Wisconsin’s Great Lakes communities expect to spend more than $245 million in five years to protect shorelines as a climate ‘tug of war’ drives extreme shifts in water levels.

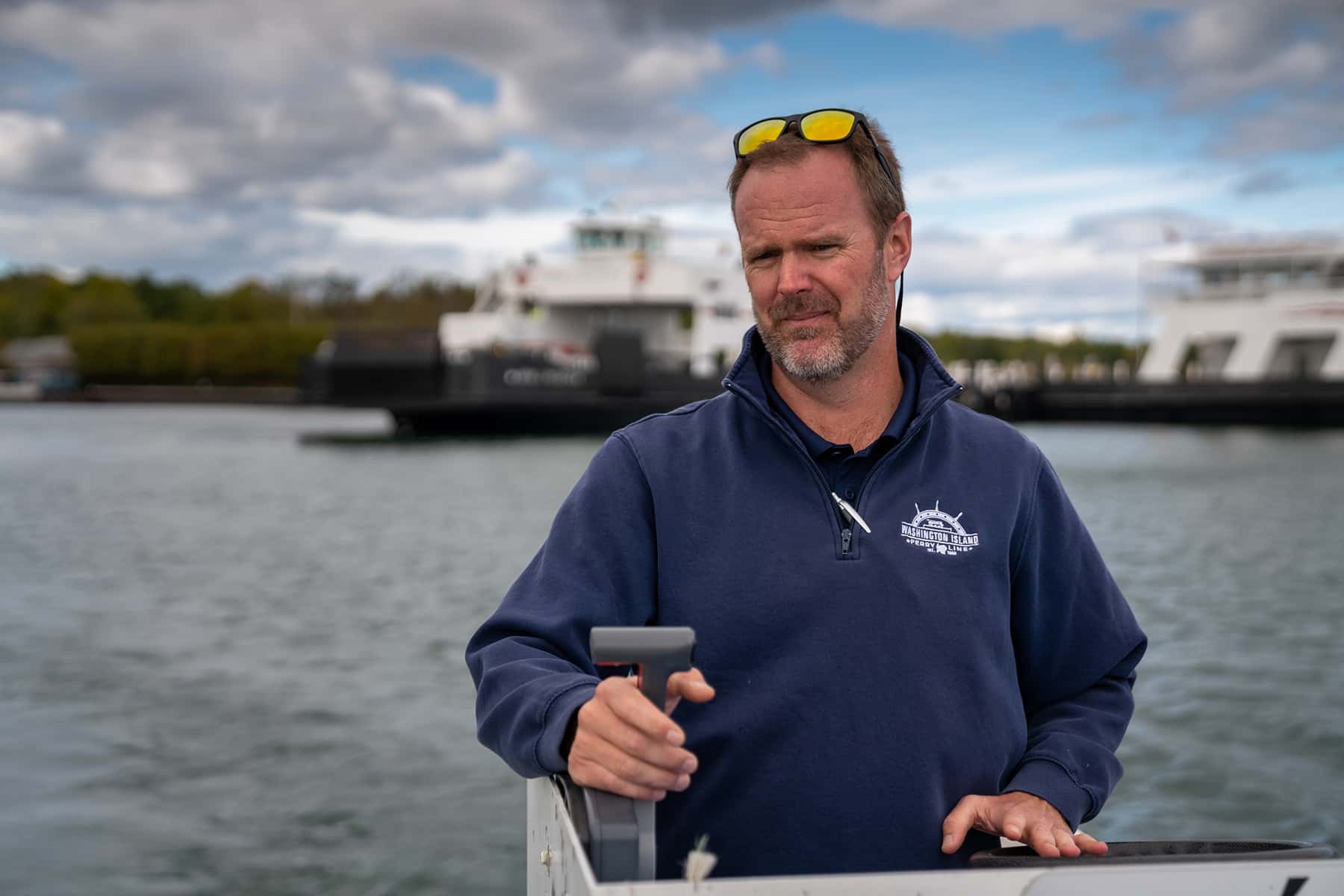

Mike Kahr, an engineer and owner of Death’s Door Marine, has watched Lake Michigan’s water levels fluctuate during his 40-plus year career. But even the veteran engineer hasn’t seen the lake’s water levels swing from low to high quite this rapidly.

Eight years ago, Kahr and his crew stayed busy dredging sand from the lake bottom so boats carrying passengers or heavy cargo could reach port. But as water levels surged to a record high last year, Kahr fielded call after call from property owners rushing to protect their shorelines by installing rocks and barriers to keep the waves from eroding their beaches — a flood of requests beyond what his crew could handle.

Some desperate property owners settled for less-experienced contractors who cut corners, he said. Kahr estimated that projects to fix that faulty work now make up about 20% of his workload.

Either way, the lake’s decade-long dance — from low to high water and now easing — has delivered plenty of business for Death’s Door Marine. But it’s not something Kahr celebrates.

“Yes, I make money at it. But I don’t like to take people’s money when the waves are lapping at their shoreline, and they’re taking money out of the retirement account,” he said.

Unlike the oceans, whose waters are rising as Earth’s steady warming melts glaciers, Great Lakes water levels largely depend on weather and are harder to predict. Lake Michigan’s levels have tended to fluctuate in cycles throughout its recorded history, swinging up or down roughly every three to 10 years.

Contractors, ferry boat captains, climate scientists and home owners call those ebbs and flows part of life along the Great Lake’s shoreline. But they are now living through the most dramatic shifts in their lifetimes.

Between record low waters in January 2013 and a record high in July 2020, Lakes Michigan and Huron collectively swung more than 6 feet, according to data from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The lakes have since dipped about a foot and a half, but remain above their long-term average. Climate scientists attribute the volatility to the interplay of the region’s rising temperatures and precipitation from more frequent and intense storms.

“It is affecting us in one way, shape, or form,” Kahr said of climate change. “It’s very scary to go from one extreme to the other in six and a half years.”

Low-water years require crews like Kahr’s to dredge waterways so boats can reach their destinations. But high water brings destructive storm surges that swallow beaches, swamp docks, erode lakeside bluffs and shutter businesses. Even winter’s storms can break loose frozen slabs, shoving ice into buildings or through the living rooms of lakeside homes.

The Great Lakes region will spend nearly $2 billion over the next five years combatting coastal damage exacerbated by climate change, according to a recent survey of 241 local governments by the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative, a coalition of 128 U.S. and Canadian mayors focused on protecting the Great Lakes. Wisconsin will bear an estimated burden of at least $245 million, said Sheboygan Mayor Ryan Sorenson, a board member of the coalition.

“When you live on the Great Lakes, you see high water and how this is impacting our community, and how it’s changed over generations,” Sorenson said. “Whether you think it’s cyclical, whether you think it’s climate change, folks in Sheboygan and Wisconsin understand that something needs to be done, regardless of your political affiliation.”

Climate scientists expect that extreme weather will only accelerate along the Great Lakes — driving even wilder fluctuations. Although lake levels have dipped from last year’s record, Sorenson and Kahr are among those calling for cities and property owners to urgently protect their shorelines, before the next lake surge brings more destruction.

Powerful Lake Michigan waters

On a windy late-September morning, the Washington Island Ferry rocked like an ocean liner in a squall. As the boat headed north through Death’s Door, an often turbulent passage between the mainland and Washington Island, waves crashed into its bow and mist spritzed passengers on its upper deck. In the distance to the east, past the abandoned lighthouse resembling the skeleton of a forgotten church, Lake Michigan’s waters stretched endlessly into the horizon.

The Great Lakes hold about 20% of theEarth’s surface freshwater. And Lake Michigan, the third-biggest Great Lake by surface area, stretches 118 miles across at its widest point — too far to see across. At its deepest point, more than 900 feet, the lake’s powerful waters would drown San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge with room to spare. The inland ocean holds 1.3 quadrillion gallons of water; its waves can sink ships, pulverize shoreline structures and carry fishermen out to its depths.

Hoyt Purinton, president of the Washington Island Ferry line and a seasoned captain, leads a fleet of five ships that navigate the waters off of Wisconsin’s Door County peninsula year-round — each big enough to carry about 150 passengers and 20 vehicles between the county’s mainland and its inhabited island to the north.

A thumb that juts into Lake Michigan, Door County boasts 300 miles of shoreline and is sometimes called the Cape Cod of the Midwest. Tourists flock to its beaches in the summer; come autumn, its sugar maples explode with orange and yellow. In 2020, despite the COVID-19 pandemic’s challenges, tourism generated nearly $400 million for the local economy.

Purinton, whose family has been in business for 80 years and lived in the area since before Wisconsin’s statehood, has faced a host of challenges from shifting lake levels in recent years. Low waters in 2013 forced the ferry to move operations to the island’s historic “Potato Dock,” which is surrounded by deeper waters. That move required dredging and cost his company up to $750,000.

High water in 2020 swamped parts of the Washington Island’s Ferry’s landing and the island, leaving captains to contend with floating debris. Water also flooded the dock at Rock Island, just east of Washington Island and a popular destination for campers. A submerged dock and pandemic-related health concerns forced the closure of Rock Island State Park much of last year, cutting into crucial state park system revenues, said Michael Bergum, who oversees nine state parks for the Wisconsin Department of Natural resources.

Purinton said he had never seen such a dramatic — and awe-striking — shift in Lake Michigan’s waters.

“It’s been a wild ride. It opens up your world view. It reminds you you’re not in charge,” he said. “The water always wins.”

Kahr says property owners and clients like Purinton should take action now — even with water dipping from its 2020 record. Docks need raising to accommodate coming water levels.

“Prepare for it so you can react in the future,” Kahr advises. “It’s much easier to do the work now than waiting until the water is lapping at the dock’s edge.”

A climate ‘tug of war’

Lake Michigan had experienced nearly 15 years of low water in 2013, when the Washington Island Ferry line moved its operations to deeper water.

Many assumed the trend would continue, and nobody predicted the lake’s dramatic rise in the following years, said Drew Gronewold, a University of Michigan associate professor of ecosystem science and management and expert on weather’s impact on the Great Lakes.

“In 2013, everyone was concerned about rising temperatures, loss of ice cover, and there was a narrative at that time that water levels are just going to continue to decline forever in light of climate change,” Gronewold said. “And then, at the beginning of 2014, something happened to the globe, literally a global scale phenomenon, which is the polar vortex. The cold Arctic air surrounding the top hemisphere — it wobbled, and it wobbled dramatically.”

That “wobbling” destabilized a band of Arctic air, sending south a blast of frigid air that parked over the Great Lakes region for weeks. Wind chills in Chicago dropped to minus 42 degrees, prompting one meteorologist to nickname the city, “Chiberia.”

The freeze thickened ice cover on the lakes, limiting evaporation. That unforeseen event set the stage for high water in the following years — along with intense rain and snow likely linked to Earth’s warming, Gronewold said.

More than a century of data from the Corps of Engineers show the cyclical fluctuation of waters in Lakes Michigan and Huron — measured together because the two bodies are connected at the Straits of Mackinac. Weather primarily drives the ebbs and flows. Precipitation boosts water levels, while evaporation — which increases with warmer temperatures — drops them.

The Great Lakes region is warming faster than elsewhere in the contiguous United States over the past century, according to a 2019 report by the Environmental Law and Policy Center. That’s tending to cause ice cover to form later in the year and lengthening the season for evaporation. Meanwhile, the region saw much more rain and snow, with more precipitation coming from “unusually large events,” like severe storms.

These two factors create an increasingly powerful “tug of war” effect that will likely bring more extreme shifts in lake levels, even on a year-to-year basis, Gronewold said.

“These two forces are opposite each other, and they are gaining strength as the climate changes,” Gronewold said.

Intense evaporation from 1998 to 2013 dramatically lowered the lakes, for instance. Waters then rose during the region’s subsequent “wettest five- to 10-year period in recorded history.”

Most models predict that temperatures and precipitation will continue to rise and bring extreme weather, Gronewald said.

Dramatic shifts in water levels on Lakes Michigan and Huron, as a result, will likely become increasingly common — even if average levels stay roughly the same, said Michael Notaro, associate director of University of Wisconsin-Madison’s Nelson Institute Center for Climatic Research.

Beyond speeding up coastal erosion, more frequent, intense storms bring heavier rains that increase the runoff of fertilizer into lakes, feeding algal blooms on nutrient-rich lakes that harm fish and other wildlife.

“It’s not really (a question of) when it’s going to happen. It’s already happening,” said Notaro.

Communities respond to rising water

Sorenson, who at 27 serves as Sheboygan’s youngest-ever mayor, grew up in the lakeside city of 48,000. Sometimes called the Malibu of the Midwest, Sheboygan is home to fleets of charter fishing boats, sandy beaches and surfers who brave its winter waters to catch frigid waves.

Sorenson remembers summer days he spent at the beach as a child, swimming, catching fish and building sand castles. And he remembers when rising waters began to wash those beaches away. Wanting to help home and business owners respond to lakeshore erosion is part of what inspired him to run for mayor, he said in a 2020 video announcing his candidacy.

“In the last few years, we’ve seen tremendously high water impact the business community on the boardwalk, where we’ve had to throw sandbags out there just to try to keep it at bay. And that’s not a long term solution for our community and how we address this issue,” he said.

“We’re seeing cliffs just getting washed away, falling into the lake. And I think something that we have to be truly concerned about is the long term impact that climate change has on our community.”

Great Lakes communities have spent $878 million in the past two years responding to coastal damage, according to the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative — a price tag that’s only expected to grow. Wisconsin’s expected $245 million in costs over the next five years is conservative, Sorenson said, because it doesn’t include every township or jurisdiction.

Shoreline erosion — and how to afford infrastructure improvements needed to protect against damage from high water — challenges urban centers and small towns along the Great Lakes.

Chicago, which rose atop a swamp along Lake Michigan’s southern shore, has endured destructive storms that have caused the lake to overflow its banks, flooded city streets, knocked out power and swamped basements — pointing out the need for infrastructure improvements or offshore breakwaters to protect neighborhoods.

In Door County, about an hour and a half north of Sheboygan, marina owners and village crews scrambled to rescue property, limit damage to piers and stack sandbags to protect the town’s buildings after November gales battered the village of Ephraim in 2019. After stones and debris washed onto the road at the south end of the village, the Wisconsin Department of Transportation added several hundred feet of protective rock alongside the highway to protect it from a future storm surge.

“That water definitely came up, and it came up quickly, to the point where we knew we had to do something,” said village administrator and harbormaster Brent Bristol, who helped lead a $358,000 project to rebuild a limestone wall and add more shoreline protection near Ephraim’s historic downtown.

Bristol and other village leaders sought to protect property while preserving the views and character of the village’s downtown, where visitors come to grab a cone from Wilson’s ice cream parlor and watch the sunset.

DNR analyzing Door County shores

The Wisconsin DNR has begun a strategic analysis of the Door Peninsula to inform leaders and other residents how to grapple with the extreme water level shifts along the peninsula.

“Changing water levels and storm events pose a significant challenge to the management of this coast,” reads the project’s page on the DNR’s website.

Prompting DNR’s analysis: a soaring tally of permitting requests from residents — not just to build barriers during high water years, but also to dredge during low-water years, said James Pardee, DNR environmental analysis and review specialist.

DNR aims to complete the analysis sometime next year. It will cover the “gamut of shoreline management,” including alternatives to permitting, funding and harbor management, Pardee said.

“We realized we needed to get a handle on how this is impacting people, how we respond to it, and what that could mean for the environment,” Pardee said.

The report may also inform public budgets, Pardee said.

Ephraim constructed its $358,000 shoreline project with cash on hand, instead of asking villagers to approve a bond. Bristol said Ephraim funded needed infrastructure projects with proceeds from Door County’s hotel room tax program. The Door County Tourism Zone Commission gets 70% of what’s collected to spend on marketing efforts that put “heads in beds,” said Bristol, but the rest comes back to municipalities, no strings attached.

Elsewhere, coastal erosion presents an unsustainable liability for local governments.

For Sheboygan, preparing for the future means reinforcing the city’s breakwater areas and adding protection for the shoreline, whether an additional seawall or protective layers of rock known as riprap, said Sorenson. It also means planting native vegetation, which stabilizes bluff slopes to help prevent future erosion.

But budgeting for those investments — while maintaining public services — is no small feat for a mid-sized city like Sheboygan, said the mayor. That’s why he hopes to secure federal and state aid.

In the Milwaukee County village of Fox Point, a $1.6 million Federal Emergency Management Agency grant, approved in August, will cover most of the $2.2 million the village needs to protect its eroding shoreline.

For the past two years, Fox Point has relied on stacked concrete blocks to absorb the impact of waves and protect against further erosion to a shoreline that has already receded as much as 12 feet in some areas — uprooting trees and clogging sewer pipes.

Sorenson says such grants could help Sheboygan and other Great Lakes cities collectively bolster their defenses against the volatile waters.

“Being the young mayor from Sheboygan, I can’t do this alone,” Sorenson said. “Whether it’s Sheboygan, Racine, Sturgeon Bay, Green Bay, Marinette, Milwaukee, and everywhere in between, we need to have a clear focus in terms of how we address this.”

Mario Koran

Brett Kosmider, Dan Eggert, Coburn Dukehart, and Tad Dukehart

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.