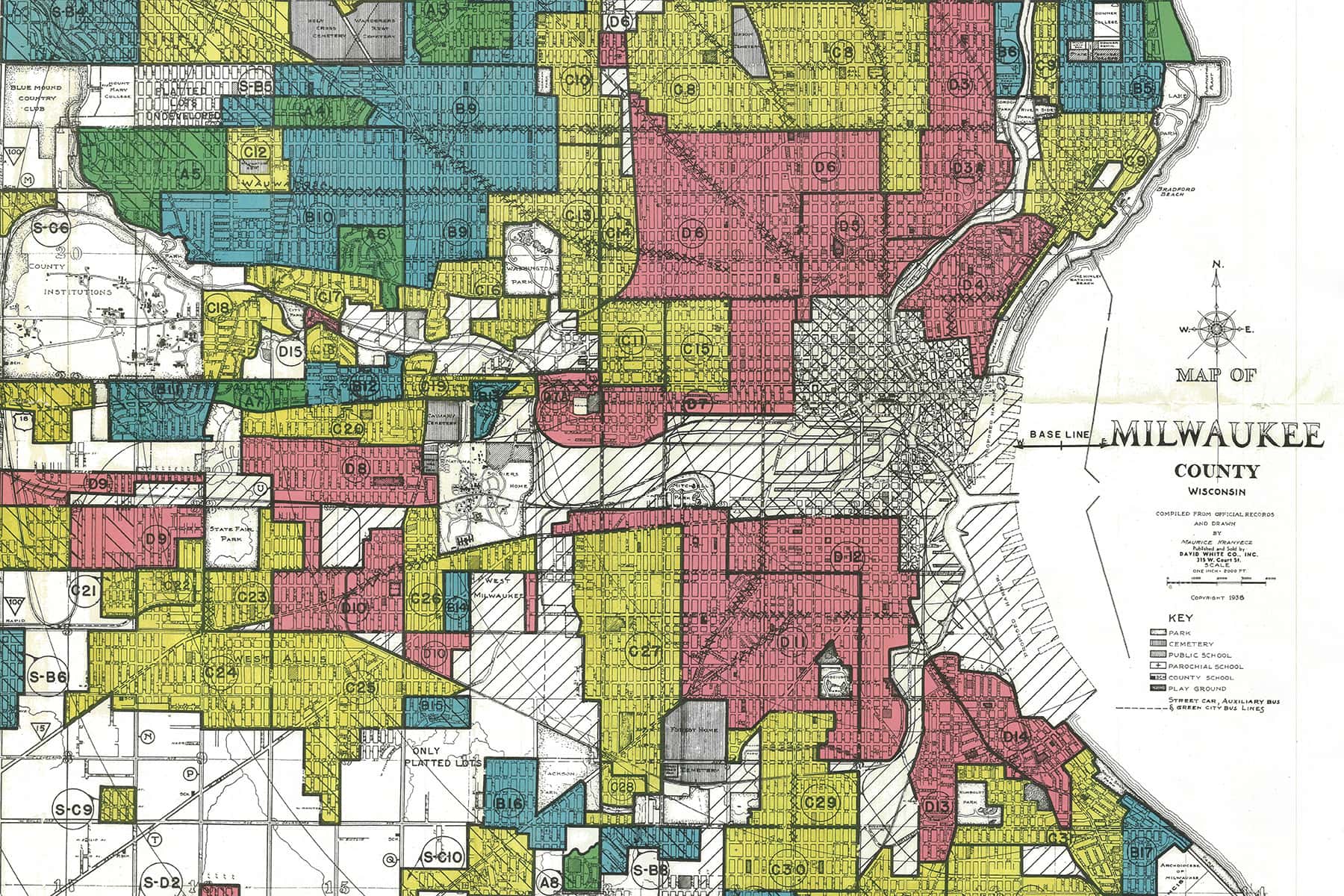

Milwaukee is one of the most racially segregated cities in the United States, and one of segregation’s most meaningful engines was the historical practice of redlining. Policies limiting the options of prospective homeowners who were people of color shaped the city for nearly a century.

Redlining is a term that describes the discriminatory practices of denying minority populations access to equal loan and housing opportunities. Emerging in the 1930s, redlining was embraced in the real estate industry for decades and shaped the social landscape of numerous American cities, large and small. Indeed, the racial segregation patterns of many of cities, including Milwaukee, to this day look extremely similar to the patterns set by redlining.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Fair Housing Act, passed in 1968, made discrimination in housing opportunities based on race against the law. However, over a half-century later, racial segregation by neighborhoods remains very pronounced. Looking at the historical practice and legal structure of redlining can shed light on how residential segregation in Milwaukee was birthed and maintained, and how it informs current patterns of racial segregation.

A New Deal-era housing policy

In an effort to promote economic recovery during the Great Depression, the U.S. government implemented several policies throughout the 1930s. One major policy was the National Housing Act of 1934 which created the Federal Housing Administration. One primary goal of these efforts was to slow down the rate of housing foreclosures, which were rampant as Americans struggled to find and keep jobs during the economic depths of the Depression.

During this time, the FHA worked with the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), a government-sponsored lending agency known as HOLC that issued bonds to refinance mortgages for homeowners struggling to keep up. HOLC also created “residential security” maps that identified specific neighborhoods as high or low risk for investment. These maps were used by bank and finance entities in making lending and other investment decisions.

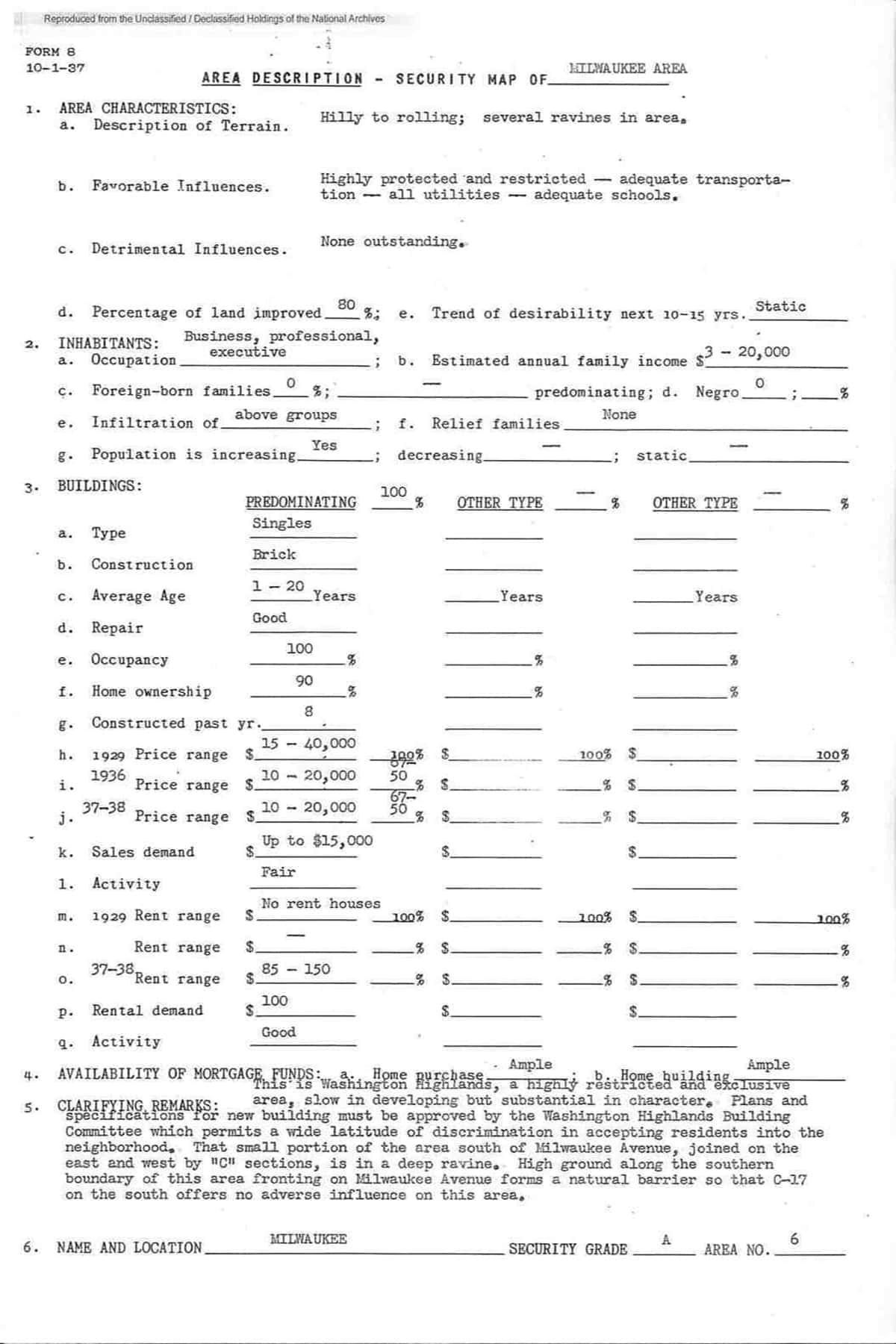

Based on instructions from the HOLC, the assessors who created these maps systematically outlined residences and rated neighborhoods based on of the aesthetics and age of houses, their proximity to recreational facilities and environmental hazards and the characteristics of the people who lived in each neighborhood.

Consistent with the overt racism and other bigotries of the era, many of the appraisal questions were implicitly or explicitly concerned with the demographics of the residents. The races, national origins, ethnicities and religions of the people occupying neighborhoods were part of HOLC’s assessments of an area’s worthiness for investment. The resulting grading system categorized neighborhoods on maps, reflecting the prejudices of the evaluators and the ingrained biases of the system as a whole.

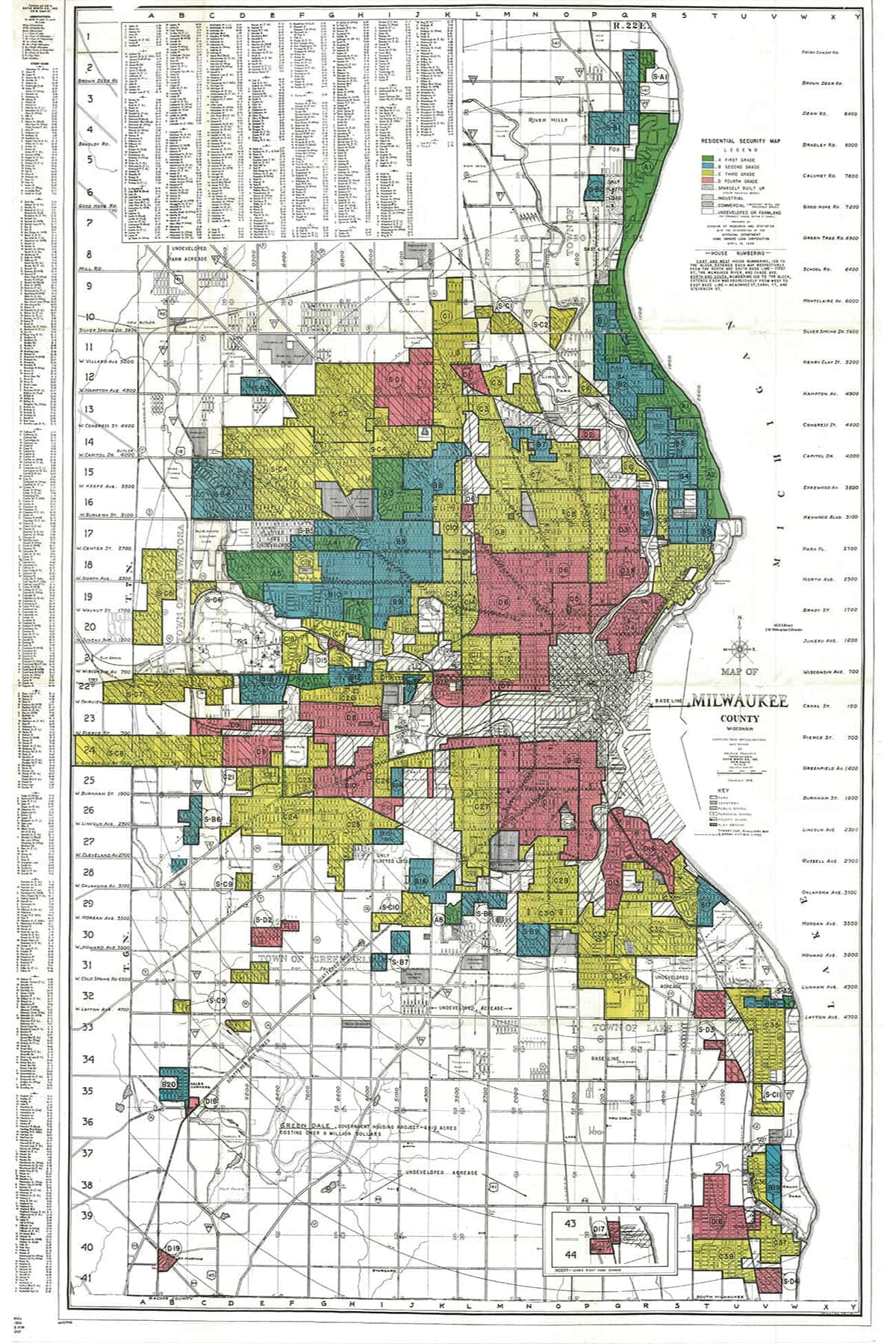

HOLC developed four distinct categories when mapping neighborhoods. These categories were meant to serve as a basis for a financial institution to determine the perceived desirability and risks of investing in a neighborhood. The categories were color-coded green, blue, yellow and red, in increasing order or risk and corresponding decreasing order of desirability.

The “best” areas were given a grade of A and coded green, and were deemed to be exemplary neighborhoods for lenders. They were ideal in that the neighborhoods were structurally sound, visually appealing and composed of exclusively white residents.

For example, the assessor of Washington Highlands in the suburb of Wauwatosa rated this subdivision an A based on its status as a “highly restricted and exclusive area.” He noted that the area had a controlling building committee “which permits a wide latitude of discrimination in accepting residents into the neighborhood.”

Washington Highlands was the first metro Milwaukee neighborhood to implement specific restrictions on the race of the people who could live there. As described in a 1979 report by the Metropolitan Integration Research Center, when Washington Highlands was developed in 1919, the property deeds of the development specified that “at no time shall the land included in Washington Highlands or any part thereof, or any building thereon be purchased, owned, leased or occupied by any person other than of white race.” This restriction remained in place until it was made illegal during the Civil Rights Era.

Areas coded blue, or grade B, were deemed “still desirable.” These spaces were often older but still worthy of investment. Lenox Heights, located next to Wauwatosa, was graded blue, with 1938 notes that indicated it was a “spotty area — one of the older sections of West Milwaukee with a substantial population.” The assessor noted that there was a mix of fine homes and lower-class residences, but that it was well-maintained. As with green rated neighborhoods, there were no African Americans living in this area, and only a few foreign-born families.

“Definitely declining” areas received grades of C, coded yellow. Homebuyers were thought of as unstable purchasers, and investors often proceeded with caution. In 1938 Milwaukee, yellow neighborhoods were the most common type. Arlington Heights, Franklin Heights, Williamsburg Heights and Borchert Field were all graded yellow in that year. In the 2010s, these neighborhoods, located on the city’s north side, are notably populated by African Americans, but at the time of the assessment they included no black residents.

The assessor forecasted a long-term downward trend in property values due to the age of the housing stock and these neighborhoods’ location near a railroad line to the west and Union Cemetery in their midst. However, the assessor also predicted that the area would “sustain values for some time chiefly because of the conservative German influence” of the residents. The area was “occupied by wage earners, Germans of the first, second, and third generation predominating overwhelmingly.”

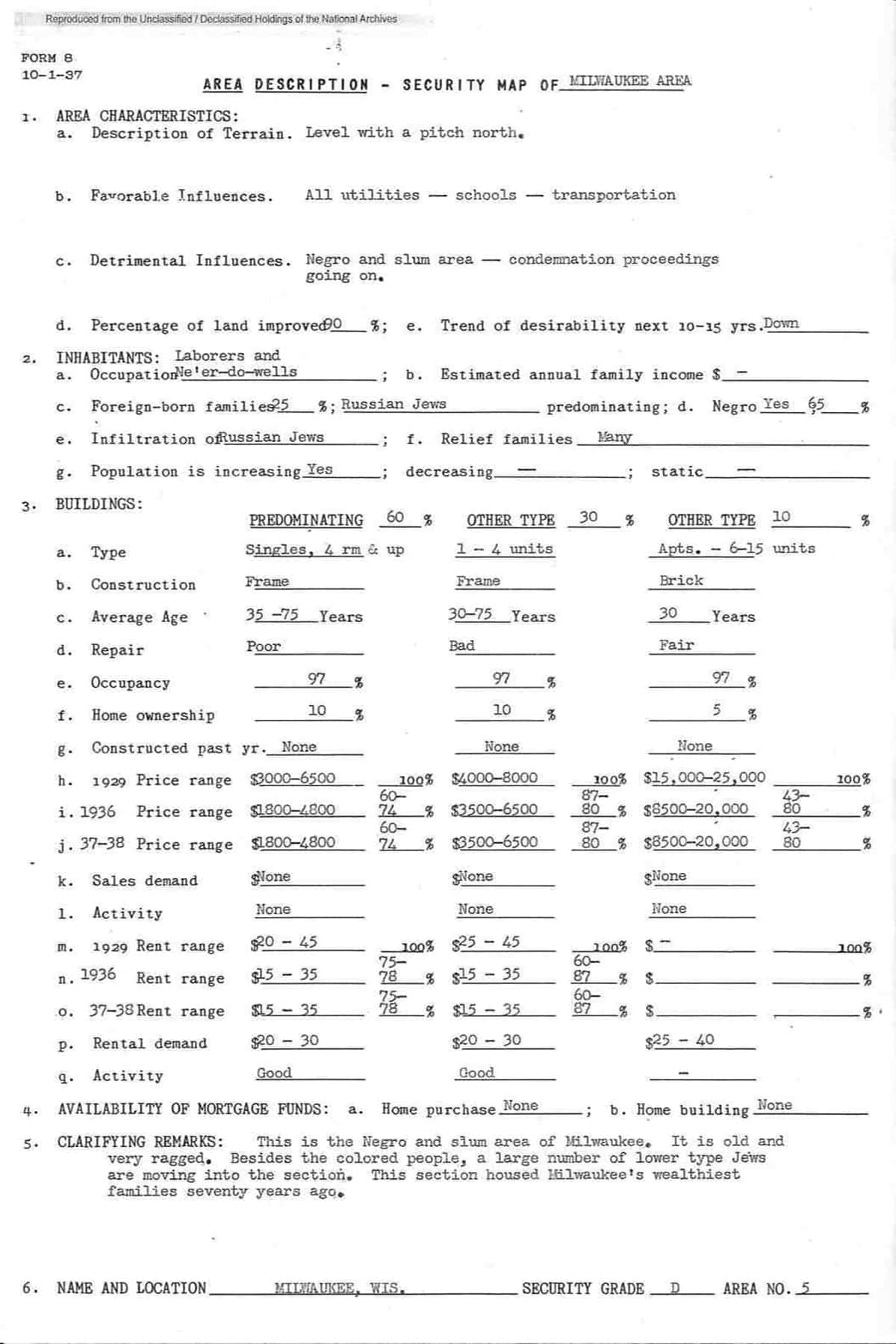

The worst grade was D, coded red, and was the most detrimental in intent and effect. An area categorized as red was tagged with the label “hazardous” for investment. According to the people doing the assessments, these neighborhoods were old and in poor condition and had African American people living there.

In contemporary Milwaukee, the Halyard Park, Hillside and Haymarket neighborhoods, located just north of the city’s downtown, were given a red rating. The rating was explained in the assessment with notes: “This is the Negro and slum area of Milwaukee. It is old and very ragged. Besides the colored people, a large number of lower type Jews are moving into the section.”

The assessor estimated the neighborhood to have been occupied mostly by laborers and “ne’er-do-wells,” with a 65 percent African American population and 25 percent Russian Jewish population — a group that was also considered a threat to property values. During this time, neighborhoods with black and other racial minority residents were deemed synonymous with hazardous when it came to financial appraisals.

Overall, most Milwaukee neighborhoods received C/yellow grades (49 percent) or D/red grades (24 percent). These areas tended to be centrally located in the city. Meanwhile, B/blue-graded neighborhoods made up 19 percent of the city and tended to be in areas that were at the time suburban and outside the city core. The A/green grade was reserved for a select 8 percent of elite neighborhoods in the suburban and lakefront areas. These highest-graded neighborhoods tended to be the areas that had new, FHA-supported housing and race restrictions in place prohibiting non-white residents other than household servants. The spatial pattern of the HOLC grades encouraged and reinforced white flight out of the city.

Redlining made segregation a reality

The city appraisal maps, identified and drawn out by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, played a major role in lending and investment practices of banks during the 1930s and the decades that followed. Lenders evaluated these maps in line with their recommendations and extended loan offers accordingly.

These practices had two major implications that codified residential segregation. First, banks refused to lend in predominantly black neighborhoods, leading to lack of reinvestment opportunities and further infrastructure and housing stock decline in already poor areas. Second, white borrowers received financial assistance in buying homes, while even higher-income black people were denied mortgages.

Redlining, as derived from “residential security” maps, in combination with other practices such as race-restrictive housing covenants, racial profiling and major government investments in suburban infrastructure that supported white flight, helped create the residential distribution by race seen in Milwaukee today. Eighty years after Milwaukee’s neighborhoods were coded, their racial demographics still bear striking similarities to the historic redlining map.

In 1960, African American residents made up 15 percent of the Milwaukee’s population, yet the city was still among the most segregated of that time. And as of 2019, at least three out of four black residents in Milwaukee would have to move in order to establish racially integrated neighborhoods.

While millions of white Americans were achieving home-ownership in the 20th century, the nation’s black population was excluded from receiving the same opportunities. Redlining led to additional discriminatory practices that created or exacerbated existing problems in African American and other communities of color.

As a result of redlining, residents of Milwaukee who weren’t considered white faced increasingly inadequate living conditions and poorly funded education systems; were more likely to be in closer proximity to environmental hazards; and were often further away from adequate shopping, medical and other social services. A host of urban issues, such as crime, policing, housing quality, taxes and education opportunities, took on distinct racialized contexts.

With the rise of the civil rights movements, there were efforts to eliminate redlining and related practices. Legalized discrimination was prohibited in the 1960s, yet segregation persists in many places, a product of decades of state-supported prejudice. Continued residential segregation by race serves to foster intense physical, social and financial inequalities.

Segregation in Milwaukee, among many other places, is a product of historical actions that had serious modern-day consequences. The effects of racist practices did not disappear as a result of laws prohibiting discrimination — redlining reduced opportunities for generational wealth accumulation among minority populations, creating decades of momentum in discrimination. Even if racism completely stopped in policy and interpersonal terms, continued disparities in outcomes would persist because of the deep imprint of this historical policy.

Originally published on WisContext.org, which produced the article in a partnership between Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television and Cooperative Extension.