Sometime over the summer, if Vladimir Putin can be believed, Russia moved some of its short-range nuclear weapons into Belarus, closer to Ukraine and onto NATO’s doorstep.

The declared deployment of the Russian weapons on the territory of its neighbor and loyal ally marks a new stage in the Kremlin’s nuclear saber-rattling over its invasion of Ukraine and another bid to discourage the West from increasing military support to Kyiv.

Neither Putin nor his Belarusian counterpart, Alexander Lukashenko, said how many were moved — only that Soviet-era facilities in the country were readied to accommodate them, and that Belarusian pilots and missile crews were trained to use them.

The U.S. and NATO haven’t confirmed the move. NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg denounced Moscow’s rhetoric as “dangerous and reckless,” but said in July the alliance has not seen any change in Russia’s nuclear posture.

While some experts doubt the claims by Putin and Lukashenko, others note that Western intelligence might be unable to monitor such movement.

In early July, CNN quoted U.S. intelligence officials as saying they had no reason to doubt Putin’s claim about the delivery of the first batch of the weapons to Belarus and noted it could be challenging for the U.S. to track them.

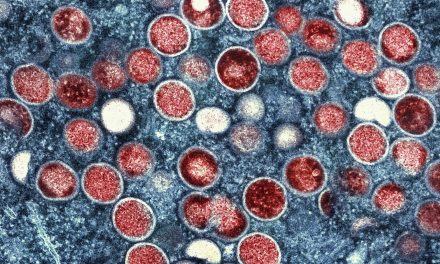

Unlike nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missiles that can destroy entire cities, tactical nuclear weapons for use against troops on the battlefield can have a yield as small as about 1 kiloton. The U.S. bomb in Hiroshima in World War II was 15 kilotons.

The devices are compact: Used on bombs, missiles and artillery shells, they could be discreetly carried on a truck or plane. Aliaksandr Alesin, an independent Minsk-based military analyst, said the weapons use containers that emit no radiation and could have been flown into Belarus without Western intelligence seeing it.

“They easily fit in a regular Il-76 transport plane,” Alesin said. “There are dozens of flights a day, and it’s very difficult to track down that special flight. The Americans could fail to monitor it.”

Belarus has 25 underground facilities built during the Cold War for nuclear-tipped intermediate-range missiles that can withstand missile attacks, Alesin said. Only five or six such depots could actually store tactical nuclear weapons, he added, but the military operates at all of them to fool Western intelligence.

Early in the war, Putin referenced his nuclear arsenal by vowing repeatedly to use “all means” necessary to protect Russia. He has toned down his statements recently, but a top lieutenant continues to dangle the prospect with terrifying ease.

Dmitry Medvedev, the deputy head of Russia’s Security Council who served as a placeholder president in 2008-12 because Putin was term-limited, unleashes near-daily threats that Moscow won’t hesitate to use nuclear weapons.

In a recent article, Medvedev said “the apocalypse isn’t just possible but quite likely,” and the only way to avoid it is to bow to Russian demands.

The world faces a confrontation “far worse than during the Cuban missile crisis because our enemies have decided to really defeat Russia, the largest nuclear power,” he wrote.

Many Western observers dismiss that as bluster. Putin seems to have dialed down his nuclear rhetoric after getting signals to do so from China, said Keir Giles, a Russia expert at Chatham House.

“The evident Chinese displeasure did have an effect and may have been accompanied by private messaging to Russia,” Giles told The Associated Press.

Moscow’s defense doctrine envisages a nuclear response to an atomic strike or even an attack with conventional weapons that “threaten the very existence of the Russian state.” That vague wording has led some Russian experts to urge the Kremlin to spell out those conditions in more detail and force the West to take the warnings more seriously.

“The possibility of using nuclear weapons in the current conflict mustn’t be concealed,” said Dmitry Trenin, who headed the Moscow Carnegie Center for 14 years before joining Moscow’s state-funded Institute for World Economy and International Relations.

“The real, not theoretical, perspective of it should create stimuli for stopping the escalation of the war and eventually set the stage for a strategic balance in Europe that would be acceptable to us,” he wrote recently.

Western beliefs that Putin is bluffing about using nuclear weapons “is an extremely dangerous delusion,” Trenin said.

Sergei Karaganov, a top Russian foreign affairs expert who advises Putin’s Security Council, said Moscow should make its nuclear threats more specific in order to “break the will of the West” and force it to stop supporting Ukraine as it seeks to reclaim Russian-held areas in a grinding counteroffensive.

“It’s necessary to restore the fear of nuclear escalation; otherwise mankind is doomed,” he said, suggesting Russia establish a “ladder” of accelerating actions.

Deploying nuclear weapons in Belarus was the first step, Karaganov said, with perhaps a follow-up of warning ethnic Russians in countries supporting Ukraine to evacuate areas near facilities that could be nuclear targets.

If that doesn’t work, Karaganov suggested a Russian nuclear strike on Poland, alleging Washington wouldn’t dare respond in kind to protect a NATO ally, for fear of igniting a global war.

“If we build the right strategy of intimidation and even the use of it, the risk of a retaliatory nuclear or any other strike on our territory could be reduced to a minimum,” he said. “Only if a madman who hates his own country sits in the White House would America risk to launch a strike ‘in the defense’ of the Europeans and draw a response, sacrificing Boston for Poznan.”

The Moscow-based Council of Foreign and Defense Policies, a panel of leading military and foreign policy experts that includes Karaganov, denounced his comments as “a direct threat to all of mankind.”

While pro-Kremlin analysts floated such scenarios, Lukashenko, the Belarusian leader, says hosting Russian nuclear weapons in his country is meant to deter aggression by Poland.

He claimed a number of nuclear weapons were flown to Belarus without Western intelligence noticing, with the rest coming later this year. Officials in Moscow and Minsk said the warheads could be carried by Belarusian Su-25 ground attack jets or fitted to short-range Iskander missiles.

Giles, of Chatham House, said the deployment was about “cementing Putin’s control over Belarus” and did not offer Moscow any military advantage over placing them in Russia’s Baltic exclave of Kaliningrad that borders Poland and Lithuania.

The West should recognize this as a ploy “that has far more to do with Russia’s ambitions for Belarus than any genuine impact on European security beyond that,” Giles said.

Some observers question whether the deployment to Belarus has even happened.

Miles Pomper, a senior fellow at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute, challenged Lukashenko’s claim that nuclear weapons were covertly flown to Belarus. They are normally moved by rail, he said, and there are no signs of “the support elements that you would see that would go with shipments of weapons.”

Others note Russia could have deployed the weapons without adhering to protocols used in the 1990s, when Moscow wanted to show the West its nuclear arsenal was secure amid economic and political turmoil.

Belarusian military analyst Valery Karbalevich said keeping such details secret could be a Kremlin strategy of “applying permanent pressure and blackmailing Ukraine and the West. The unknown scares more than certainty.”

Alesin, the Minsk-based analyst, argued that U.S. and NATO may play down the deployment of nuclear weapons to Belarus because they pose a threat the West finds difficult to counter.

“The Belarusian nuclear balcony will hang over a large part of Europe. But they prefer to pretend that there is no threat, and the Kremlin is just trying to scare the West,” he said.

If Putin decides to use nuclear weapons, he may do it from Belarus in hopes that a Western response would target that country instead of Russia, Alesin said.

The political opposition to Lukashenko warns that such a deployment turns Belarus into a hostage of the Kremlin.

While Lukashenko sees such weapons as a “nuclear umbrella” protecting the country, “they turn Belarus into a target,” said exiled opposition leader Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who tried to unseat the authoritarian leader in a 2020 election widely viewed as fraudulent.

“We are telling the world that preventative measures, political pressure and sanctions are needed to resist the deployment of nuclear weapons to Belarus,” she said. “Regrettably, we haven’t seen a strong Western reaction yet.”