The Department of Natural Resources has not alerted public water systems to stop flushing before testing, which can understate the level of lead in drinking water.

Nine months after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency warned against flushing water systems before testing for lead, the state Department of Natural Resources has not yet passed that advice on to public water systems in Wisconsin.

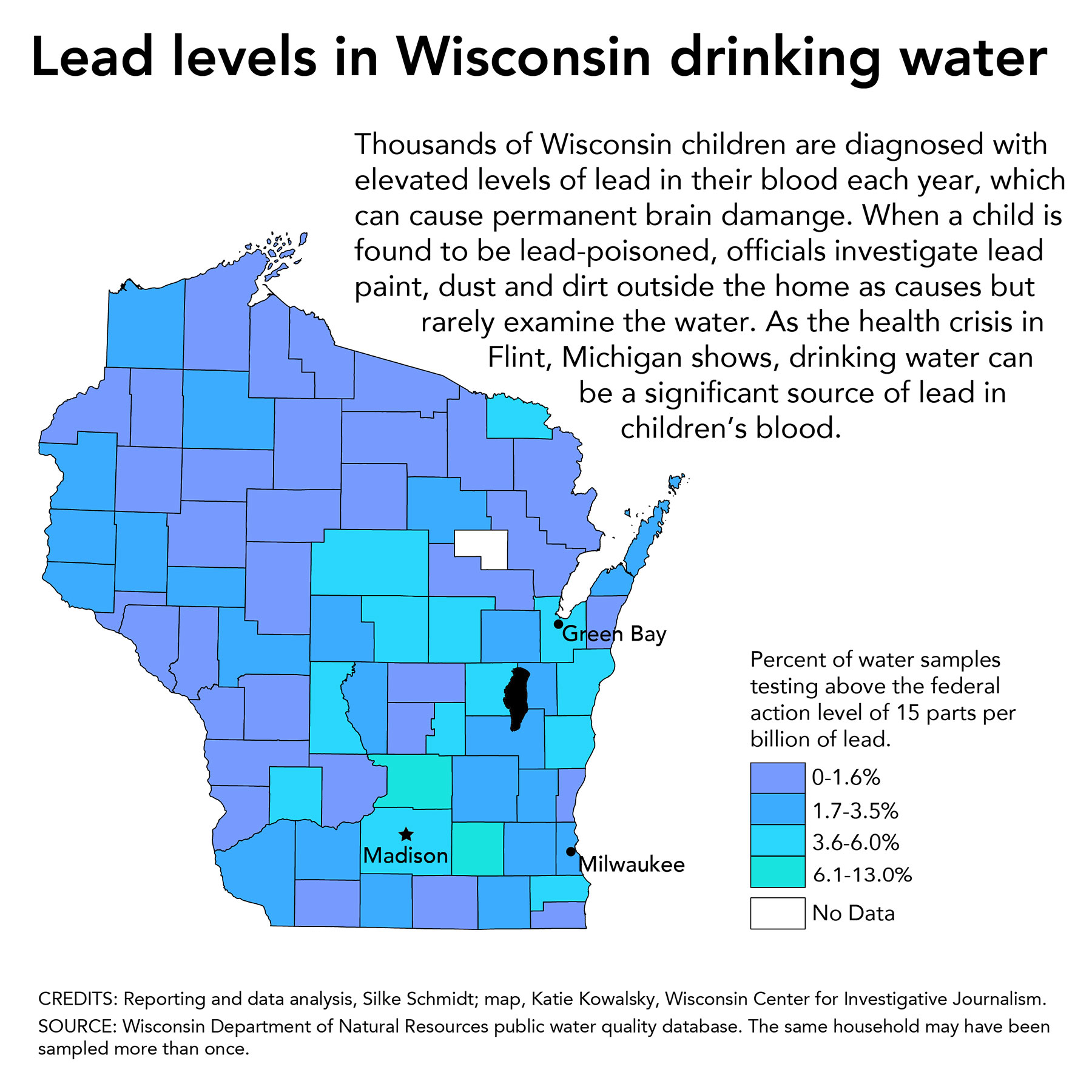

The EPA issued a memo in late February as the lead-in-drinking-water crisis in Flint, Michigan was exploding into public view. The memo, intended to clear up confusion over testing procedures, declared that flushing water systems before sampling must be avoided because it can conceal high levels of lead in drinking water.

Water managers in Shawano and at Riverside Elementary School near Wausau say they were not aware of the change and have continued to use flushing when testing for lead.

Marc Edwards, the Virginia Tech University professor who helped expose the Flint crisis, said that updating the testing procedures is “essential for public health protection.” Any amount of lead can cause permanent damage, including reduced intelligence and behavior problems, according to the EPA. Infants and children are considered the most vulnerable to lead’s negative effects.

“As we saw in Flint, the old protocols effectively ‘hid’ lead in water problems,” Edwards said.

“Given what we now know, data collected using the outdated protocols cannot be trusted.”

The memo also instructed EPA administrators to pass the guidance along to state drinking water program directors. DNR spokeswoman Jennifer Sereno said the agency was notified of the guidance and she confirmed that “pre-stagnation flushing is not an appropriate sampling procedure.”

Sereno insisted the agency had responded appropriately. DNR presented the information at two industry meetings and sent an email to the Wisconsin Rural Water Association in March, she said.

Sereno added that the agency “is in the process of drafting a letter to all community water systems that will make them aware of this and other EPA memos and summarize the content.” The agency, which is responsible for enforcing federal drinking water standards in Wisconsin, expects to send the letters next week, she said.

A search of the DNR drinking water database Friday showed nearly 6,270 lead compliance sample results from 948 water systems have been reported to the agency since Feb. 29, when the EPA guidance was issued.

It was not immediately known how many used the now-discredited procedure of pre-stagnation flushing, in which a water system is flushed for some period of time, water sits unused for six hours, and then samples are collected.

Sampling procedures listed on the DNR’s website indicate the water must be stagnant for six hours but do not address whether or not the tap should be flushed prior to sampling. Sereno said new instructions will be posted online to clarify this.

In July, EPA sent a letter reminding states to post updated protocols to their websites, saying the agency would follow up with each state “to ensure that these protocols and procedures are clearly understood and are being properly implemented to address lead and copper issues at individual drinking water systems.” The EPA did not respond to a question about whether any other states had failed to notify water managers of the updated protocols.

While some municipalities, such as the Green Bay Water Utility and the Milwaukee Water Works, were aware of the EPA memo and updated their testing procedures, others continued using outdated methods that included a flushing step — making it possible dangerous levels of lead could go unnoticed.

Shawano included pre-stagnation flushing in the procedures used for this year’s testing, which was completed over the summer. Patrick Bergner, water manager for the city of nearly 10,000 between Green Bay and Wausau, said although he works closely with a DNR liaison, he was not aware of any EPA guidance against flushing.

“I’d be happy to be informed of any changes in the procedure,” Bergner said. One of Shawano’s 21 compliance samples had a level of lead nearly three times the federal action level, which is 15 parts per billion; several more neared the limit.

DNR public water supply specialist Tony Knipfer acknowledged the need for clarification when flushing is appropriate. It is typically recommended as a way for consumers to reduce exposure to lead in their own homes, for example, but should not be done before testing.

“I think it’s fair to say that there’s been some confusion or conflicting information out on the flushing,” he said. “But from a regulatory aspect and a health and safety aspect, we’re looking for representative samples of what’s likely to be consumed.”

Milwaukee Water Works issued a statement in June saying it immediately adopted the instructions not to pre-flush. Those new instructions will be put to use next year when the utility tests 50 homes and buildings for compliance with EPA regulations.

“Prior to February of 2016, MWW did instruct residents to flush their home plumbing prior to the required six-hour stagnation period, before collecting samples for regulatory compliance purposes,” according to the memo from Milwaukee Water Works Superintendent Carrie Lewis to Mayor Tom Barrett.

“The last testing cycle (for Milwaukee) was the summer of 2014. That cycle did include the pre-stagnation flushing instruction,” Lewis wrote. “The next cycle in the summer of 2017 will not.”

Other procedures that can mask the true level of lead in drinking water include removing or cleaning faucet filters called aerators that can collect lead particles; using narrow-necked bottles that result in a slower flow of water; and sampling in cooler months when lead concentrations are lower. The EPA also urged that those procedures should end.

“While we cannot undo the past harm done from failing to detect water lead risks,” Edwards said, “there should be zero tolerance for future needless harm that arises from a false sense of security created by bad data.”

Cara Lombardo and Dee J. Hall

Courtesy of Milwaukee Water Works

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.