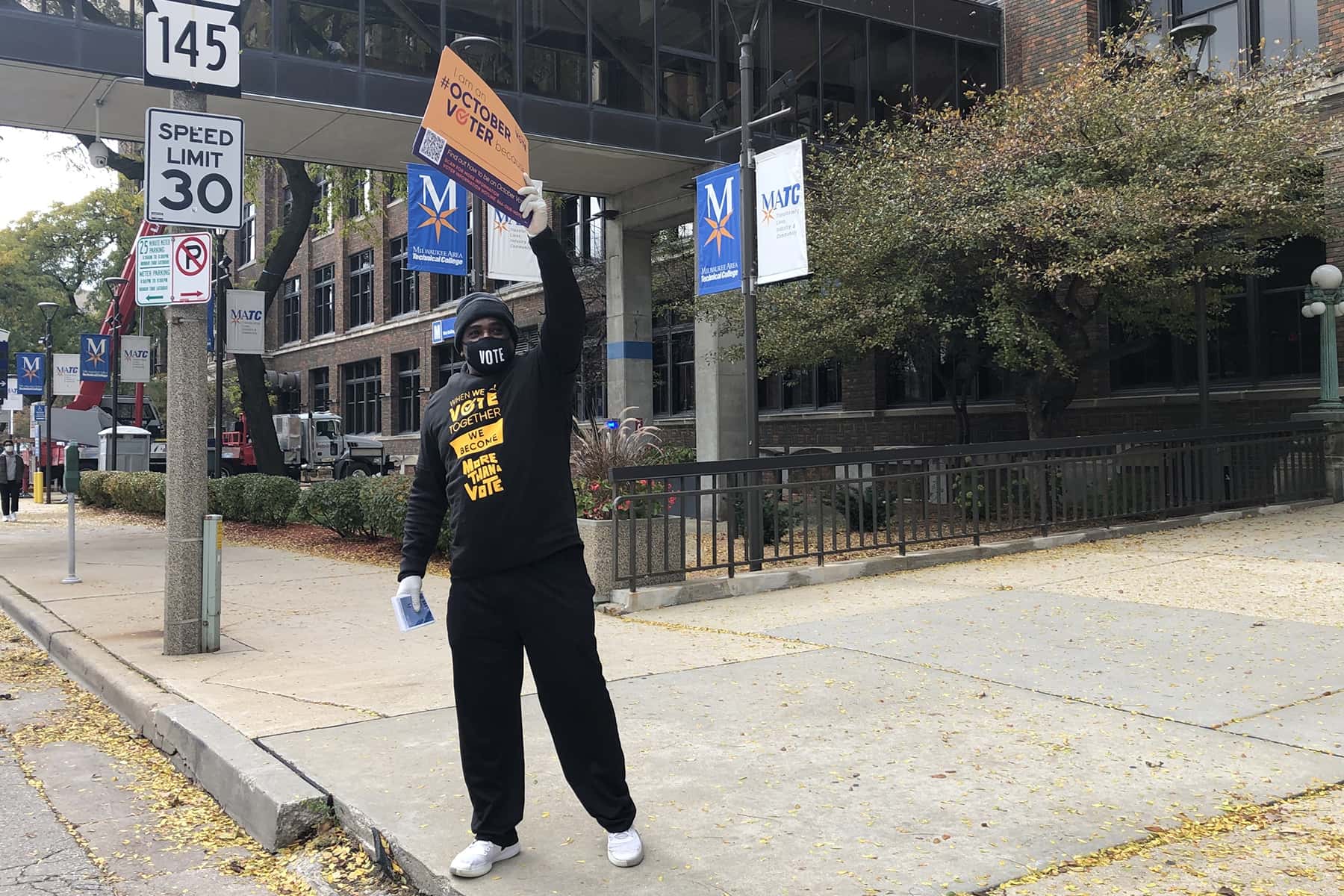

Working digitally and on the streets of Milwaukee, activists tried to convince nonvoters to go to the polls, but distrust and disgust kept some away.

When Angela Lang reflected on the thousands of conversations she and other members of her community organization, BLOC, have had with Milwaukee residents, one floats to the top of her mind. It was with a 54-year-old Milwaukee resident who explained to Lang’s colleague that she was not voting because she was a convicted felon. Unbeknownst to her, she had been eligible for about 12 years — since she completed her probation. A BLOC staffer was the first to tell her she could, in fact, vote.

“It’s bittersweet,” Lang said. “I think it’s incredibly powerful that we’re the ones to tell people when their voting rights have been restored. It’s also very frustrating that it took that long and people didn’t know until we had to talk to them.”

There are a variety of reasons people don’t vote, including criminal convictions, antipathy about politics and government, confusion about which candidate was best, or not liking any of them.

Regardless of their rationale, people who don’t vote are potentially as powerful, or even more so, than any other bloc in the electorate. Although the November general election saw high turnout in Wisconsin and broke a record nationwide, 1.2 million eligible voters in the state and 79.6 million across the nation didn’t cast ballots. In a state where 20,682 votes propelled President-elect Joe Biden to a win, a small fraction of those nonvoters could have shifted the outcome.

Organizers fight to raise turnout

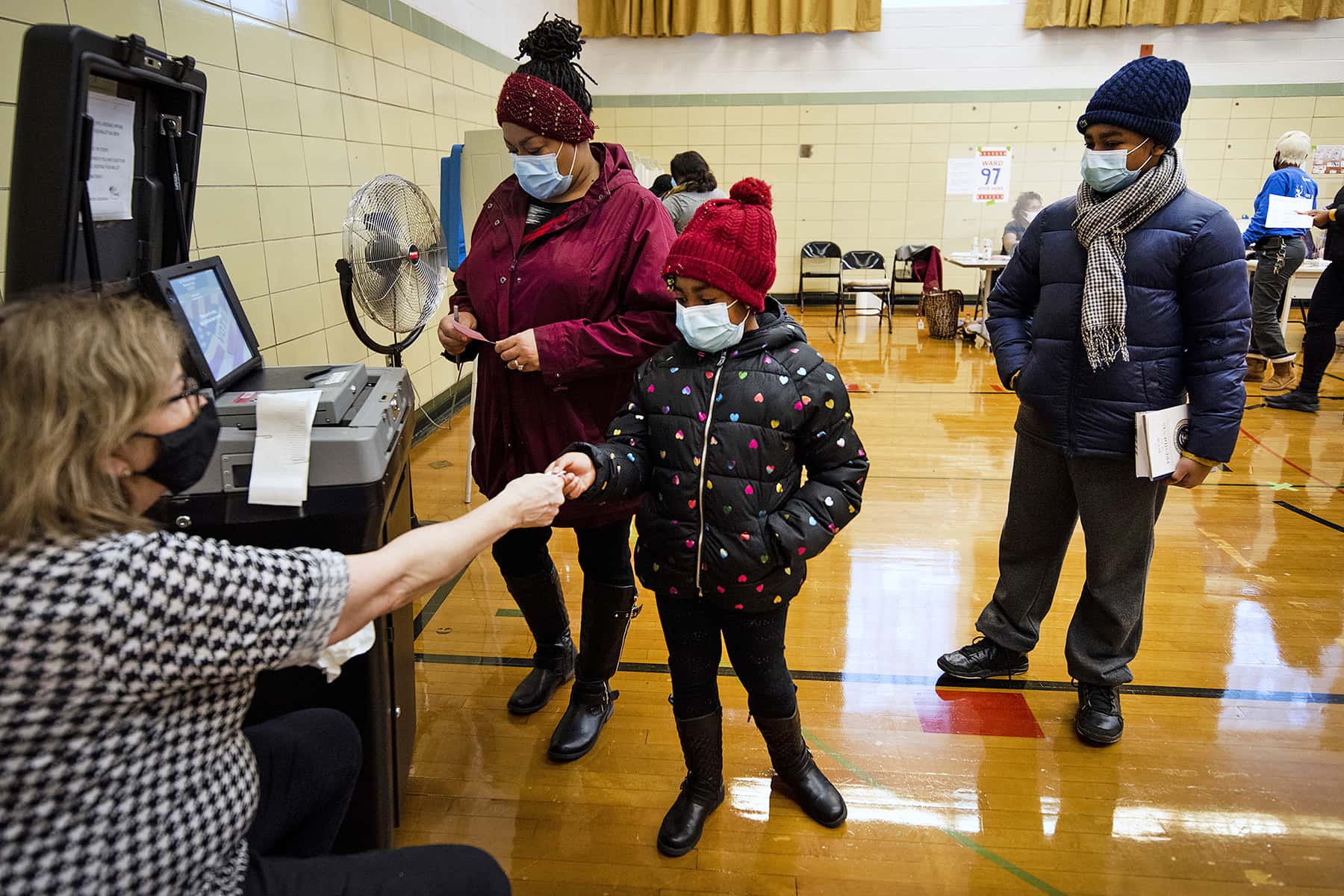

In Milwaukee, organizers said the already tough task of convincing people to vote was even more difficult this year because of the pandemic and concerns about potential voter intimidation or acts of violence at polling places.

“All of these things would have and should have served to really significantly depress participation and turnout, and we didn’t see that happen. And the reason why we didn’t see that happen is because these community organizations stepped in and filled in the gap,” said Jennifer Epps-Addison, network president of the Center for Popular Democracy, a progressive organization the pushes for a “pro-worker, pro-immigrant, racial and economic justice agenda.”

While Wisconsin had the second highest statewide turnout on record, Milwaukee’s vote totals were nearly identical in 2020 to the 2016 election. The city, which was under a microscope during the partial recount instituted by President Donald Trump’s campaign, was where nearly 70 percent of Wisconsin’s Black residents live.

“Immense” barriers keep many people from voting, she said, especially people of color, who are disproportionately affected by strict voter ID laws. Even during the pandemic, when voters widely viewed absentee voting as a safer option than voting in person, Black people had reason to distrust this method. Their absentee ballots have historically been rejected at a higher rate than those of white voters.

Another barrier: Some groups, such as BLOC, transitioned to digital canvassing in light of a surge of coronavirus cases in the city. This meant face-to-face conversations, such as those with the 54-year-old woman who thought she was ineligible to vote, were not happening. Forgoing door-to-door canvassing was a difficult decision for Lang, but she felt it was necessary to protect her team members and those they serve.

“Everyone at our organization is Black; we’re targeting the North Side of Milwaukee. And we know that the Black, brown and indigenous communities are the most disproportionately impacted by COVID,” she said.

The city of Milwaukee has had 54,037 coronavirus cases and 488 deaths. Nationwide, Black people are dying from COVID-19 at nearly two times the rate of white people.

Disillusionment leads to low turnout

The pandemic was not the only reason for depressed turnout, organizers say. One of the most common complaints that Lang and her team hear Milwaukee’s infrequent voters express was that politicians do not stick to their promises.

“I think a lot of times, people just don’t feel that some elected officials are working in their interests, or we’ve seen sometimes that candidates will say whatever they need to say in order to get elected,” Lang said.

Epps-Addison said many voters in Milwaukee did not trust either major party presidential candidate.

“The conversations that we had with people on the ground were difficult, not because people didn’t understand that a lot was that stake or that a lot is wrong, but that they really just didn’t believe either of the candidates had their best interests at heart,” Epps-Addison said.

She cited Biden’s authorship of the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act — which was blamed for the current high incarceration rate of Black people in the United States — as a major deterrent for some Milwaukee residents of color, a city that votes overwhelmingly Democratic.

Convincing voters to choose a particular candidate was not her group’s goal, she added. “We are really organizing to build a system that is worthy of our people, that our people believe in because it actually works for them.”

A February 2020 study of 12,000 “chronic non-voters” by The Knight Foundation showed that 38% of respondents believed elections do not represent the will of the people. While people who vote infrequently or never vote are labeled as lazy, apathetic or poorly educated, Lang said it was essential to take their concerns seriously, because they’re often rooted in lived experiences.

“I think what’s really important is to acknowledge that all of that is legitimate,” she said, adding that it is essential to “show how people are able to intervene and interject in a political system that doesn’t always feel like it’s designed for us to participate in.”

That was why BLOC emphasizes year-round engagement with residents, so they can start to see that participation in the political process can make a difference in local government decisions that affect their community, not just in general elections.

“I think that nobody has ever been shamed into voting or into supporting or changing their political beliefs,” said Epps-Addison. “Shame is not the thing that is going to motivate voters.”

Turnout down in communities of color

While the number of eligible voters who did not cast ballots in Milwaukee stayed steady from 2016 to 2020, turnout in predominantly Black wards decreased. Across the city of Milwaukee, 39% of eligible voters did not vote in 2020, virtually the same as in 2016. The number of nonvoters increased slightly from 158,035 nonvoters in 2016 to 159,051 this election year.

Of the 28 wards where turnout dropped by at least 10 percentage points, 17 of them were wards in which Black people made up at least 80% of the estimated citizen, voting-age population.

In Wisconsin, it was most accurate to measure turnout based on the percentage of eligible voters, not registered voters, because same-day registration makes such comparisons inaccurate. In a typical year, 10% to 15% of Wisconsin voters register or update their registration on Election Day, according to the Wisconsin Elections Commission. Same-day registration data for the 2020 general election won’t be available until January.

Reaching nonvoters through deep conversations

As David Fleischer sees it, those who typically do not vote hold immense power. In fact, the director of the Los Angeles Leadership LAB dedicated his organization to engaging this bloc during door-to-door outreach this election cycle.

His team uses a technique called “deep canvassing” to try to convince nonvoters to cast a ballot. While traditional canvassing typically was a transactional exchange of information, deep canvassing shifts the emphasis to getting into a substantive and emotional conversation with the potential voter.

The organization previously used this technique to engage with people who voted for Proposition 8, a measure that banned same-sex marriage in California, and try to change their minds. This year, Fleischer and his colleagues thought their efforts were best used focusing on turning a nonvoter into a voter. The group had members on the ground in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, North Carolina and Ohio this year.

Fleischer’s strategy was simple: Center the conversation around love. After easing into a conversation with the potential voter, he asks people about their thoughts on voting. Then, he transitions into telling a story about someone he loved.

“For me, voting is political, of course, but it’s also personal,” Fleischer tells the person. “I think about the people I love. And today I’m thinking about my dad who died in January.”

By connecting the relationship with a loved one to the value of voting, Fleischer encourages folks to see their vote as meaningful. His organization’s goal wasn’t just to encourage people to vote — it was to get them to vote against Trump. By talking to voters about how he thinks Trump was untrustworthy and a poor leader for the country, he hoped to convince them that a vote against Trump was a vote for love.

While many campaigns focused on digital interaction with voters during the pandemic — and reached millions online — Fleischer said personal interaction was more effective, even if it means reaching fewer people.

“Really, a more honest way to look at it is, would you rather attempt or intend to communicate with millions? Or would you rather actually communicate with some smaller number? And, to me, actual communication is actually what’s relevant,” Fleischer said.

How effective was this strategy? The metrics, he said, are not in yet.

Nonvoters: from ‘pessimists’ to ‘doers’

Just like voters, nonvoters have different motivations. A 2012 study by Ellen Shearer, professor at Northwestern University’s Medill School of Journalism and co-author of “Nonvoters: America’s No-Shows,” identified six subgroups.

The largest group, “the pessimists,” are often conservative-leaning and have a general feeling that the country was going down the wrong track. The smallest subgroup, ”the doers,” are media savvy and educated but feel removed from Washington politics. Other groups include the “too busys” — working or retired women whose schedules make it difficult to find time to vote — and the “tuned outs” — young people who are apathetic toward politics.

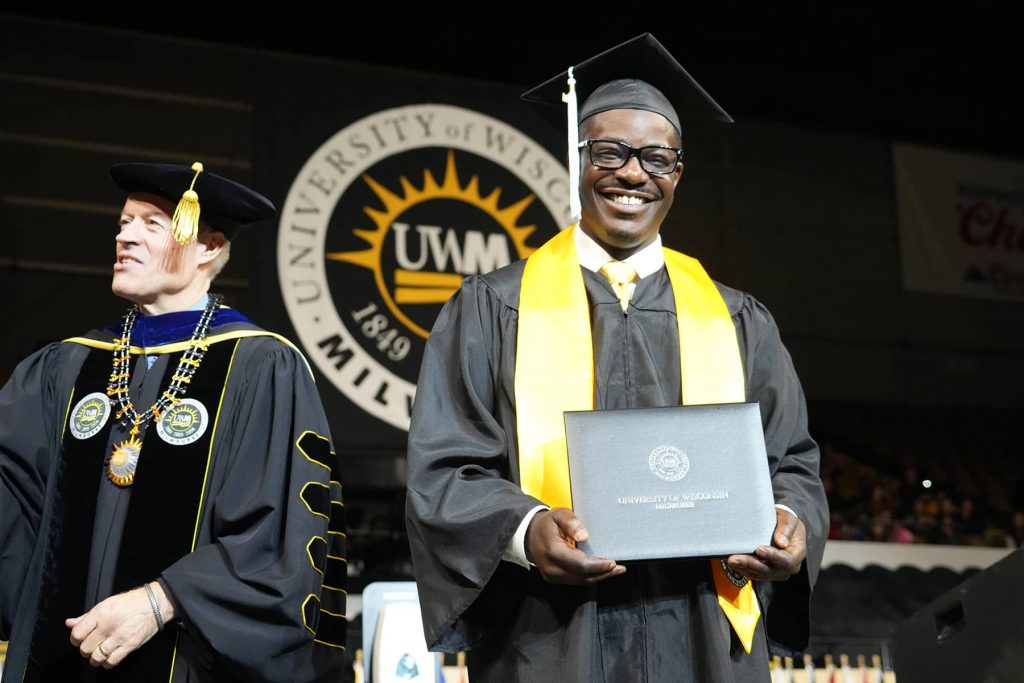

Northwestern professor Jack Doppelt, co-author of “Nonvoters,” added that while nonvoters and voters are a lot alike, one factor that separates them was education.

Nonvoters are twice as likely to have a high school degree or less. Just over half of nonvoters have that level of education compared to about one-fourth of people who do vote, according to the recent NPR/Ipsos/Medill poll. Nonvoters also tend to be younger, less affluent, and if they were to vote, would split almost evenly Democratic and Republican.

“Generally speaking,” Doppelt said, “there’s very little difference in how voters and nonvoters are going to vote.”

For 38-year-old Alishia Abarca, it was a question of money. She thinks with all of the lobbyists and corporations influencing politics, the system will ensnare any respectable person who enters it. She has never voted.

“With every good intention that anybody goes into politics with, they at the end of it will be corrupt. No matter what. Even if I went into politics … guess what. Money is powerful,” Abarca said. She was one of the respondents surveyed in the NPR/Ipsos/Medill poll.

Abarca has two sons, including a 19-year-old who was ill and has a child. She was struggling to feed her younger son on her income as a personal care assistant. Abarca lives in Superior, Wisconsin, and has considered moving to Canada because of her distrust of America’s government and frustration with its health care system. Still, she’s not certain she would vote there.

There was one thing that could change her mind: if candidates agreed to take a pay cut and make the salary she does. By walking in her shoes, she said, they then might understand the struggles of so many Americans.

On the whole, nonvoters appear to be a stubborn crowd. A selection of nonvoters was asked what could convince them to cast their ballot, there was one answer that reigned supreme: “Nothing.”

Nora Eckert

Angela Major, Darren Hauck, and Nora Eckert

The nonprofit Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism collaborates with Wisconsin Public Radio, Wisconsin Public Television, other news media and the UW-Madison School of Journalism and Mass Communication. All works created, published, posted or disseminated by the Center do not necessarily reflect the views or opinions of UW-Madison or any of its affiliates.