By Thomas Alan Schwartz, Professor of History, Vanderbilt University; and Catesby Holmes, The Conversation US

“While they are very different, many are looking at the 1975 fall of Saigon to try to understand what is happening in Afghanistan. Walter Cronkite perhaps said it best, ‘We’ve reached the end of a tunnel and there is no light.’” – Ken Burns

As headlines proclaim the “end” of “America’s longest war,” President Joe Biden’s withdrawal of the remaining U.S. military personnel from Afghanistan is being covered by some in the news media as though it means the end of the conflict, or even means peace, in Afghanistan. It most certainly does not.

For one thing, the war is not actually ending, even if the U.S. participation has. Disengagement from an armed conflict is common U.S. practice in recent decades – since the 1970s, the country’s military has simply left Vietnam, Iraq and now Afghanistan. But for much of the country’s history, Americans won their wars decisively, with the complete surrender of enemy forces and the home front’s perception of total victory.

A history of triumph

The American Revolution, of course, was the country’s first successful war, creating the nation. The War of 1812, sometimes called the Second War of Independence, failed in both its goals, of ending the British practice of forcing American mariners into the Royal Navy and conquering Canada. But then-Major General Andrew Jackson’s overwhelming triumph at the Battle of New Orleans allowed Americans to think they had won that war.

In the 1840s, the U.S. defeated Mexico and seized half its territory. In the 1860s, the United States defeated and occupied the secessionist Confederate States of America. In 1898 the Americans drove the Spanish out of Cuba and the Philippines.

America’s late entry into World War I tipped the balance in favor of Allied victory, but the postwar acrimony over America’s refusal to enter the League of Nations, followed by the Great Depression and the rise of fascism, eventually soured Americans on the war’s outcome as well as any involvement in Europe’s problems.

That disillusionment led to the strident campaigns to prevent the U.S. from intervening in World War II, with the slogan “America First.” When the U.S. did enter the war after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt demanded the “unconditional surrender” of both Germany and Japan.

The discovery of the Nazi death camps gave the war its profound justification, while the Japanese surrender on the battleship Missouri in 1945 became a symbol of unparalleled American power and victory. It was perhaps captured best by the words of the American general who accepted that surrender, Douglas MacArthur: “In war there is no substitute for victory.”

Lasting connections

After World War II, the United States kept substantial military presences in both Germany and Japan, and encouraged the creation of democratic governments and the development of what ultimately became economic powerhouses.

The U.S. stayed in those defeated nations not with the express purpose of rebuilding them, but rather as part of the post-war effort to contain the expanding influence of its former ally, the Soviet Union.

Nuclear weapons on both sides made all-out war between the superpowers unthinkable, but more limited conflicts were possible. Over the five decades of the Cold War, the U.S. fought at arm’s length against the Soviets in Korea and Vietnam, with outcomes shaped as much by domestic political pressures as by foreign policy concerns.

In Korea, the war between the communist-backed North and the U.S.- and U.N.-backed South ended with a 1953 armistice that ended major combat, but was not a victory for either side. U.S. troops remain in Korea to this day, providing security against a possible North Korean attack, which has helped allow the South Koreans to develop a prosperous democratic country.

A humbling loss

In Vietnam, by contrast, the U.S. ended its involvement with a treaty, the Paris Peace Accords of 1973, and pulled out all U.S. troops. Richard Nixon had vowed early in his presidency that he would not be “the first American president to lose a war,” and used the treaty to proclaim that he had achieved “peace with honor.”

But all the peace agreement had really done was create what historians have called a “decent interval,” a two-year period in which South Vietnam could continue to exist as an independent country before North Vietnam rearmed and invaded. Nixon and his chief foreign policy adviser, Henry Kissinger, were focused on the enormous domestic pressure to end the war and get American prisoners of war released. They hoped South Vietnam’s inevitable collapse two years later would be blamed on the Vietnamese themselves.

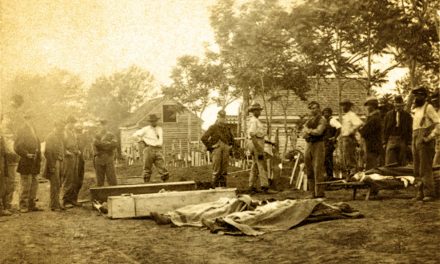

But the speed of the North Vietnamese victory in 1975, symbolized by masses seeking helicopter evacuations from the roof of the U.S. Embassy in Saigon, revealed the embarrassment of American defeat. The postwar flight of millions of Vietnamese made “peace with honor” an empty slogan, hollowed further by the millions murdered in Cambodia by the Khmer Rouge, who overthrew the U.S.-supported government as troops withdrew from Southeast Asia.

The choice to withdraw

President George H.W. Bush thought the decisive American victory in the Persian Gulf War in February 1991 “kicked the Vietnam syndrome,” meaning that Americans were overcoming their reluctance to use military force in defense of their interests.

However, Bush’s 90% popularity at the end of that war faded quickly, as Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein remained in power and the U.S. economic recession took the spotlight. One bumper sticker in the 1992 presidential campaign said, “Saddam Hussein has a job. Do you?”

In 2003 President George W. Bush sought to avoid his father’s mistake. He sent troops all the way to Baghdad and ousted Saddam, but this decision embroiled the United States in a frustrating counterinsurgency war whose popularity rapidly declined.

Barack Obama campaigned in 2008 in part on contrasting the bad “war of choice” in Iraq with the good “war of necessity” in Afghanistan, and then withdrew from Iraq in 2011 while boosting American forces in Afghanistan. However, the rise of the Islamic State group in Iraq required Obama to send American forces back into that country, and the Afghanistan surge did not yield anything approaching a decisive result.

Now, Biden has decided to end America’s war in Afghanistan. Public opinion polls indicate widespread support for this, and Biden seems determined, despite the advice of the military and predictions of civil war. The fact that President Donald Trump also wanted to pull out of Afghanistan would seem to indicate there is little domestic political risk.

EDITOR’S NOTE: An update on the speed of Afghanistan’s collapse

On August 15, the president of Afghanistan fled and the government apparently had fallen, after Taliban insurgents captured the capital city of Kabul. The Taliban also seized the presidential palace. There would be “no transitional government in Afghanistan,” Taliban officials said. The insurgent group “expects a complete handover of power.”

Panicked citizens aiming to escape the rule of radical Islamic fighters were “lining up at cash machines to withdraw their life savings.” The apparent fall of Afghanistan came just three months after the U.S. began to withdraw its troops from the country following a 20-year war that killed 2,448 U.S. service members, 3,846 U.S. military contractors and 66,000 Afghan national military and police.

For Afghans and international observers of a certain age, it looks like history is repeating itself. The Taliban – which means “the students” in Pashto – seized control of Afghanistan in 1996 after capturing Kabul from various rival groups in the Afghan civil war. They established a government based on their extreme interpretation of Islamic Sharia law and ruled for five years. The Taliban regime was then toppled in 2001 by the American-led invasion of Afghanistan.

Аfghаn Mіnіstry of Dеfеnsе Prеss Оffice

Originally published on The Conversation as In Afghanistan, the US again gets to choose how it stops fighting

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.