By Joshua Holzer, Assistant Professor of Political Science, Westminster College

The United States is the only democracy in the world where a presidential candidate can get the most popular votes and still lose the election. Thanks to the Electoral College, that has happened five times in the country’s history, including in 2000 and 2016.

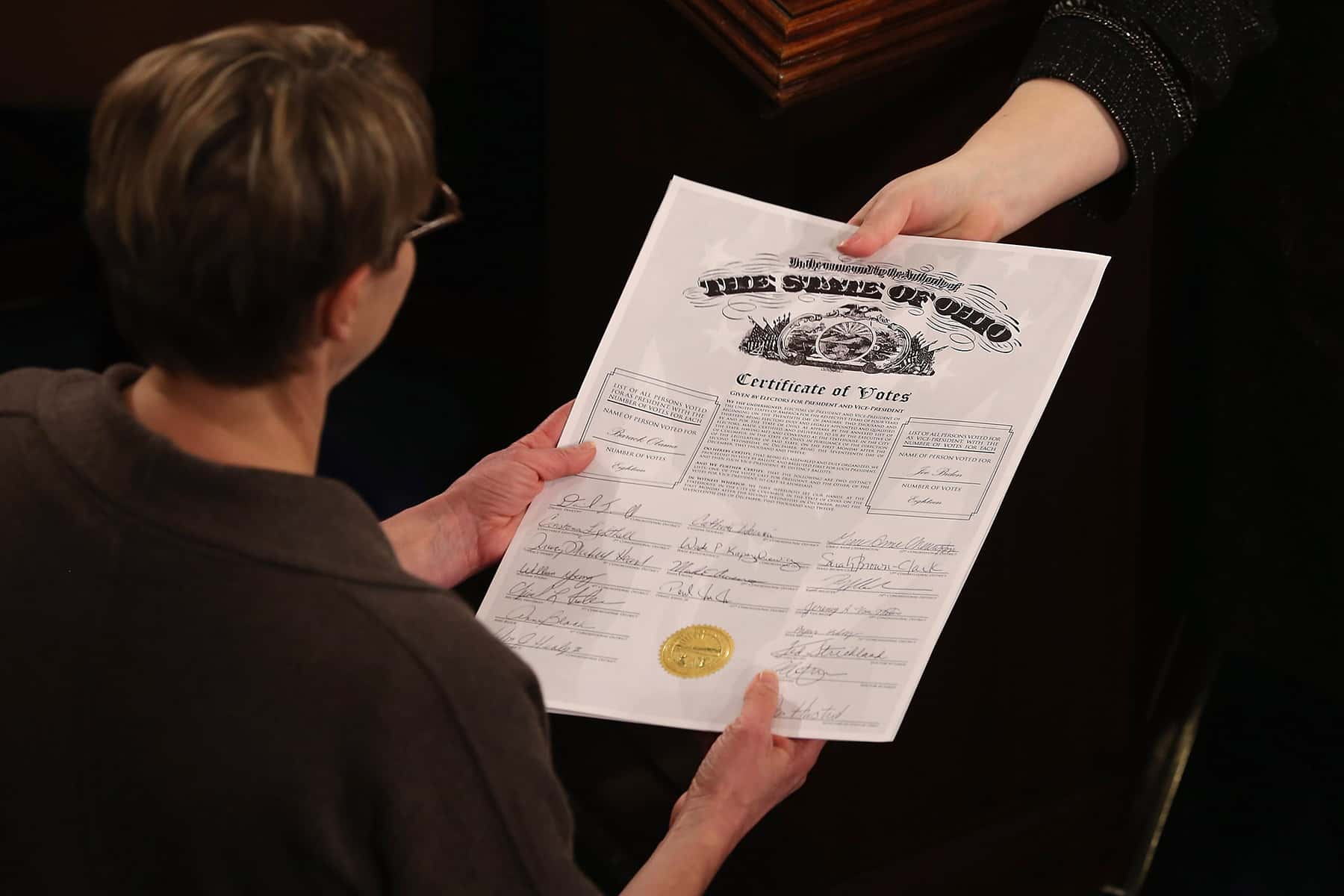

Rather than totaling up how many people vote for each candidate nationwide and declaring a winner, the U.S. assigns each state a number of electoral votes based on how many representatives and senators are sent to Congress. Washington, D.C. gets three. In D.C. and 48 states, those electoral votes are assigned to the presidential candidate who wins that state’s popular vote. In Maine and Nebraska, candidates earn two electoral votes for a statewide win, plus one more for each congressional district they win in.

This system gives voters in states with smaller populations more influence than voters in larger states – assuming everyone turns out to cast a ballot. The result is that different candidates can – and do – win the popular vote and the electoral vote. As a scholar of presidential democracies around the world, I have examined a range of options the U.S. could consider, if it chose to change how the president is elected. My own research has found better human rights protections in countries that elect presidents who are supported by a majority of voters – which is something U.S. Electoral College does not guarantee.

Plurality voting

A common method of electing a president is plurality voting, used in Mexico, South Korea, the Philippines and other countries. It is also already widely used across the U.S. for electing people to offices other than the presidency. Using this method, whichever candidate has the most votes after a single round wins. Plurality voting has the benefit of simplicity. One problem arises, however, when there are several people running for president. If the vote is split too many ways, the overall winner may not actually be very popular.

For example, in Chile, Salvador Allende won the 1970 presidential election with only 36.3% of the vote. In other words, more people voted for his opponents than voted for him. Allende’s policies led to economic problems, public protests and eventually a U.S.-backed coup. This democratic breakdown ultimately resulted in a brutal 17-year military dictatorship.

Runoff voting

Another method of electing a president is runoff voting, in which there are potentially two rounds of voting. If someone wins more than half the votes in the first round, that candidate is declared the winner. If not, the two candidates with the most first-round votes face off in a second round of voting. In 1962, France adopted runoff voting for presidential elections. A variation of this rule is now used in many countries around the world, particularly former French colonies.

Runoff voting prevents less-popular candidates from securing the presidency with only a narrow sliver of support. As such, runoff voting is popular among countries seeking to avoid the “Allende syndrome” – which is when a president is elected with a narrow plurality, and then the country descends into a military dictatorship. Indeed, upon Chile’s return to democracy in 1990, the country adopted runoff voting so that future presidents would need to obtain at least a majority of support.

In order to win under runoff voting, candidates need to be broadly popular. That’s because they need to win enough of the overall vote in the first round to advance, and then they need to win more than half of the second-round votes. As a result of that wide support, the eventual winners are often more likely to be responsive to the concerns of a broader segment of the population. In my own research, I find that presidents elected by runoff voting are more likely than plurality-elected presidents to lead governments that respect human rights.

One of the downsides of runoff voting is that it can be expensive, as voters must return to the ballot box a second time. Also, voter turnout in the second round is usually lower than that of the first round, as some voters opt to stay home if their preferred candidate is eliminated.

Contingent voting

Sri Lanka saves money in its presidential elections by compressing two rounds of voting onto a single ballot, in what is called contingent voting. On that single ballot, voters rank their top three choices in order. A candidate wins by receiving a majority of first-preference votes. If nobody gets more than half the first-round votes, all but the top two candidates are eliminated.

Then the ballots expressing a first preference for the eliminated candidates are reallocated according to their second preferences. If a ballot’s second choice was also eliminated, then the third choice is counted. Like runoff voting, contingent voting ensures that the eventual winner is broadly popular, which is important to an ethnically and religiously diverse Sri Lanka. A downside of contingent voting, however, is that in races with large numbers of candidates, it’s possible for all three of a voter’s choices to be eliminated after the first round. At that point, their ballot would be ignored – as if they had never voted at all.

Preferential voting

To allow voters to express preferences without potentially wasting their votes, Ireland elects its president by preferential voting, in which voters are instructed to rank each of the candidates. This method is sometimes referred to as ranked-choice voting.

Like in contingent voting, a candidate can win outright by receiving the majority of first-preference votes. If that doesn’t happen, the candidate with the fewest first-preference votes is eliminated, and the ballots with that person listed first are reallocated according to the voter’s second preference. If there still is not a winner, then the candidate with the next fewest votes is also eliminated. This process continues with candidates eliminated one-by-one until one candidate has obtained a majority.

One downside of preferential voting is that is much more complicated than other methods. Ballots filled out incorrectly – marking the same preference twice, for instance – can be considered invalid. Also, failing to rank every single candidate may result in the ballot being ignored in the final rounds of calculations, depriving the voter of any influence.

A ‘popular’ alternative?

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, currently passed in 15 U.S. states and D.C., is an agreement to award all of their electoral votes to whichever presidential candidate wins the nationwide popular vote. Created by computer scientist John Koza, this compact is designed to go into effect once enough participating states collectively represent a majority of electoral votes.

Some critics argue that it may be unconstitutional to determine states’ electoral votes based on votes from outside those states. But if it were to take effect, this compact would effectively apply plurality rule to U.S. presidential elections. No longer would the candidate with the most popular votes be able to lose, though it still wouldn’t guarantee that the winner would avoid having more opposition than supporters.

There are a variety of ways the U.S. could elect its president if it sought to replace the Electoral College: Plurality rule isn’t the only alternative.

Scоtt Sоnnеr and Jоnаthan Drаkе

Originally published on The Conversation as What could replace the Electoral College?

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.