In Wisconsin, much of the discussions around water quality have been focused on contaminants including lead and PFAS.

But George Kraft, UW-Stevens Point emeritus professor and emeritus director of the Center for Watershed Science and Education, says his biggest concerns looking to the future are nitrates and pesticides from agricultural runoff.

“Instead of something that we see going away, it’s going the other direction,” Kraft said during an online panel discussion of water quality’s impacts on public health.

Thursday’s panel discussion was a collaboration between the National Institutes of Health All of Us Research Program, the Marshfield Clinic Health System and American Public Health Association. It focused on how environmental conditions affect health outcomes. Kate Robb, deputy director of the Center for Public Health Policy at the American Public Health Association, said social determinants, the “conditions in the environment where people are born, live, learn, work, play and pray… affect a wide range of health functioning, quality of life outcomes and risks.”

“It’s really important to acknowledge social determinants can be more important in influencing your health than health care and lifestyle choices,” said Robb.

Kraft pointed out that “we’ve done a good job over the past decades, cleaning up things like landfills, hazardous waste sites, leaky underground storage tanks, that sort of thing.” With PFAS (Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), Kraft said the growing number of contamination sites is “concerning and we need to take care of it, but I think we’re gonna find that that is going to be geographically limited in scope.”

“There’s a lot of the hot places we see now — Wausau, Eau Claire, Marinette,” Kraft said. “We’re going to be finding more of those, but I think that’s something we’re gonna be getting a grip on. I hate to make a prediction, but maybe 10 years from now we’ll be in the rear-view mirror on this.”

Meanwhile the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, citing Kraft’s research, has found that despite widespread knowledge of the risk of nitrates to humans, contamination has gotten worse over time. In fact, nitrates are the most widespread groundwater contaminant in Wisconsin. Statewide, about 10% of private wells sampled exceed the maximum contaminant level; in some areas of the state that rate can be as high as 20-30%.

Initially the groundwater standards for nitrates were set to protect infants from methemoglobinemia, or “blue baby syndrome.” According to the Wisconsin Department of Health, nitrate can affect how oxygen is carried in the blood, causing babies to turn bluish or gray, and can cause “weakness, excess heart rate, fatigue, and dizziness.”

Further research has found it also increases the risk of birth defects, thyroid cancer, and colon cancer, though Mark Borchardt, a microbiologist at the USDA-Agricultural Research Service, said it’s been difficult for epidemiologists to “tease apart” the impacts of exposure through drinking water versus food.

Another challenge in dealing with the issues is that the financial toll is spread out among small rural communities. Kraft said the health care cost of nitrate contamination could range from $23 to $80 million in Wisconsin. And the cost to replace contaminated wells across the state could be as high as $400 million.

“And we have these small communities, 1,000, 5,000, 10,000 people; They’re having to put up a million bucks to get their community assistance,” Kraft said. “It’s a large, widespread and uncontrolled problem that we have.”

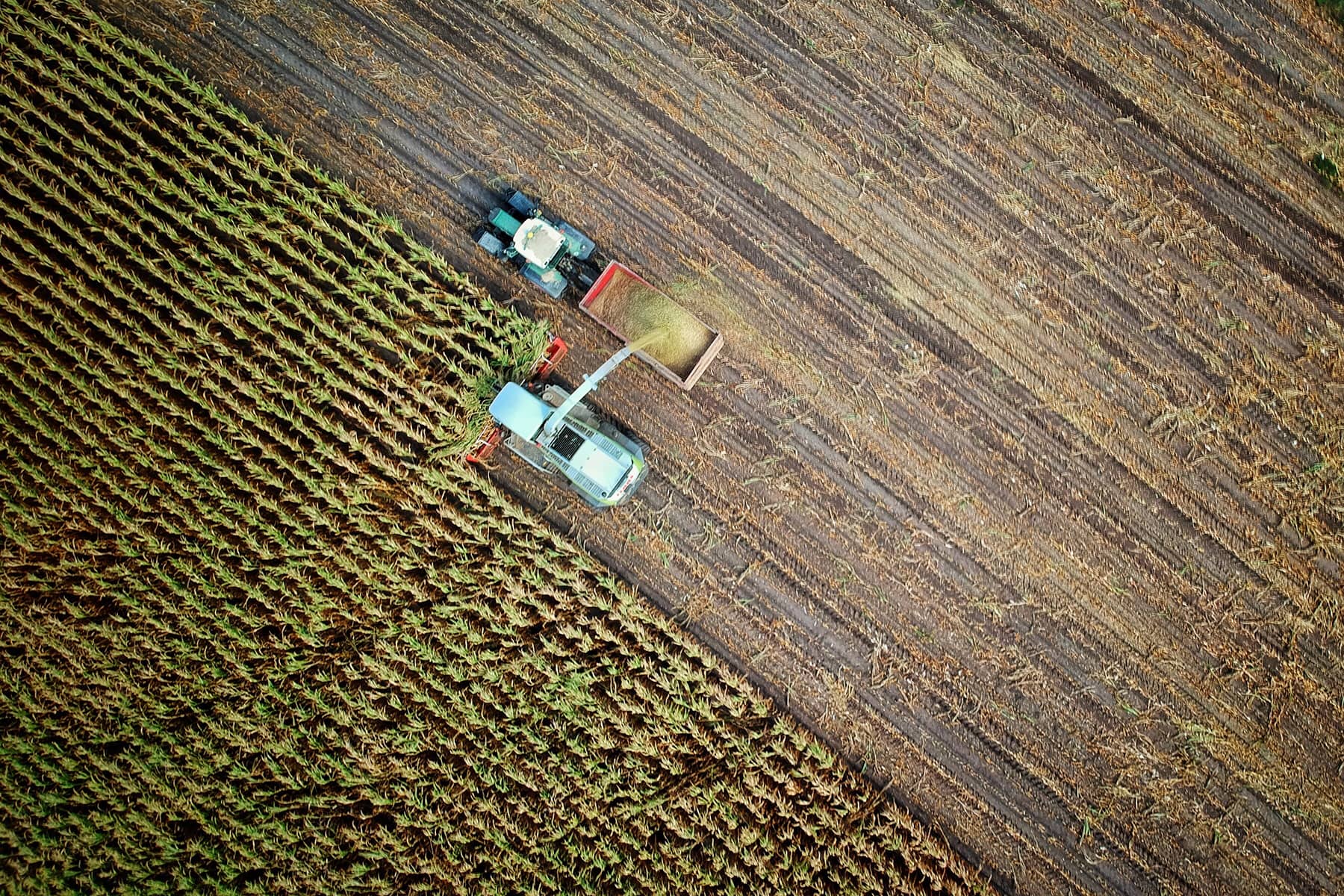

Also, the source of the contamination — agriculture — is the lifeblood of rural communities, which has made reducing the contamination at its source challenging.

“We’ve been involved in trying to ignore this issue for decades,” Kraft said. “It’s tied up into the issue that recommendations for farmers are to put nitrogen fertilizer on to maximize profitability… We have a goal: we wanna keep family farms on the land. We have policies that encourage more production, even when we don’t need it.”

“In the big picture, we need to think about what the agricultural future looks like for our drinking water, ground water, surface water,” Kraft said.

The UW-Stevens Point Center for Watershed Science and Education website has information on groundwater contamination and private well testing.

Christina Lieffring

Originally published on the Wisconsin Examiner as Agricultural runoff an overlooked threat to public health

Donate: Wisconsin Examiner

Help spread Wisconsin news, relentless reporting, unheard voices, and untold stories. Make a difference with a tax-deductible contribution to the Wisconsin Examiner