The City of Milwaukee has one documented case of a lynching, involving George Marshall Clark in 1861. For the following 14 years until 1875, eight lynchings took place in Wisconsin.

Historians have devoted in-depth analysis to the lynchings that took place in the Southern United States, and some that occurred in Western states and territories. But the mob violence directed at people of color that occurred in the Midwest has gone relatively unexamined.

What were lynchings?

Historians broadly agree that lynchings were a method of social and racial control meant to terrorize Black Americans into submission, and into an inferior racial caste position. They became widely practiced in the US south from roughly 1877, the end of post-civil war reconstruction, through 1950.

A typical lynching would involve criminal accusations, often dubious, against a Black American, an arrest, and the assembly of a “lynch mob” intent on subverting the normal constitutional judicial process. Victims would be seized and subjected to every imaginable manner of physical torment, with the torture usually ending with being hung from a tree and set on fire. More often than not, victims would be dismembered and mob members would take pieces of their flesh and bone as souvenirs.

In a great many cases, the mobs were aided and abetted by law enforcement (indeed, they often were the same people). Officers would routinely leave a Black inmate’s jail cell unguarded after rumors of a lynching began to circulate to allow for a mob to kill them before any trial or legal defense could take place.

What would trigger a lynching?

Chief among the trespasses – occasionally real, but usually imagined – was any claim of sexual contact between Black men and White Women. The trope of the hypersexual and lascivious Black male, especially vis-a-vis the inviolable chastity of White women, was and remains one of the most durable tropes of White Supremacy. According to the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), nearly 25% of lynching victims were accused of sexual assault. Nearly 30% were accused of murder.

“The mob wanted the lynching to carry a significance that transcended the specific act of punishment,” wrote the historian Howard Smead in Blood Justice: The Lynching of Mack Charles Parker. The mob “turned the act into a symbolic rite in which the Black victim became the representative of his race and, as such, was being disciplined for more than a single crime … The deadly act was [a] warning [to] the Black population not to challenge the supremacy of the White race.”

How many took place in America?

Because of the nature of lynchings – summary executions that occurred outside the constraints of court documentation – there was no formal, centralized tracking of the phenomenon. Most historians believe this has left the true number of lynchings dramatically underreported.

For decades, the most comprehensive total belonged to the archives at the Tuskegee Institute, which tabulated 4,743 people who died at the hands of US lynch mobs between 1881 and 1968. According to the Tuskegee numbers, 3,446 (nearly three-quarters) of those lynched were Black Americans.

The EJI, which relied on the Tuskegee numbers in building its own count, integrated other sources, such as newspaper archives and other historical records, to arrive at a total of 4,084 racial terror lynchings in 12 southern states between the end of Reconstruction in 1877 and 1950, and another 300 in other states. Unlike the Tuskegee data, EJI’s numbers attempt to exclude incidents it considered acts of “mob violence” that followed a legitimate criminal trial process or that “were committed against non-minorities without the threat of terror.”

Where did most lynchings take place?

Unsurprisingly, lynching was most concentrated in the former Confederate states, and especially in those with large Black populations. According to EJI’s data, Mississippi, Florida, Arkаnsаs and Louisiana had the highest statewide rates of lynching in the United States. Mississippi, Georgia, and Louisiana had the highest number of lynchings.

Who attended lynchings?

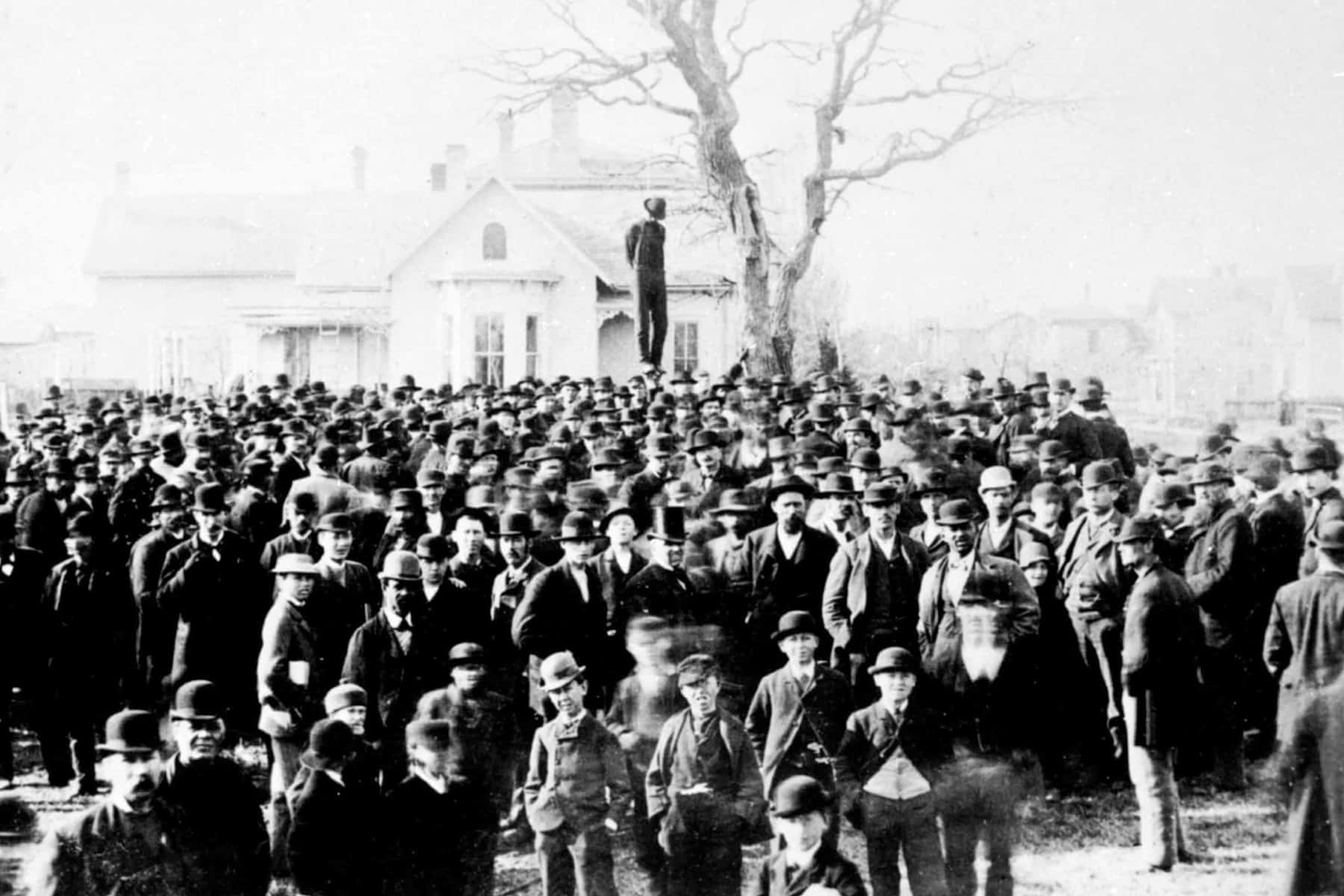

Among the most unsettling realities of lynching is the degree to which White Americans embraced it, not as an uncomfortable necessity or a way of maintaining order, but as a joyous moment of wholesome celebration.

“Whole families came together, mothers and fathers, bringing even their youngest children. It was the show of the countryside – a very popular show,” read a 1930 editorial in the Raleigh News and Observer. “Men joked loudly at the sight of the bleeding body … girls giggled as the flies fed on the blood that dripped from the Negro’s nose.”

Adding to the macabre nature of the scene, lynching victims were typically dismembered into pieces of human trophy for mob members. In his autobiography, W.E.B. Du Bois wrote of the 1899 lynching of Sam Hose in Georgia. He reported that the knuckles of the victim were on display at a local store on Mitchell Street in Atlanta, and that a piece of the man’s heart and liver was presented to the state’s governor.

In the 1931 Maryville, Missouri, lynching of Raymond Gunn, the crowd estimated at 2,000 to 4,000 was at least a quarter women, and included hundreds of children. One woman “held her little girl up so she could get a better view of the naked Negro blazing on the roof,” wrote Arthur Raper in The Tragedy of Lynching.

After the fire was out, hundreds poked about in his ashes for souvenirs. “The charred remains of the victim were divided piece by piece,” wrote Raper.

What was the political context at the time?

Lynchings were only the latest fashion in racial terrorism against Black Americans when they came to the fore in the late 19th century. White planters had long used malevolent and highly visible violence against the enslaved to try to suppress even the vaguest rumors of insurrection. In 1811, after a failed insurrection outside New Orleans, for example, Whites decorated the road to the plantation where the plot failed with the decapitated heads of Blacks, many of whom planters later admitted had nothing to do with the revolt.

It was not a southern-specific phenomenon, either. In 1712, colonial authorities in New York City manacled, burned and broke on the wheel 18 enslaved Blacks accused of plotting for their freedom. Communities of free Blacks also faced the constant threat of race riots and pogroms at the hands of White mobs throughout the 19th century and continuing into the lynching era.

Among the best known of these was the decimation of the Tulsa, Oklahoma, neighborhood of Greenwood in 1921, after a Black man was falsely charged with raping a White woman in an elevator. The Greenwood neighborhood was sometimes referred to as “Black Wall Street” for its economic vitality before the massacre. According to the Tulsa Historical Society, it is believed 100 to 300 Blacks were killed by White mobs in a matter of a few hours.

Similar events, from the New York draft riots during the civil war to others in New Orleans, Knoxville, Charleston, Chicago, and St. Louis, saw hundreds of Blacks killed.

The start of the lynching era is commonly pegged to 1877, the year of the Tilden-Hayes compromise, which is viewed by most historians as the official end of Reconstruction in the US south. In order to settle a razor-thin and contested presidential election between the Republican Rutherford B Hayes and the Democrat Samuel Tilden, northern Republicans agreed to withdraw federal troops from the last of the formerly renegade states.

The move technically only affected South Carolina and Louisiana, but symbolically gestured to the South that the north would no longer hold the former Confederacy to the promise of full citizenship for freed Blacks, and the south jumped at the chance to renege on the pledge. The end of Reconstruction ushered in a widespread campaign of racial terror and oppression against newly freed Black Americans, of which lynching was a cornerstone.

Were people ever punished for carrying out lynchings?

The vast majority of lynching participants were never punished, both because of the tacit approval of law enforcement, and because dozens if not hundreds often had a hand in the killing. Still, punishment was not unheard of – though most of the time, if White lynchers were tried or convicted, it was for arson, rioting or some other much more minor offense. According to EJI, of all lynchings committed after 1900, only 1% resulted in a lyncher being convicted of a criminal offense of any kind.

When and how did lynchings end?

Lynchings slowed in the middle of the 20th century with the coming of the civil rights movement. Anti-lynching efforts predominantly led by women’s organizations had a measurable effect, helping to generate overwhelming White support for an anti-lynching bill by 1937 (though such legislation never made it past the filibusters of southern Dixiecrats in the Senate).

Also playing a major role was the great migration of Black people out of the south into urban areas north and west. The exodus of some 6 million Black Americans between 1910 and 1970 was pushed by racial terror and a waning agricultural economy and pulled by a surfeit of industrial job opportunities.

The year 1952 was the first since people began keeping track that there were no recorded lynchings. When it happened again in 1953, Tuskegee suspended its data collection, suggesting that as traditionally defined, lynching had ceased to be a useful “barometer for measuring the status of race relations in the United States”.

But foregrounding the intense new waves of brutality that would greet the nascent civil rights movement, Tuskegee continued in its final lynching report that the terror was switching modes by “the development of other extra-legal means of control, such as bombings, incendiarism, threats and intimidation”.

In The End of American Lynching, Ashraf HA Rushdy argued: “The violence meant to act as a form of social control and terrorism had become less ritualistic and less collective. Individuals and small groups could throw bombs, perform drive-by shootings and torch a house,” as the resurgence of the KKK and similar violent White hate groups proved.

The end of lynching cannot be said to be purely academic, though. While targeted violence against Black people did not end with the lynching era, the element of public spectacle and open, even celebratory participation was a unique social phenomenon that would not be reborn in the same way as racial violence evolved. Despite the shift, the specter of ritual Black death as a public affair – one that people could confidently participate in without anonymity and that could be seen as entertainment – did not end with the lynching era.

Who took a stand against them at the time?

Generally speaking and especially early on, the White press wrote sympathetically about lynchings and their necessity to preserve order in the south. The Memphis Evening Scimitar published in 1892:

Aside from the violation of White women by Negroes, which is the outcropping of a bestial perversion of instinct, the chief cause of trouble between the races in the South is the Negro’s lack of manners. In the state of slavery he learned politeness from association with White people who took pains to teach him. Since the emancipation came and the tie of mutual interest and regard between master and servant was broken, the Negro has drifted away into a state which is neither freedom nor bondage … In consequence there are many negroes who use every opportunity to make themselves offensive, particularly when they think it can be done with impunity … We have had too many instances right here in Memphis to doubt this, and our experience is not exceptional. The White people won’t stand this sort of thing, and … the response will be prompt and effectual.

The Black press, on the other hand, was arguably the primary force in fighting against the phenomenon. The Memphis journalist Ida B. Wells was the most strident and devoted anti-lynching advocate in US history, and spent a 40-year-career writing, researching and speaking on the horrors of the practice. As a young woman she travelled the south for months, chronicling lynchings and gathering empirical data.

Wells eventually became an owner of the Memphis Free Speech and Headlight before being chased out of town by White mobs and relocating to New York and then Chicago. Eventually many White publications began to turn with overall White attitudes about lynching. “Missouri in Shame” was the headline of the first editorial in the Kаnsаs City Star on the 1931 Maryville Lynching of Raymond Gunn. It read, in part:

The lynching at Maryville was about as horrible as such a thing can be. Lynching in itself is a fearful reproach to American civilization. Lynching by fire is the vengeance of a savage past … The sickening outrage is the more deplorable because it easily could have been prevented.

Jаmіlеs Lаrtеy and Sаm Mоrrіs

Library of Congress

Portions originally published on The Guardian as How white Americans used lynchings to terrorize and control black people

Help deliver the independent journalism that the world needs, make a contribution of support to The Guardian.