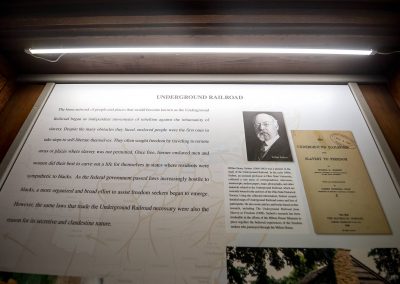

As enslaved people sought freedom in Canada in the mid-1800s, some passed through Wisconsin on the Underground Railroad. The secretive nature of the operation makes it difficult for historians to fully track, but existing records show how Wisconsinites lent a helping hand to those fleeing slavery in the South.

The state has one remaining authenticated stop along the path to freedom that is preserved and open to the public. The Milton House, about 35 miles southeast of Madison, is the state’s shining example of the lengths Wisconsin abolitionists went to hide, protect and transport people who were once property.

The town of Milton’s founder, Joseph Goodrich, built Milton House as a stagecoach inn in 1844. Its location along prominent travel routes brought plenty of traffic, which served as effective cover for the Underground Railroad.

“We think that freedom seekers would have been put on a wagon and put underneath supplies for the hotel,” said Keighton Klos, executive director of Milton House. “They’d be brought to the cabin, and you’d unload all of those supplies along with the freedom seekers.”

Goodrich built an underground tunnel between the back cabin and the inn so fugitives could enter in secrecy. As a Seventh-Day Baptist, he held strong anti-slavery beliefs that motivated his operation.

“A lot of the people in the town with him were also of that faith,” Klos said. “We do believe that a lot of people in town knew what he was doing and were actively helping him run his Underground Railroad stop, which was not necessarily the norm at other underground railroad sites.”

Klos said Andrew Pratt is the only enslaved man they know of by name to have come through Milton House, but historians believe a few hundred freedom seekers passed through Wisconsin as a whole.

Milton was not the only town where residents took the abolition movement into their own hands. Wisconsin Black Historical Society/Museum founding director Clayborn Benson said the state had two main corridors of travel for those escaping slavery, up through Milton and central Wisconsin, or to the east along Lake Michigan.

Milwaukee and Racine counties are home to a handful of historic abolitionist sites, and the path to freedom continued up through Green Bay.

Most notable was the story of Joshua Glover, a freedom seeker who came to Racine and lived there for two years before his enslaver found him and had him thrown in jail in Milwaukee. Benson said it made national news when a crowd of hundreds protested and broke Glover out of jail, setting him on a path toward true freedom in Canada.

“Other states did it, too, but they snuck it. They did it when it wasn’t popular, at nighttime and when the soldiers were gone,” Benson said. “Wisconsin wanted to make a statement, and that was clearly an abolitionist statement that the federal government was not going to tell them what to do.”

That statement lives on in a historical marker in Milwaukee’s Cathedral Square Park and in the walls of the Milton House, where the stories of freedom seekers and the Wisconsinites who helped them are passed on from generation to generation.

Lorin Cox

Milton House Museum and Аngеlа Mаjоr

Originally published on Wisconsin Public Radio as Seeking freedom: Wisconsin’s role in the Underground Railroad and abolitionist movement