The 1861 Milwaukee Bank Riot was one of those moments that people thought would never be forgotten. Now, there are few remaining articles and references to this flashpoint in city history.

The riot was about much more than that single day of chaos on June 24, 1861. To understand full story requires going back a few decades to the presidency of Andrew Jackson. In 1836, President Jackson’s war on banks culminated in one of his final acts: vetoing the reauthorization of the Second Bank of the United States — the only nationally chartered bank at that time. Along with his Specie Circular Executive Order, IT created a shortage of stable currency.

“There was a major financial panic. It’s called the Panic of 1837, where a lot of banks failed in the country and we had a recession, depression,” explained banking historian, Richard Sylla.

The Panic could not have come at a worse time for the newly founded Wisconsin Territory, which split from the Michigan territory just a year earlier. Archivist Kevin Abing, from the Milwaukee County Historical Society, says it had a huge impact on the fledgling frontier.

“A lot of banks went under across the country, credit shriveled up for the large part. It just brought any commerce or land speculating to a halt. That was definitely the case here in Milwaukee,” said Abing.

But the war on banks and the resulting Panic did more than just cripple the economy, it created a great distrust in banking itself. When Wisconsin finally became a state in 1848, banking was prohibited by its constitution, which meant the state would not charter any banks.

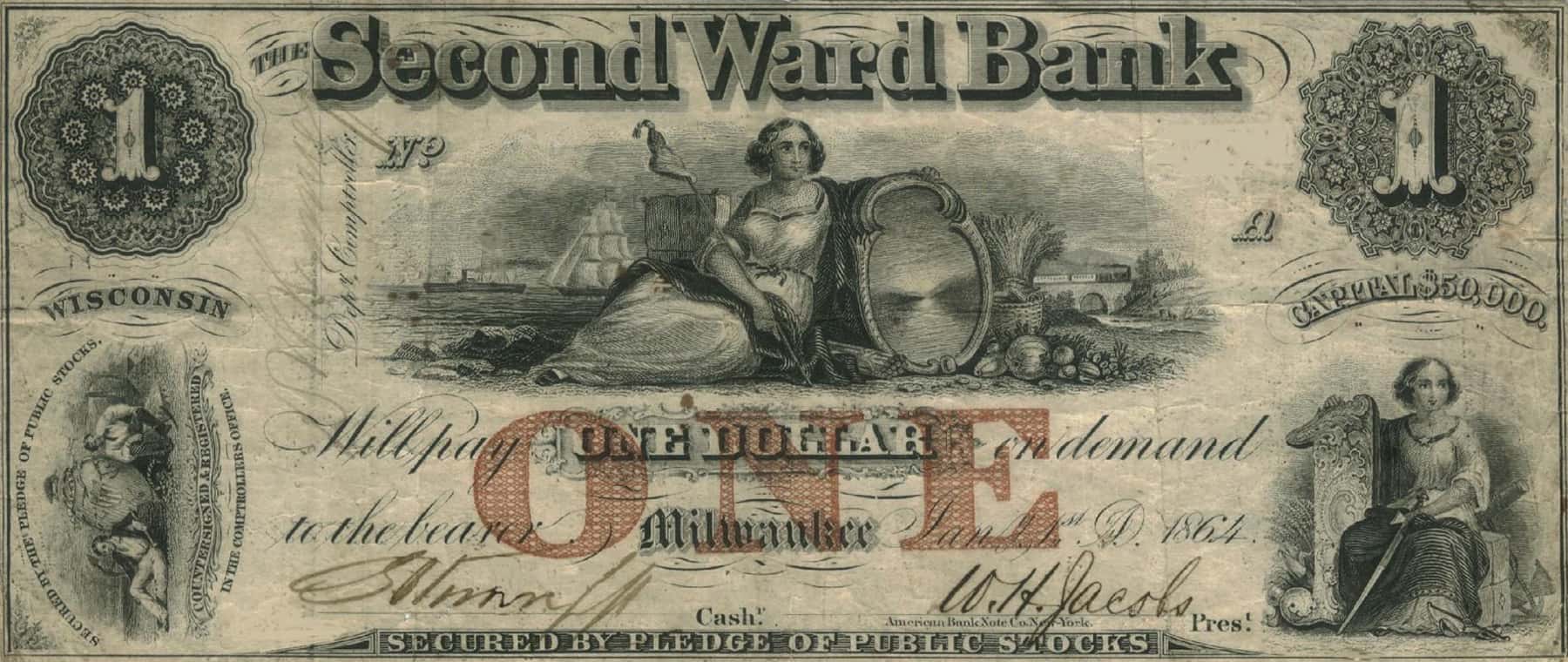

Since there was no central financial institution in the U.S. or standard currency, no charters theoretically meant no banknotes. At that time, a banknote was similar to the $1, $5 bills we have today.

“Now, banknotes are issued by the United States government,” said Sylla. “But before the Civil War in the United States, there were some hundreds of banks and each one of them issued banknotes like the currency we have in our pockets now. But these were obligations not of the United States government, but of the bank itself.”

Worthless Banknotes

Notes being the obligation of the bank issuing them was really important to the story of the 1861 Milwaukee Bank Riot. Despite the lack of charters, there were still banknotes circulating in Wisconsin. That was due in part to a couple of Scotsmen, George Smith and Alexander Mitchell, who would go on to found Mitchell’s Bank when banking was made legal in Wisconsin just a few years later. Each institution was responsible for insuring their assets through bonds. By 1861, when southern states seceded and the Civil War began, three-quarters of Wisconsin banks were backed by southern bonds.

“The southern governments that issued the bonds were unlikely to want to payback the bonds that were held outside their country, like in Wisconsin,” added Sylla. “So you walked into a bar in Milwaukee, and you try to buy your beer and the bartender would say, ‘The banker told us not to accept your money.’ So if you got paid in that money a few days before, you might have been quite angry.”

The Wisconsin Bankers’ Association met to discredit dozens of banks, making their notes worthless. But by June 1861, the banks were still in a free-fall. On Friday, June 21, the Association discredited 10 additional banks. News of this came down the next day, after many of Milwaukee’s German laborers were paid with the now worthless banknotes.

The following Monday, hundreds of working men marched down the streets of Milwaukee, ending up at the doors of Mitchell’s bank. Alexander Mitchell tried to calm the crowd, but retreated after one of the rioters threw a stone that narrowly missed his head. The mob then went crazy.

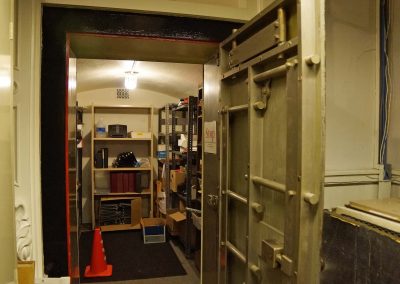

“They started busting windows and breaking doors and eventually they broke through the doors of Mitchell’s bank and they ransacked the place,” said Abing. “Mitchell was smart enough to lock the money all up in the vault, so that was safe. But pretty much anything else that was left in the building was trashed — all the furniture, a lot of bank records and things were lost. The furniture was thrown out into the street and eventually they started a big bon fire with it all.”

The mob repeated the process at the State Bank across the street and threw stones at the nearby Bank of Milwaukee and Juneau Bank, as well as the Newhall House Hotel. The riot continued until a local militia was deployed to restore order. Martial law was declared by the Wisconsin governor and in the end no one was gravely injured, although according to the New York Times, the mob did stone the mayor. He was slightly injured.

The bankers eventually agreed to pay the workers for their discredited banknotes, calming the city down for a while. Two years later, the National Currency Act of 1863 was signed into law, creating currency backed by U.S. government bonds. It was the beginning of the end for bank-issued currency and the start of our current system of banking.

The State Bank building merged with the Bank of Milwaukee building in the early 1900s. It is now the oldest commercial building in Milwaukee. It is now known as the Grand Avenue Club, and there are few signs of its former life, aside from some old bank vaults which have since been transformed into storage closets.

Jоy Pоwеrs

Lee Matz and Milwaukee County Historical Society

Originally published on Wisconsin Public Radio as The 1861 Bank Riot That Rocked Milwaukee

Wisconsin Public Radio (WPR) is a civic and cultural resource that exists to enlighten and enrich the quality of life for its listeners. Help support their mission with a contribution.