in the first place. The black capitalism program and its reliance on the white power structure removed this source of power.

It also deprived the black community of another important source of power derived from collective action. By dividing the community between the entrepreneurs and the masses of consumers, the black community was placed at cross-purpose. By linking large white corporations with aspiring black businessmen, the race cohesion—that rage the Panthers had channeled and amplified—was dissipated. This, in turn, removed the incentive for businesses to participate in black capitalism. Black capitalism also cannibalized the budget of the War on Poverty—the budget of Johnson’s Office of Equal Opportunity was successively cut and siphoned off to OMBE programs. The War on Poverty, which was designed to help the poor of all races, was instead being diverted to help aspiring black entrepreneurs, isolating the black community from yet another source of strength: the interracial collective action of the poor.

An expert in political détente, Nixon used black capitalism to drain just enough rage from the poverty-stricken ghetto to deflate the revolution. Ultimately, black capitalism was anemic and utterly unresponsive to the needs of the black community. Eventually, bankers and entrepreneurs did find a way to profit from black communities—through subprime loans. The 2008 financial crisis decimated black communities, devouring over 50 percent of their wealth through foreclosure and bankruptcy. Just as black communities were hit harder than white ones, the black banking industry was crushed by the crisis. Over half of black banks failed during the crisis and the remaining industry continues to struggle to overcome the headwinds of segregation and concentrated poverty. In the 50 years since the monumental victories of civil rights, the wealth gap has turned into a wealth chasm.

When the Emancipation Proclamation was signed in 1863, the black community owned a total of .5 percent of the total wealth in the United States. More than 150 years later, that number has barely budged: blacks still only own less than 2 percent of the wealth in the United States. When Martin Luther King, Jr., stood on the steps of the Washington Monument in 1963, he declared, “America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’” The funds are still insufficient.

The past 150 years have yielded next to nothing in terms of wealth creation for black America, and any economic policies designed for the creation of black wealth should be seen as nothing other than absolute failures. Whether the next 150 years yields a different result will depend, in part, on understanding the nature of that failure.

Boston Review

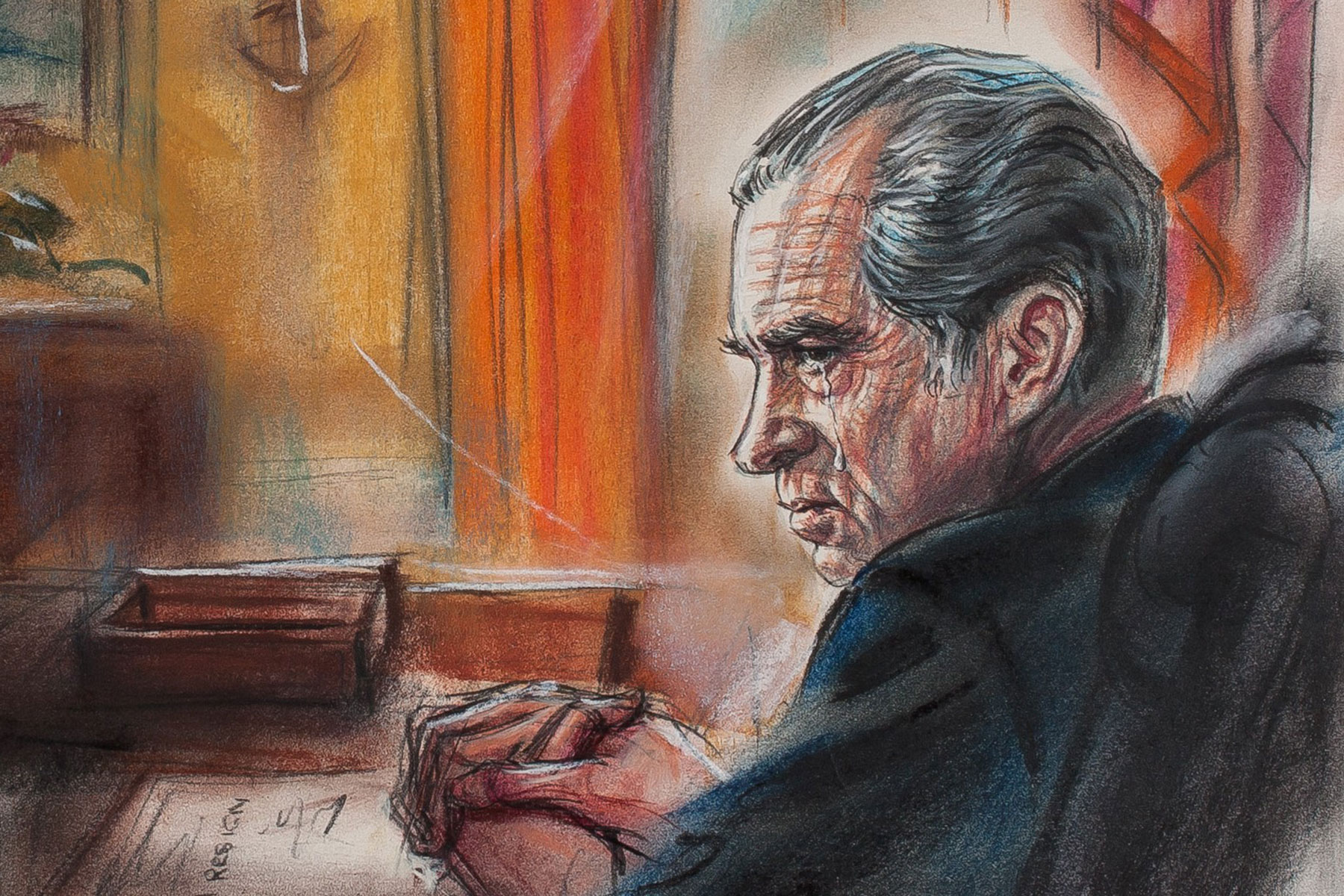

Richard Nixon Presidential Library

Freda Reiter, courtesy of online Gallery 98

Originally published on the Boston Review as A Bad Check for Black America