By Kwasi Konadu, Professor in Africana & Latin American Studies, Colgate University; and Clifford C. Campbell, Visiting Lecturer, Dartmouth College

The 13th Amendment is having a moment of reckoning. Considered one of the crowning achievements of American democracy, the Civil War-era constitutional amendment set “free” an estimated 4 million enslaved people and seemed to demonstrate American claims to equality and freedom. But the amendment did not apply to those convicted of a crime.

And one group of people are disproportionately, though not solely, criminalized – descendants of formerly enslaved people.

“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude,” the amendment reads, “except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

In other words, slavery still exists in America, but the only people whose labor can be enslaved are those convicted of a crime.

To some lawmakers and human rights advocates, that exception is a blight on democracy and the very idea of freedom – even for those convicted of a crime. As scholars of slavery and the histories of African America, our research shows the 13th Amendment’s exception clause reinvented slave labor and involuntary servitude behind prison walls.

Free labor

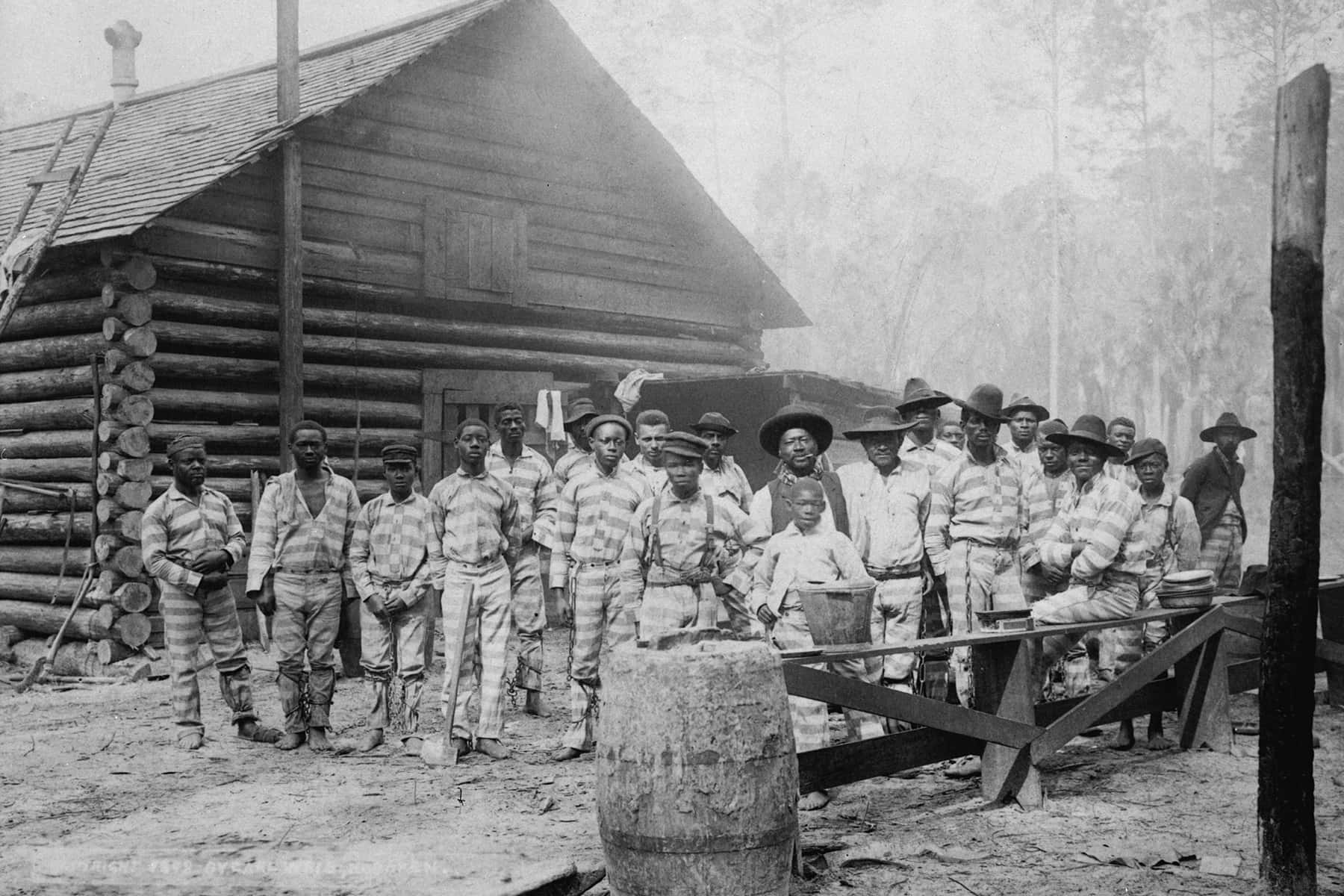

Since the late 1700s, American states have used the labor of convicts, a predominantly white institution that came to include people of African ancestry. Convict slavery and chattel slavery co-existed. In Virginia, the state that had the largest number of enslaved Africans, inmates were declared “civilly dead” and “slaves of the State.”

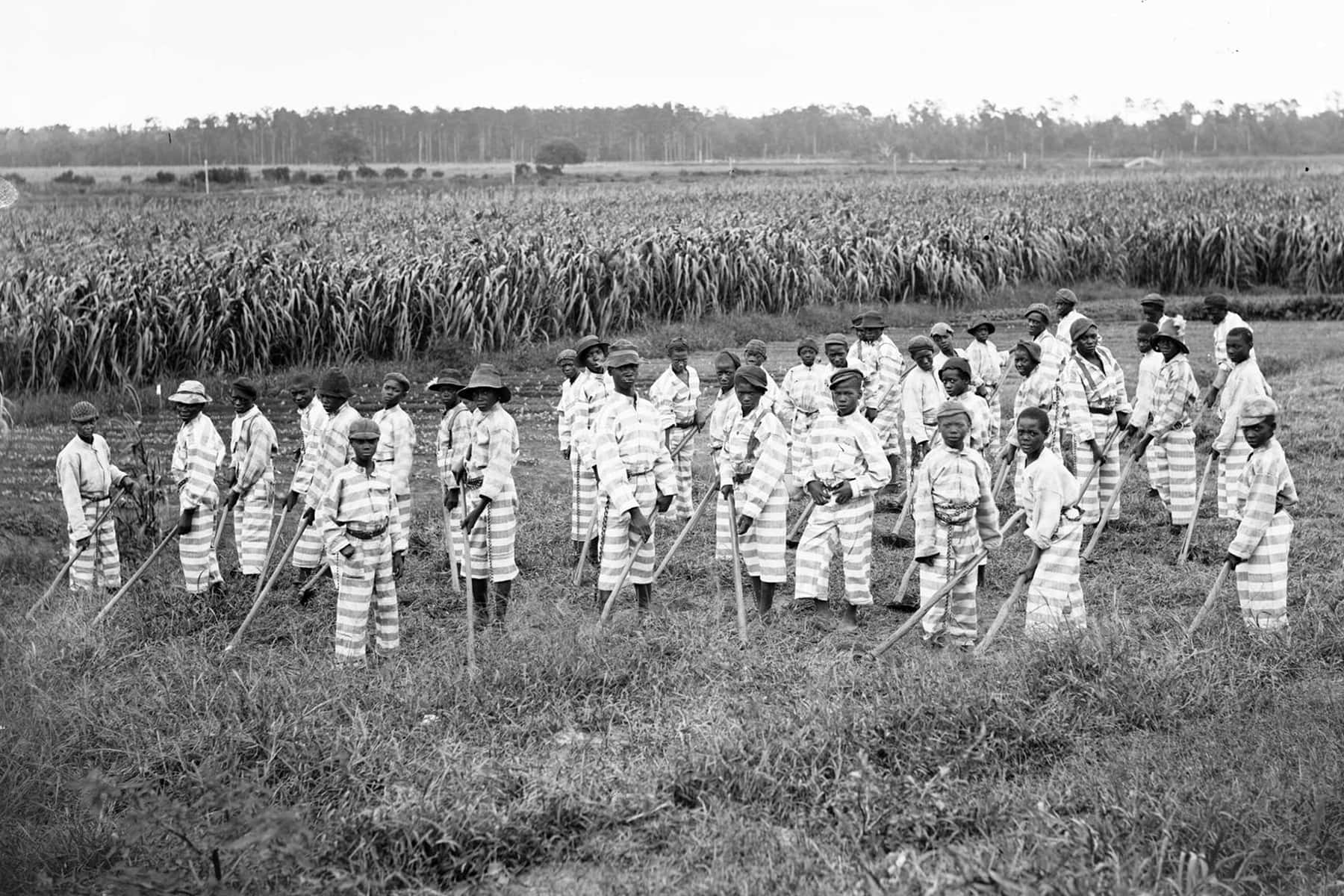

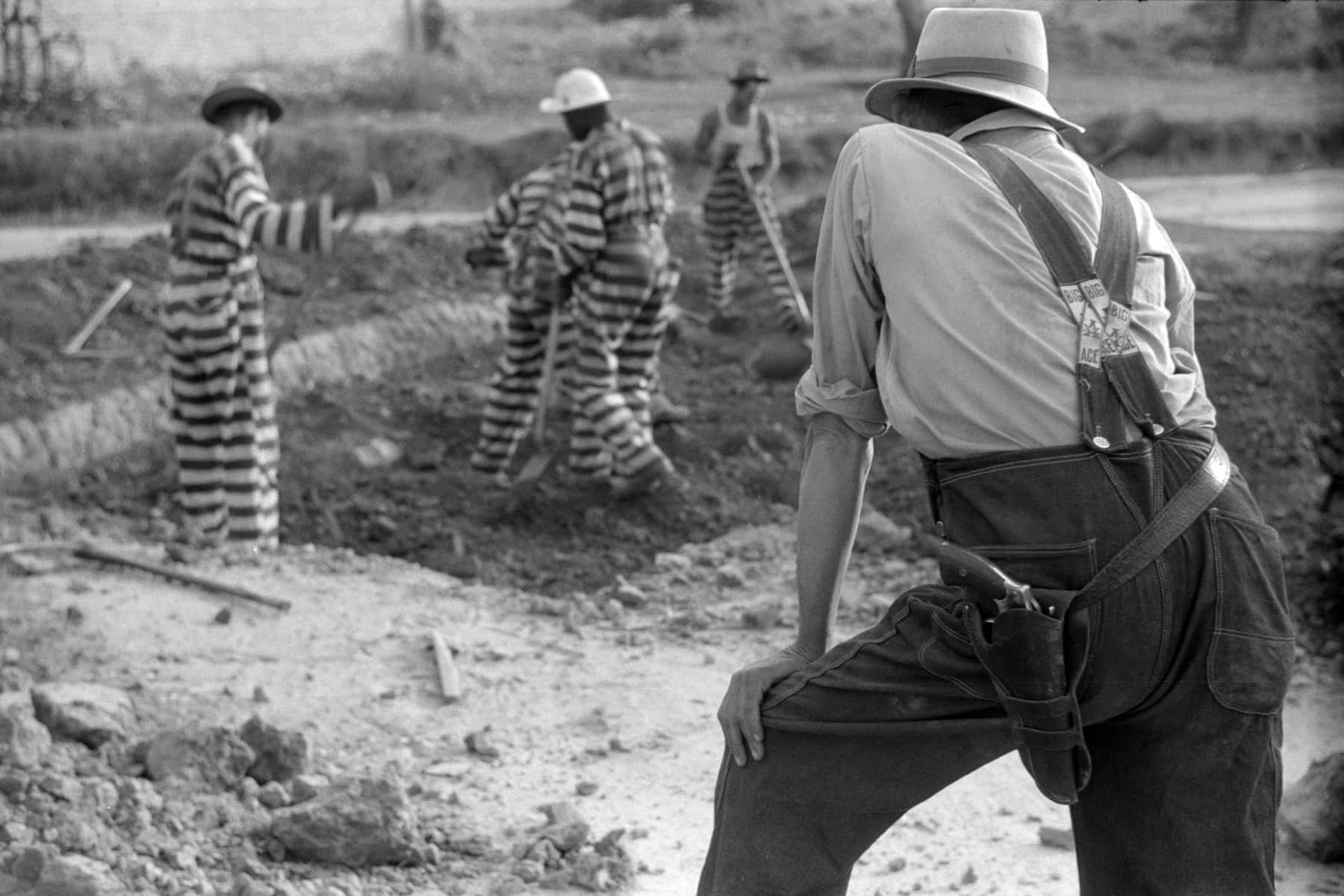

It was not until the early 1900s that states ended convict-leasing, the practice whereby wealthy farms or industrial business owners paid state prisons to use inmates to work on railroads and highways and in coal mines. In Georgia, for example, the end of convict-leasing in 1907 caused severe economic blows to several industries, including brick and mining companies and coal mines. Without access to cheap labor, many collapsed or suffered severe losses.

Today, the United States has the largest prison population in the world, with an estimated 2.2 million incarcerated people. For many of them, the 13th amendment’s exception has become a rule of forced labor. Over 20 states still include the exception clause in their own state constitutions. Thirty-eight states have programs in which for-profit companies have factories in their prisons. Prisoners perform everything from picking cotton to manufacturing goods to fighting forest fires.

In a 2015 story, “American Slavery, Reinvented,” The Atlantic magazine described the consequences of refusing to work. “With few exceptions,” wrote the story’s author, Whitney Benns, “inmates are required to work if cleared by medical professionals at the prison. Punishments for refusing to do so include solitary confinement, loss of earned good time, and revocation of family visitation.”

In some cases, inmates are paid less than a penny an hour. And many who served their sentences leave prison in debt, having worked without the protections of the Fair Labor Standards Act or the National Labor Relations Act.

In Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana and Texas, penal plantations exist where predominantly Black men pick cotton and other crops under the watchful eyes of typically armed white men on horseback. Some of the largest cotton production prisons are in Arkansas, helping to make the United States “the third-largest producer of cotton globally,” behind China and India.

Ironically, many of the prisons, like Louisiana State Penitentiary, or “Angola,” are located on former slave plantations.

Modern-day convict slavery

Late in 2021, on the 156th anniversary of ratification of the 13th Amendment of December 6, 1865, U.S. Senator Jeff Merkley, an Oregon Democrat, introduced a bill to eliminate the exception. Known as the Abolition Amendment, the resolution would “prohibit the use of slavery and involuntary servitude as a punishment for a crime.”

“America was founded on beautiful principles of equality and justice and horrific realities of slavery and white supremacy,” Merkley said in a statement, “and if we are ever going to fully deliver on the principles, we have to directly confront the realities.”

Based on our research, those realities are steeped in the mythology that America is a “land of the free.” While many believe it is the freest country in the world, the nation ranks 23rd among countries that uphold personal, civil and economic freedoms, according the Human Freedom Index, co-published by the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C.

For U.S. analysts who examine the nation’s constitutional pledges and its actions, the country is less free than often assumed.

Over time, those realities demonstrate a conflict in U.S. history, illustrated by the 13th Amendment. Some states approved the amendment in 1865. Others, like Delaware, Mississippi and New Jersey, rejected it. Free labor was at stake. America embraced the idea of freedom, but it was economically powered by slave labor. Today, the net result is that America is a nation with “4 percent of the planet’s population but 22 percent of its imprisoned,” according to Bryan Stevenson writing in The New York Times Magazine.

Some readers might be puzzled by our discussion of “slavery” in modern life. The Slavery Convention was an international treaty created in 1926, and it defined slavery as “the status or condition of a person over whom any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership is exercised.” The “right of ownership” includes buying, selling, using, profiting, transferring or destroying that person. This legal definition of slavery has been upheld by international courts since 1926.

The U.S. government ratified this treaty in 1929. But in doing so it opposed “forced or compulsory labour except as punishment for crime of which the person concerned has been duly convicted,” according to the treaty. The wording of the U.S. government’s opposition is the same as the 13th Amendment. Sixty-four years after passing that amendment, the U.S. government affirmed the use of prisons for forced labor or convict slavery.

It is, then, unlikely the Abolition Amendment will become law despite the authority to do so granted by the second section of the 13th Amendment. A constitutional amendment would have to pass both the House and Senate by a two-thirds majority, then be ratified by three-quarters (or 38) of the 50 state legislatures.

Interest by lawmakers in abolishing modern-day slavery is nothing new.

Back in 2015, President Barack Obama issued a proclamation to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the 13th Amendment’s passage. He praised the amendment for “the protections it restored and the lives it liberated,” but then conceded work still needed to be done to fully abolish all forms of slavery.

The interest in the 13th Amendment has also been widespread throughout popular culture. Films, books, activists and prisoners across the United States have for some time linked that amendment to what legal scholar Andrea Armstrong calls “prison-created slavery.”

But given the political realities and economic imperatives at play, free prison labor will persist in America for the foreseeable future, leaving in serious doubt the idea of American freedom – and abundant evidence of modern-day convict slavery.

Library of Congress

Originally published on The Conversation as The 13th Amendment’s fatal flaw created modern-day convict slavery

Support evidence-based journalism with a tax-deductible donation today, make a contribution to The Conversation.