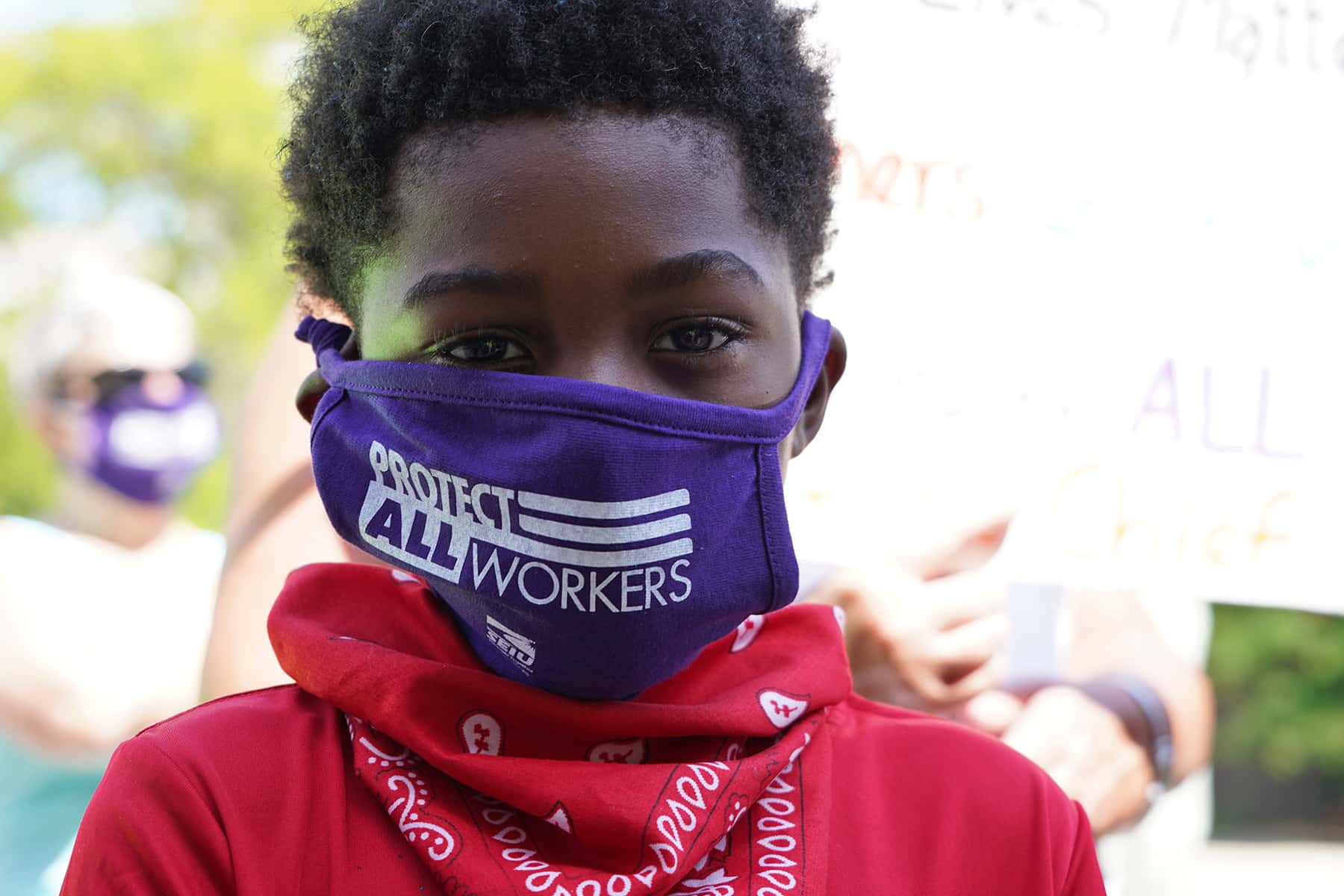

Racism and health care inequities were already making families and children sick. The coronavirus pandemic is making a dire situation worse.

The COVID-19 pandemic is killing Black Americans at a much higher rate than white Americans. And, although most children develop a mild case of the infection, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has now warned that Black and Hispanic children are especially vulnerable to a severe form of the virus. Sadly, research scientists would tell you this is no surprise. The CDC study is just one of several published over the past few decades to show that people of color are more vulnerable to a range of health threats than their white counterparts are.

Studies have shown that racism makes people more vulnerable to common colds, obesity and higher rates of cancer. Black women are up to four times more likely to die of pregnancy-related complications than white women. According to most recent CDC data, for every 1,000 live births, 4.8 white infants die before their first birthday. But for Black babies, that number is 11.7. The average life expectancy of Blacks is four years lower than the rest of the U.S. population.

The cause cited by many is racial inequities in health care. The American Medical Association, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the American College of Emergency Physicians have all declared institutional racism an urgent public health issue. Dr. Igda Martinez, clinical psychologist and director of behavioral health at The Floating Hospital in New York City, welcomes the declarations but warns that fixing the problems will take time.

“This is so multi-layered and complex. We are seeing an uptick in the urgency of demands for social justice — in health, education and politics,” says Martinez. “But, unfortunately, the responsibility continues to fall on the people who are suffering.”

For the past 150 years, The Floating Hospital (TFH) has been working to shift that burden by providing health care to New York families and children regardless of their insurance status, immigration status or ability to pay. Here, Martinez draws from her 12 years of experience as a clinical psychologist to talk about why racism makes people sick and how her clients — many of them from families living in temporary housing and domestic safe houses — are coping with the twin pandemics of COVID-19 and racism.

Underlying conditions such as heart disease, diabetes and asthma make people more vulnerable to the virus, and Black Americans are more likely to have those diseases than white Americans. Why is that?

DR. IGDA MARTINEZ: A multitude of factors contribute to these conditions. Researchers have found that chronic exposure to discrimination sets off a chain reaction of physiological changes. The most studied long-term effects of racism are around the impact of sustained arousal, hypervigilance and chronic stress, which elevate your body’s levels of cortisol, the stress hormone that prepares you to fight or take flight. Elevated cortisol impacts your body at a cellular level and can trigger spikes in blood sugar, rapid breathing, sharpened senses and increased heart rate. Studies have also shown that people of color maintain elevated blood pressure when they sleep. Sleep is supposed to be restorative, a time when the body gets to cool down, regenerate and reset. But chronic racism means that sleep can’t even offer relief.

Can you talk about the societal factors that contribute to the constant stress your clients face?

DR. IGDA MARTINEZ: Many things keep cortisol levels dangerously high. Unfair mortgage lending practices, for example, make it very difficult for our clients to buy a house. If you can’t afford to live in a neighborhood with good public schools, your children won’t get the same chances that children who have access to enriching public education will. Many of our clients live in shelters located in food deserts, where fast food is the only option, and they can only afford things on the dollar menu because produce is too expensive. Then there are inequities on the job, microaggressions and inaccessible promotion tracks. One thing leads to another. All of these experiences of systemic racism, which are compounded by the institutional racism within the health care system, can make it extremely difficult for people of color to get appropriate, timely and culturally sensitive treatment.

Why do people of color find the U.S. health care system so difficult to navigate?

DR. IGDA MARTINEZ: For starters, just accessing care is difficult. If you don’t have health insurance, you can’t afford to take care of yourself or your children. Then, can you even get to a provider, and if you do, will the provider understand who you are and where you are coming from? Unfortunately, a disproportionate number of providers don’t represent the patients they serve, which means that often providers come from socioeconomic, racial and other demographic groups that differ from the patients under their care. That’s especially a problem because if providers don’t understand what it’s like for the global majority to experience the day-to-day stress of systemic racism, then people start to distrust the system.

How do all these factors impact children’s health?

DR. IGDA MARTINEZ: When pregnant women experience this kind of stress, the baby is affected, and the changes begin in utero. Studies consistently show children born to Black women are often born prematurely and at lower birth weights. These babies also come into the world with measurably increased stress levels and a heightened startle response. So, the stress of racism has already affected their neural networks. That’s just the physiological piece. Racism’s psychological impacts also affect the kind of care a parent can provide and what they teach their children.

How hard must Black and Brown parents struggle to get their children the care they need?

DR. IGDA MARTINEZ: Since 1999, studies have shown that implicit biases affect the medical care Black people receive. Even when controlling for years of experience in the medical field, these studies still found an alarming number of providers with implicit biases against people of color. Those biases affect the recommendations they make. It’s a rare doctor who isn’t under a lot of pressure to make many quick medical decisions during the few minutes he or she spends with every patient. But multiple studies have shown that Black and white patients won’t get the same recommendations or standard of care — from dialysis to treatment for diabetes to referrals to specialists. These omissions will affect longevity but also the care Black parents seek out for their children. When everything is a struggle — even something that should be simple, like getting their children routine immunizations — Black parents may feel they have no voice in health care, that their concerns are disregarded or that they can’t trust the health care system to provide the best care for their needs.

What kind of message does this send to children about the importance of their health and well-being?

DR. IGDA MARTINEZ: We know that racism has a complex interactive effect on children. Their first five years are incredibly important for development overall. They need good nutrition, the right kind of stimulation and regular well-visits so they receive all the routine immunizations that are the foundation for future good health and well-being. The many hurdles families of color face can get in the way of children receiving these essentials. Between the ages of 7 and 10, children establish racial permanency. That’s when they understand differences and racial categories and the value that society places on their cultural group. In elementary school, children are already getting messages explicitly and implicitly about who they are and what that means in the world. As they get older, children who don’t get adequate treatment to process these experiences can start to make misattributions in social contexts that can lead to a bunch of other negative social impacts.

How does chronic racism affect the way kids see the world?

DR. IGDA MARTINEZ: As children get older the cumulative effect of racism causes hypervigilance. It’s like they’re constantly looking over their shoulder for a potential threat. This can cause children to make misattributions. So let’s say I’m a kid walking into the cafeteria during lunch period and I hear kids laughing as I walk by. I might misattribute that laughter and think they are laughing at me or think badly of me. That can trigger anger or maybe embarrassment, and my response might be to go over and shove somebody or chuck my milk in their face. When kids of color get into these types of altercations, adults in authority are often less inclined to understand the context of their actions. Instead, kids get labeled delinquent and sent to juvenile detention. Then they are on a whole other trajectory.

How has the coronavirus pandemic affected your clients?

DR. IGDA MARTINEZ: From the parents’ perspective, it’s overwhelming, especially if you have more than one child. 24-7 togetherness is hard on parents and couples. It’s hard for children to be out of school and cooped up with their parents and siblings. The entire fabric of society has been ripped, and we’ve seen an uptick in family conflict, family stress, verbal altercations and increased reports of violence in the home. Many of our clients who are homeless live in a one-bedroom or studio motel space. Whether you are a mom with or without a partner, the competing demands of children aren’t sustainable. Let’s say you have two or three — one in middle school who wants to be independent, and a child in elementary and a toddler. When the stay-at-home order was in effect and it wasn’t safe for families to go out, there was complete helplessness, hopelessness and frustration that impacted every aspect of care, including the ability to parent.

Since the pandemic began, parents have been urged to see to their own self-care. What does self-care look like for parents who are living in shelters or the one-room spaces at hotels used to house homeless families?

DR. IGDA MARTINEZ: This has been a major topic of conversation in our weekly behavioral health department meetings. The key is to support parents in a way that makes sense given their realities. It might be sensible to suggest getting out of the house for a walk, but if you are a person of color or transgender or any other identity that’s not traditionally considered part of the dominant, hegemonic norm, going out for a walk can be more dangerous than staying at home and being stressed. Also, some of our families live in areas with a lot of gun violence. So we talk a lot about suggestions of activities our patients can actually do. For some, that might mean going into the bathroom because that’s the only room in the home with a door that locks, splashing some water on your face, taking three deep breaths or looking in the mirror and doing a self-affirmation. It has to be things that are doable and relevant. If there isn’t a cultural match between our interventions and our clients’ realities, we’ll miss the mark. We want our clients to feel understood and heard.

What does it take to create an inclusive, supportive care environment?

DR. IGDA MARTINEZ: We used to be on a boat, but once we became land-based we chose a location that is accessible via public transportation. That removes one barrier. We also offer our patients free metrocards and roundtrip transport via our Good Health Shuttle. The shuttle has made a huge difference during the pandemic because riding public buses and the subway hasn’t felt safe. Our clinics are also warm and welcoming with multicultural references to make people feel safe and comfortable. Many of our patients have experienced multiple levels of trauma — multigenerational, physical, sexual, every type of trauma you can imagine. Our trauma-informed care model ensures that friendly staff members are there to explain to our clients where to go and what will happen next. The goal is to remove scary unknowns. Keeping our clients informed — reminding them of their next appointments, providing upfront explanations of the cost of services — is the way to treat people with care and respect. We take that very seriously. We also offer free delivery of prescriptions from our pharmacy to patients’ homes.

Has the uptick in urgency of demands for social justice — in health, education and politics — made you feel more hopeful?

DR. IGDA MARTINEZ: Absolutely. Historically, we’ve had moments with potential, but I’m hopeful that this time, the possibility for deep and meaningful impact will manifest as the change that’s needed. At the crux of all these issues is reinforcing people’s sense of self-worth. Experiencing microaggressions for years takes a toll on one’s thoughts, feelings, behavior, motivation and understanding of one’s rights. Ideally, your nuclear family and the environment in which you were raised gives you that self-esteem and sense of self-efficacy. A good school, where children spend most of their time, can also reinforce that. Going to the doctor should be self-affirming. It should be an experience that makes everyone feel “I have value. My body has value. I need to protect that. I deserve that. It’s a human right.”

Marion Hart

Lee Matz

Originally published on UNICEF USA as Why Coronavirus Is Hitting Black and Hispanic Children Especially Hard