One of the shifts taking place in equity work and conversations is a shift away from strictly talking about racism to include much more inclusive types of marginalization and discrimination.

I find that there are two main reasons for this shift. The first of these makes perfect sense. There are more forms of discrimination than just anti-Black racism in American society. Those other marginalized and horribly treated communities are making their voices heard and are openly telling their stories. I am glad we are addressing all of those other things in a way that we never have before.

Secondarily the shift is occurring because far too many people are afraid of the elephant in America’s living room, anti-Black racism. It is the most entrenched, debilitating, engrained in the psyche, form of oppression in the history of this country.

This is not an attempt to compare who has experienced the most trauma, or what community gets marginalized the most. It is simply a fact of American life. No other marginalized group was enslaved in the millions for 246 years. No other form of hate led men to fight to keep their foot on the neck of one group of people, to the extent that they were willing to kill fellow citizens in the bloodiest war of the nation’s history.

No other group in America had a scientific racism develop to justify their mistreatment in the way that Black people did. No other group was freed from enslavement and then murdered by the tens of thousands while being told they were free. No other group had racial codes written to criminalize their behavior. No marginalized community had to fight as long and as hard, time and time again, be treated as human beings.

Anti-Black racism is not the same as anti-semitism in America. Sexism is not the same as anti-Muslim discrimination in America. Anti-Asian hatred and violence is not the same as anti-LGBTQ hatred and discrimination. Yet, many would have you believe we need to learn about each of these in the same way. We don’t.

They are all very different things and deserve to be studied and fought against based on how they manifest themselves in this country. One size does not fit all when it comes to this work. A model that uses that approach will be ineffective and push each group to the margins of the workspace. Each marginalized group deserves specific attention to their unique challenges.

The fight against anti-Black racism was the foundation of the fight for Civil Rights in the 1950s and 1960s. The fight against anti-Black violence and hatred is what got us to where we are today. The racial reckoning came about due to the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery. The massive protests that began in Minneapolis after Floyd was murdered, and eventually spread around the world, was a reaction to anti-Black racism.

As we now grapple with that racial reckoning, people want to play the “it’s all the same’ game. It is not. We will not be successful if we fail to understand this very basic point. That does not mean we should ignore any of the other forms of bias and bigotry. They are all important. However, until American culture figures out how to acknowledge the abhorrent treatment of Black people and fight like heck to end that system, none of those other issues will be resolved either.

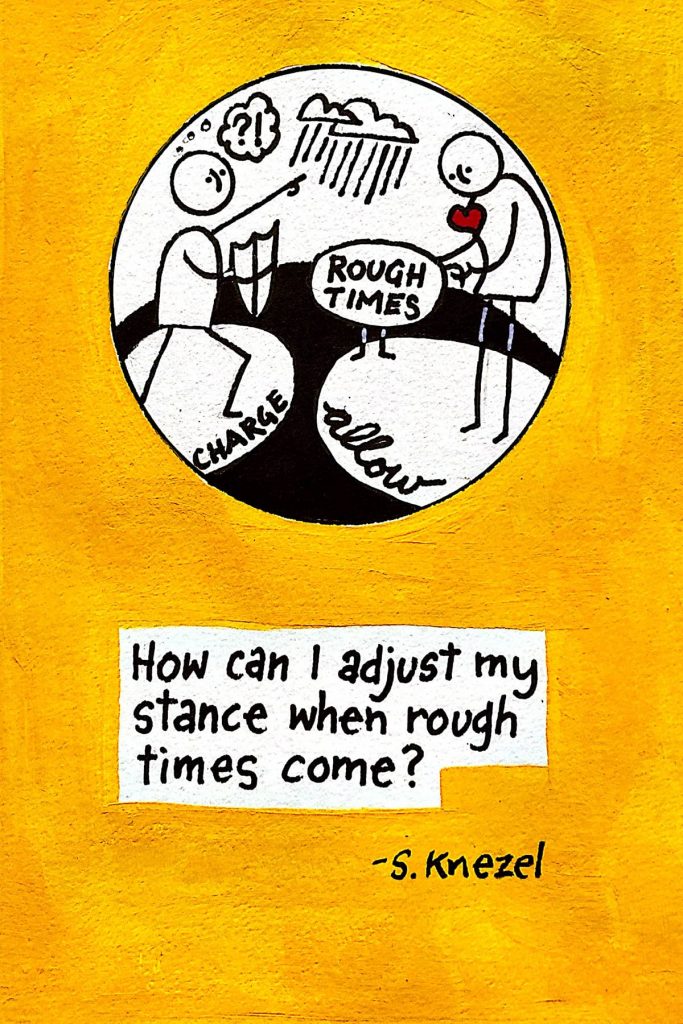

If you go to the hospital and say you have been bitten by a poisonous snake, they will ask right away what kind of snake it was. I doubt that the anti-venom for a rattlesnake is the same as that for a copperhead, or a cottonmouth. We cannot treat all of the forms of discrimination the same anymore than a doctor would treat every snake bite the same.

Specificity of understanding is required to fight intelligently. All of the “-isms” have some things in common, but they all play out in a different way in the daily lives of people in this country. Anti-Black racism can come from people in some of the other marginalized groups, and often does. Black people can be bigoted and homophobic, while at the same time they are the victims of racism.

This might come as a surprise to some who want to do the right thing. There is still a fear of acknowledging anti-Black racism because many of the people who are actively engaged in anti-racist work feel a level of guilt. They know that they come from a community that has helped to create and maintain anti-Black racism. They know clearly that many of people in their social circles could care less about ending anti-Black racism. They have friends and family members who are actively racist.

I have tried very hard to learn from mistakes I have made. I try really hard to mostly stay in my lane, and stick with what I know. That means that I stay in this work but focus most of my efforts on educating about anti-Black racism. That is not only what I know, but it is clearly what I have experienced.

I know things about other marginalized groups because I have taken the time to learn those stories very intentionally. That is an ongoing journey for me. I do not want to pretend to be an expert on those other types of being marginalized and facing discrimination. There are lots of people who are experts and could more effectively provide the type of advice and training needed for those issues. I know some of these people in the local and national community. We need them to do this work, and it can only start when we reach out to these people.

I will always advocate in the same way by shouting from any platform I have available, that the most important issue related to discrimination in this country, is anti-Black racism. People might disagree with that statement and that is okay. However, I believe when others study American history in the way that I do, it will become crystal clear.

We should fight like the U.S. military does. We have different branches of the military to handle very specific types of engagements. We would never ask our Army personnel to leave their land bases and take command of our naval fleet. It would be crazy to expect that tank drivers could navigate aircraft carriers. They have integrated missions, but different skills and very specific tools at their disposal.

In the work of social and racial justice, there needs to be the same level of thought that goes into the work. Otherwise, the efforts will get sanitized and marginalized in such a way. That will ultimately not be effective in any of the spaces it is needed in.

© Photo

Dаvіd Clоdе