Nearly seventeen years ago my mentor Dr. James Cameron returned from a trip to the Senate chambers when they issued an apology for never passing an anti-lynching bill. As a lynching survivor and creator of America’s Black Holocaust Museum, he was center stage as the Senate did something to “make up” for never passing a federal law to make lynching a federal crime.

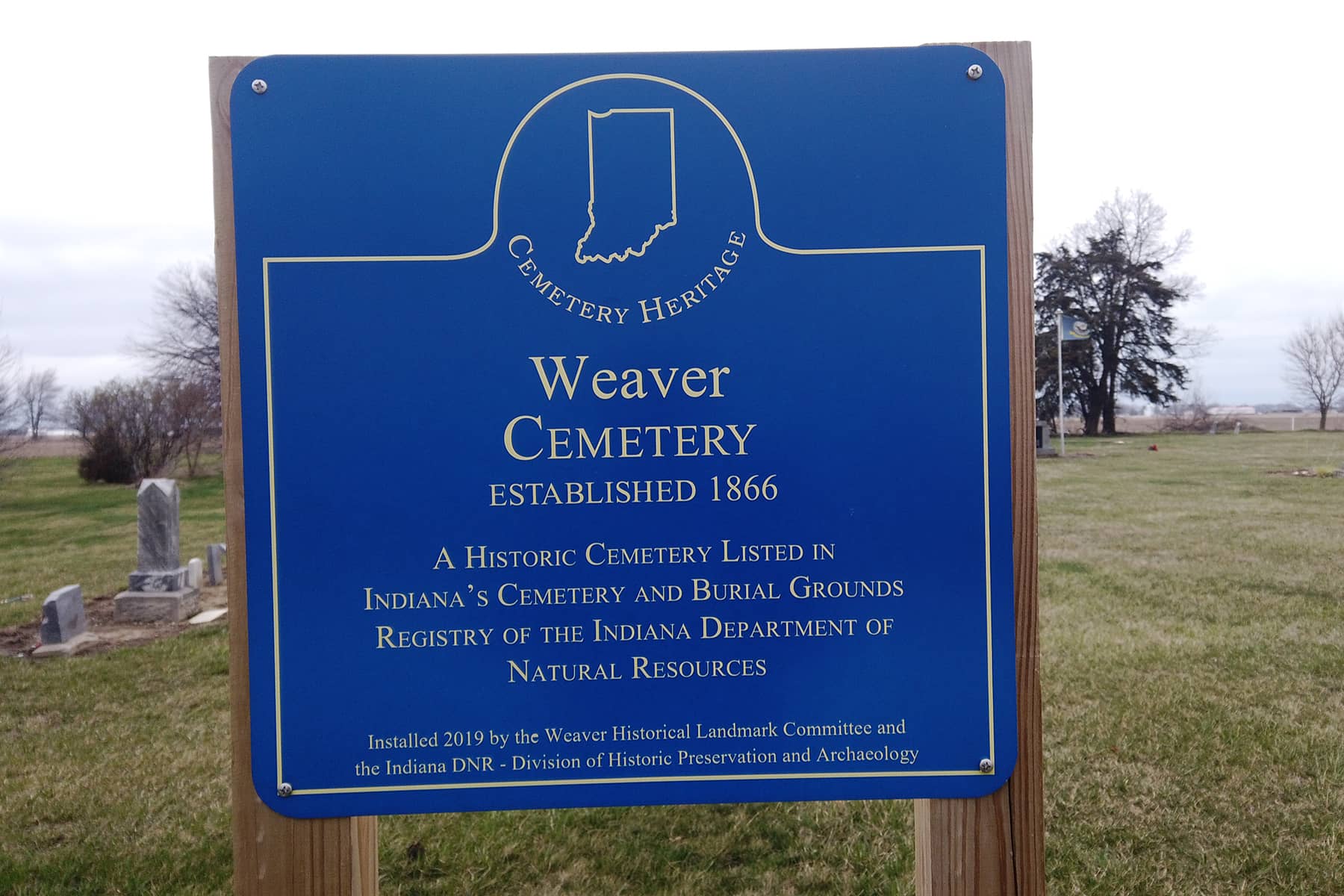

That same year, 2005, I made the second of what would become three trips to Marion, Indiana, the site of the lynching Cameron survived on August 7, 1930. I visited the jail he was removed from as well as the Weaver Cemetery where his two friends, Abram Smith and Thomas Shipp who were murdered that day, are buried in.

The all-black town of Weaver is where the Black residents of Marion fled to on the day of the lynching to protect themselves from the mob of at least 10,000 that would murder Smith and Shipp and beat Cameron before placing a noose around his neck. Through a miracle, he survived, and years later told the story in his memoir, A Time of Terror: A Survivors Story.

I drove to Marion on my way to be a part of a workshop entitled, Unmasked: The Antilynching Exhibits of 1935 and Community Remembrance in Indiana at Indiana University Bloomington (IU). I drove to Marion for the third time on my way to IU. I stopped at the jail for the third time and visited the cemetery for the second time. Ironically I last visited Marion 17 years ago the same year the U.S. Senate issued an apology for never passing a law to make lynching a federal crime. The jail has been converted to apartments called the Castle Condos, Suites & Apartments, just a block away from the County Courthouse and site of the lynching tree, which was cut down many years ago.

The workshop was conducted by a group at the university and scholars from multiple disciplines at universities around the country. The effort is being led by Alex Lichtenstein, Professor, Departments of History and American Studies, Rasul Mowatt, Professor, Departments of American Studies and Geography, and Phoebe Wolfskill, Associate Professor, Departments of American Studies and African American/African Diaspora Studies, all from the university in Bloomington.

“The exhibition revisits art from two highly publicized exhibitions held in New York in 1935 but aims to take the concerns from this exhibition to individual spaces that witnessed lynching and bring it into contemporary discussions about racial violence and teaching tolerance.”

The effort in 1935 did not lead to success. As I contemplate the effect of the latest attempt to assuage the guilt America has over thousands of lynchings I keep hearing people say the passage of this bill so many years later is “better late than never.” That sounds disrespectful to my ears.

Many have celebrated the Emmett Till Antilynching Act, signed into law on March 29, 2022. I see no reason to celebrate a law that is one hundred years late and is not an anti-lynching bill, despite the name.

The law simply makes what Congress calls “lynching” a federal hate crime. They don’t define lynching in the bill. It’s called an anti-lynching bill but the words of the the bill simply amend Section 249(a) of title 18, United States Code, which is the legislation about federal hate crimes. This is the text of the bill.

To amend section 249 of title 18, United States Code, to specify lynching as a hate crime act.

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled,

SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE.

This Act may be cited as the “Emmett Till Antilynching Act.”

SEC. 2. LYNCHING; OTHER CONSPIRACIES.

Section 249(a) of title 18, United States Code, is amended by adding at the end the following:

“(5) LYNCHING.—Whoever conspires to commit any offense under paragraph (1), (2), or (3) shall, if death or serious bodily injury (as defined in section 2246 of this title) results from the offense, be imprisoned for not more than 30 years, fined in accordance with this title, or both.

“(6) OTHER CONSPIRACIES.—Whoever conspires to commit any offense under paragraph (1), (2), or (3) shall, if death or serious bodily injury (as defined in section 2246 of this title) results from the offense, or if the offense includes kidnapping or an attempt to kidnap, aggravated sexual abuse or an attempt to commit aggravated sexual abuse, or an attempt to kill, be imprisoned for not more than 30 years, fined in accordance with this title, or both.”

The bill can be analyzed by looking at the one and only actual anti-lynching bill ever passed by Congress. Seeing that bill shows that this most recent bill is not an anti-lynching law. On January 26, 1922, the Dyer Anti-lynching Bill passed by a vote of 231 to 119 in the House of Representatives. Four members of the House of Representatives voted “present” and another 74 chose to not vote. Four future Speakers of the House voted no. After the House passed the bill it was sent to the Senate Judiciary Committee. They passed it on to the Senate floor for a vote, but a filibuster by Senate Democrats made sure it would never pass. These are the first words of the bill:

“AN ACT To assure to persons within the jurisdiction of every State the equal protection of the laws, and to punish the crime of lynching. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That the phrase “mob or riotous assemblage,” when used in this act, shall mean an assemblage composed of three or more persons acting in concert for the purpose of depriving any person of his life without authority of law as a punishment for or to prevent the commission of some actual or supposed public offense. That if any State or governmental subdivision thereof fails, neglects, or refuses to provide and maintain protection to the life of any person within its jurisdiction against a mob or riotous assemblage, such State shall by reason of such failure, neglect, or refusal be deemed to have denied to such person the equal protection of the laws of the State, and to the end that such protection as is guaranteed to the citizens of the United States by its Constitution …”

The law states that officials charged with protecting persons from a mob intent on lynching, “who fails, neglects, or refuses to make all reasonable efforts to prevent such person from being so put to death, or any State or municipal officer charged with the duty of apprehending or prosecuting any person participating in such mob or riotous assemblage who fails, neglects, or refuses to make all reasonable efforts to perform his duty in apprehending or prosecuting… shall be punished by imprisonment not exceeding five years or by a fine of not exceeding $5,000, or by both such fine and imprisonment.”

If that person in custody is killed, the officers “shall be guilty of a felony, and those who so conspire, combine, or confederate with such officer shall likewise be guilty of a felony. On conviction the parties participating therin shall be punished by imprisonment for life or not less than five years.”

These penalties are designed to be a deterrent to those allowing lynchings to take place. In 1922, 57 lynching occurred and 51 Black victims lost their lives that year. It was the last year that lynchings exceeded 50 in number. There were never more than 33 lynchings after 1923.

In 1935 another attempt was made. New York Democratic Senator Robert F. Wagner and Senator Edward Costigan had agreed to draft an anti-lynching bill the previous year. The Costigan-Wagner bill proposed federal prosecution of participants in lynch mobs including any officials or law enforcement officers, who failed to protect victims in their custody. The bill was designed to end mob rule and “vigilante justice” targeted at the Black community. President Franklin D. Roosevelt refused to support the bill because of his fear of losing White votes in the South. The bill never made it to the Senate floor. There were 20 lynchings in 1935.

The fact that the Senate waited until 2005 to apologize for never passing an anti-lynching law says a lot. Dr. Cameron attended the event where the Senate resolution was announced on June 13, 2005. This is part of the resolution:

“Apologizing to the victims of lynching and the descendants of those victims for the failure of the Senate to enact anti-lynching legislation … Whereas lynching was a widely acknowledged practice in the United States until the middle of the 20th century; Whereas lynching was a crime that occurred throughout the United States, with documented incidents in all but 4 States; Whereas at least 4,742 people, predominantly African-Americans, were reported lynched in the United States between 1882 and 1968; Whereas 99 percent of all perpetrators of lynching escaped from punishment by State or local officials; Whereas nearly 200 anti-lynching bills were introduced in Congress during the first half of the 20th century; Whereas, between 1890 and 1952, 7 Presidents petitioned Congress to end lynching; Whereas, between 1920 and 1940, the House of Representatives passed 3 strong anti-lynching measures.”

Only 78 of the 100 members of the Senate signed the resolution. Seventeen years later both houses of Congress combined to pass a law they have the audacity to call an anti-lynching. The “bill” does not provide for the protection for lynchings. The types of lynchings the bills in 1922 and 1935 sought to punish are relics of America’s past. Despite the fact that people are calling many crimes against Blacks today lynchings, shows a lack of understanding of what lynchings were. I suggest those who want to use the term lynching today take a look at the dozens of souvenir lynching postcards in the book Without Sanctuary. I suggest they read the article in 1955 in Look Magazine where the men who lynched Emmett Till confessed to the kidnapping and murder.

Symbolic measures to assuage the guilt related to racist discrimination against Blacks throughout American history are all the rage nowadays. This is simply the latest iteration of these mostly empty gestures that are supposed to show us how empathetic Americans are to the plight of Black people.

Of course some appreciate the law. Michelle Duster, is the great-granddaughter of Ida B. Wells. Wells who documented the history of lynchings in Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases (1892) and A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynchings in the United States (1895). Duster was interviewed by Democracy Now about the passage of the law.

“Since my great-grandmother’s visit to the White House 124 years ago, there have been over 200 attempts to get legislation enacted. … But we finally stand here today, generations later, to witness this historic moment of President Biden signing the Emmett Till anti-lynching bill into law … finally, in 2022, we have justice; we have laws put in place that were fought for so long ago. But, you know, better late than never. And hopefully, going forward, there will be more justice for crimes that are hate-based and racially based.”

Democracy Now also interviewed Reverend Wheeler Parker Jr., Emmett Till’s cousin, and best friend.

“I have great commendations for those who had the courage and the fire and the guts in their belly to do what’s right. Over 200 times these guys have stood up and did it. It speaks volumes, not only for them but for America. Let us know that the wheels of justice grind, but they grind slow. They got the job done. And sometimes you’re tempted to have bitterness: Why did it take so long? And it shouldn’t have taken that long. But we appreciate it, and we’re thankful for what was done and when it was done.”

I appreciate that Duster and Parker Jr. feel this is a positive moment to be celebrated. However, I’m tired of apologies and laws that come decades too late to have any real meaning. Congress has the responsibility to pass laws that protect Americans, and they have failed at this time and time again when it comes to Black people.

Making lynchings a “hate crime” is not what this bill does. It tries to convince us that it is doing that. Using Emmett Tills name on a bill 67 years after he was lynched, does not make this an anti-lynching bill.

We need to begin to understand that “empty platitudes” such as those in this law don’t undo the damage or mitigate the pain and misery caused by lynchings and other anti-black terrorism. The victims of lynchings were not the only people who suffered. The families are still suffering all these years later. Most of them are too traumatized to even discuss the lynching of their loved ones. The passage of time has not made it better. The passage of this bill will not make it better.

The people who perpetrated these horrific public lynchings were rarely ever punished. They lived the rest of their lives enjoying the memory of the lynching, possessing souvenirs such as pictures of the lynching, pieces of the lynching rope, body parts cut off of the victims, and bark from the lynching trees were among many of the “keepsakes” lynchers and their supporters valued so much.

This bill, 17 years after the Senate “apology” in 2005, is a sign of the failures of that body to do the right thing in a timely manner. No apology or fake anti-lynching bill will make up for the inaction by multiple Congress’s and multiple Presidents to protect Black people from White mob violence.

Dr. Cameron told me how disappointed he was that so few members of Congress were in the chambers on June 13, 2005 when the resolution was issued. He called it a good attempt, but far from what was needed. On that day 20 of the 100 senators had not signed a statement of support of the apology resolution.

“The apology is a good idea, but it still won’t bring anyone back. I hope that the next time it won’t take so long to admit to our mistakes.”

© Photo

Reggie Jackson