Across the Fukushima, Miyagi, and Iwate Prefectures on the east coast of Honshu Island north of Tokyo, lessons of the past resonate through cities marked by both absence and revival. The Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011, which was followed by a catastrophic tsunami and nuclear disaster, redefined the essence of community, memory, and the unyielding spirit to rebuild.

Memorials to the past often take on a life of their own because of a single tragic and often random event that forever connects them by geographic location, like the Genbaku Dome in Hiroshima – the iconic building that survived an atomic blast that vaporized the entire city.

For the Tōhoku region, consisting of the six prefectures Akita, Aomori, Fukushima, Iwate, Miyagi, and Yamagata, memorial relics from March 11 remain as an interwoven narrative of loss, memory, and resurgence.

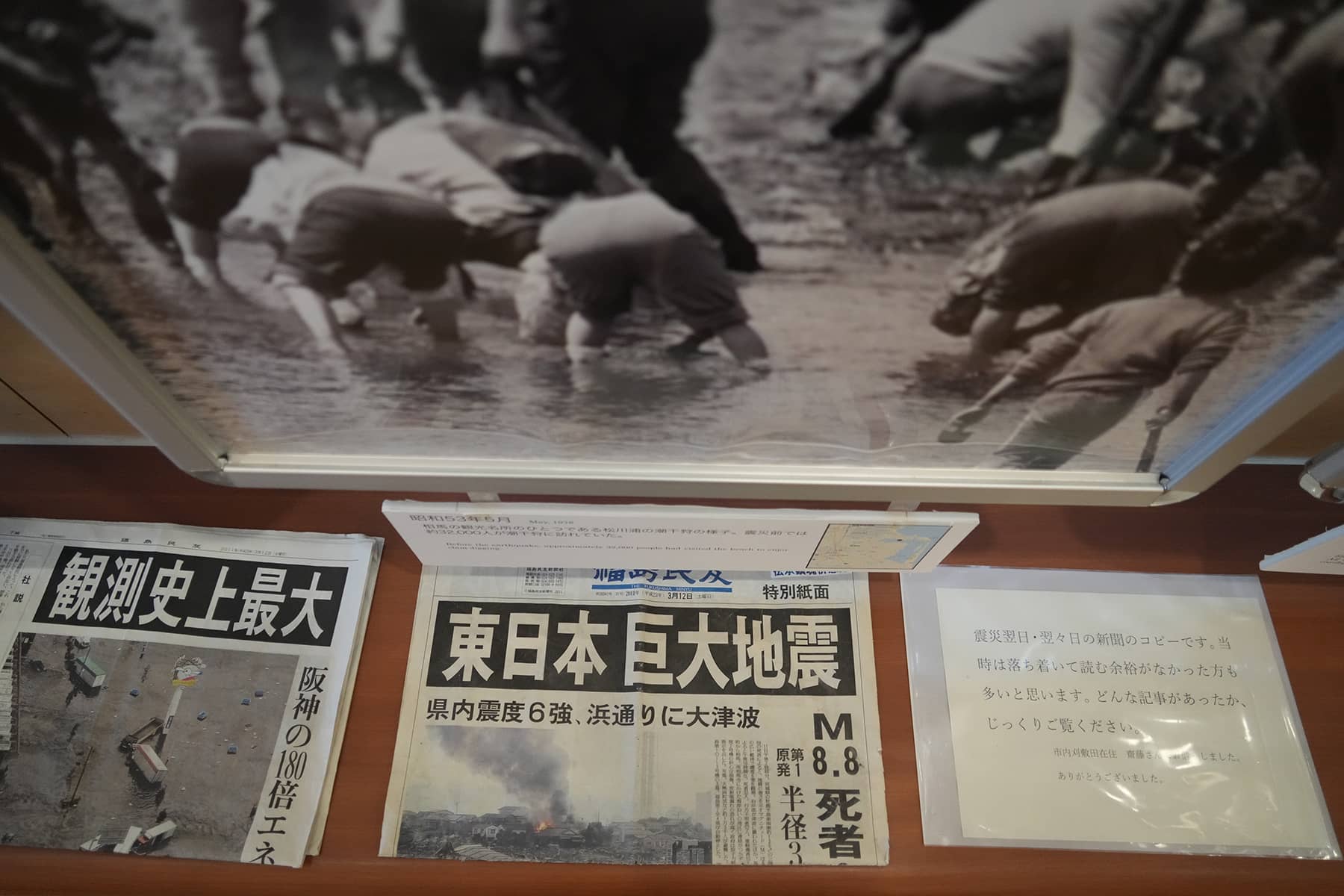

Known as the 3.11 Densho Road, the network of disaster memorial facilities conducts an assortment of projects related to disaster prevention and preservation. The initiatives educate the public about the lessons from the Great East Japan Earthquake.

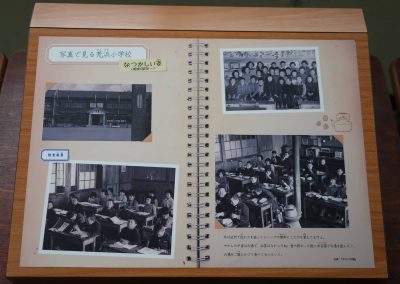

On the very grounds where tsunami waves washed away the future for so many youths, the Kesennuma City Memorial Museum stands as one such reminder. The facility is located at the former Kesennuma Koyo High School, which has been preserved in its original condition at the time of the disaster.

“Our goal is to preserve the memories and lessons of the disaster for the future, and serve as ‘visible evidence’ about what happened on March 11, 2011,” said the memorial museum’s director Ichiro Haga. “We want visitors to feel the importance of disaster prevention awareness and evacuation.”

In Kesennuma, 1,143 people were killed by tsunami and fire and 212 are still missing. Storage tanks for marine fuel collapsed at the fishing port and spread to the surrounding residential areas. When it was ignited, the massive fire destroyed homes not washed away by the tsunami.

Haga was a part-time teacher at the Kesennuma Koyo High School, having retired from full-time teaching at the school after a 17-year career. He still has a vivid recollection of the day of the earthquake.

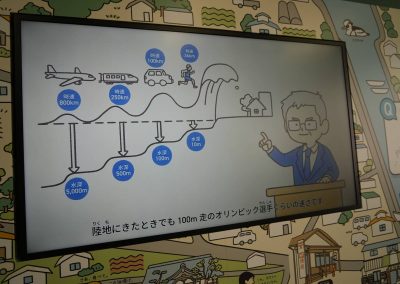

“I had taught classes in the morning, and the terrifying tsunami struck shortly after I got home. Roughly 250 people, including students, teachers, and construction workers, were at the Kesennuma Koyo High School that day,” said Haga. “The school building, which was located only about 480 feet away from the coast, at a height of just three feet above sea level, was hit by a massive tsunami wave with a height of more than 42 feet. We had no casualties, however, thanks to the quick evacuation and appropriate actions taken, which I think is nothing short of a miracle.”

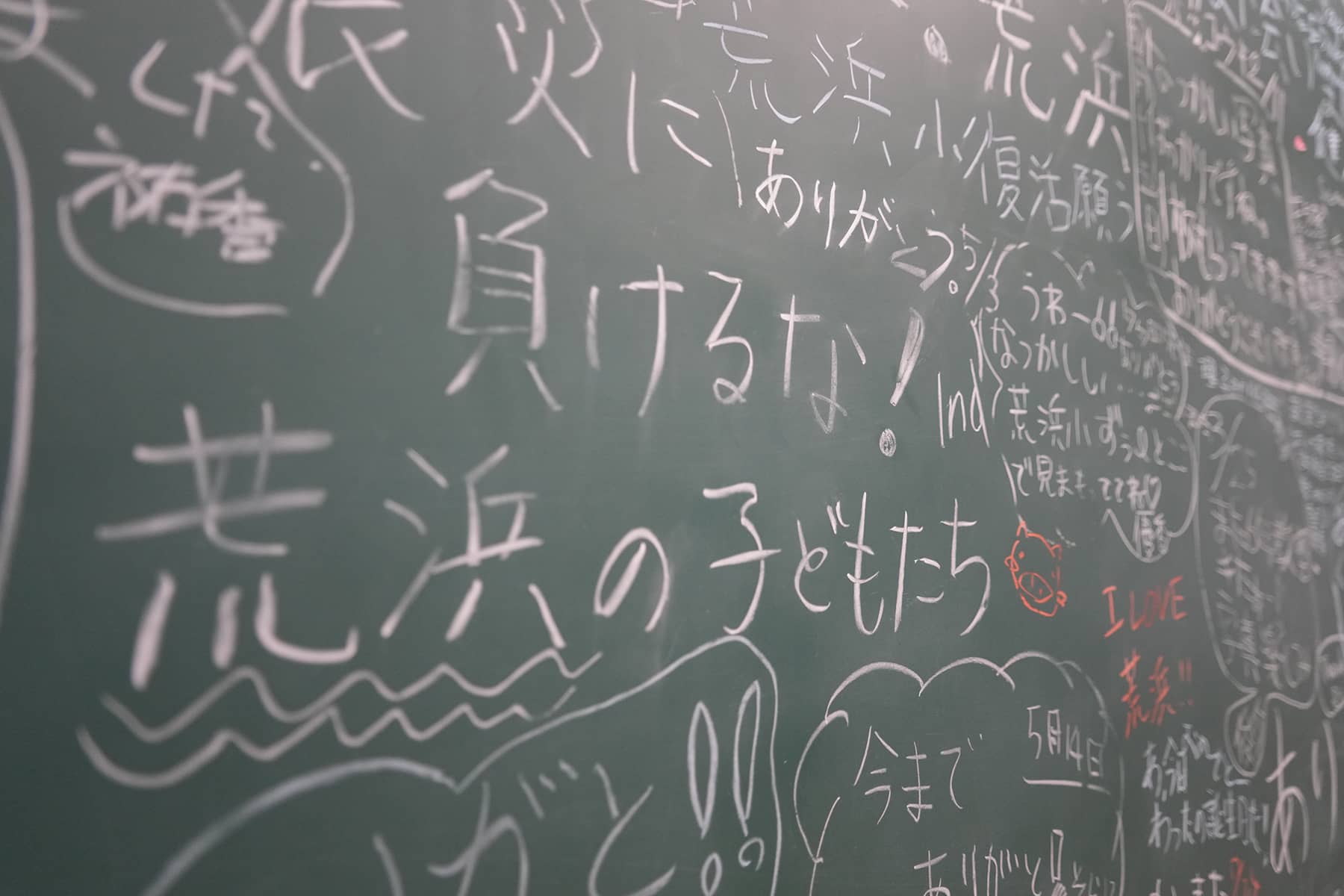

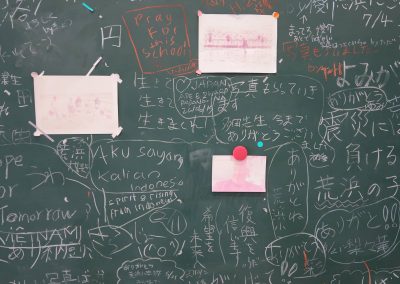

Former director Katsumi Sato set a strict policy for the museum, whereby staff would not enter or touch the fenced-in area of the earthquake ruins. Most of the glass in classrooms and hallways was broken, so when it rains many interior spaces get wet, in winter snow often piles up, ocean breezes in the summer can stir dust and nudge objects, and weeds grow in the gymnasium where the roof was washed away.

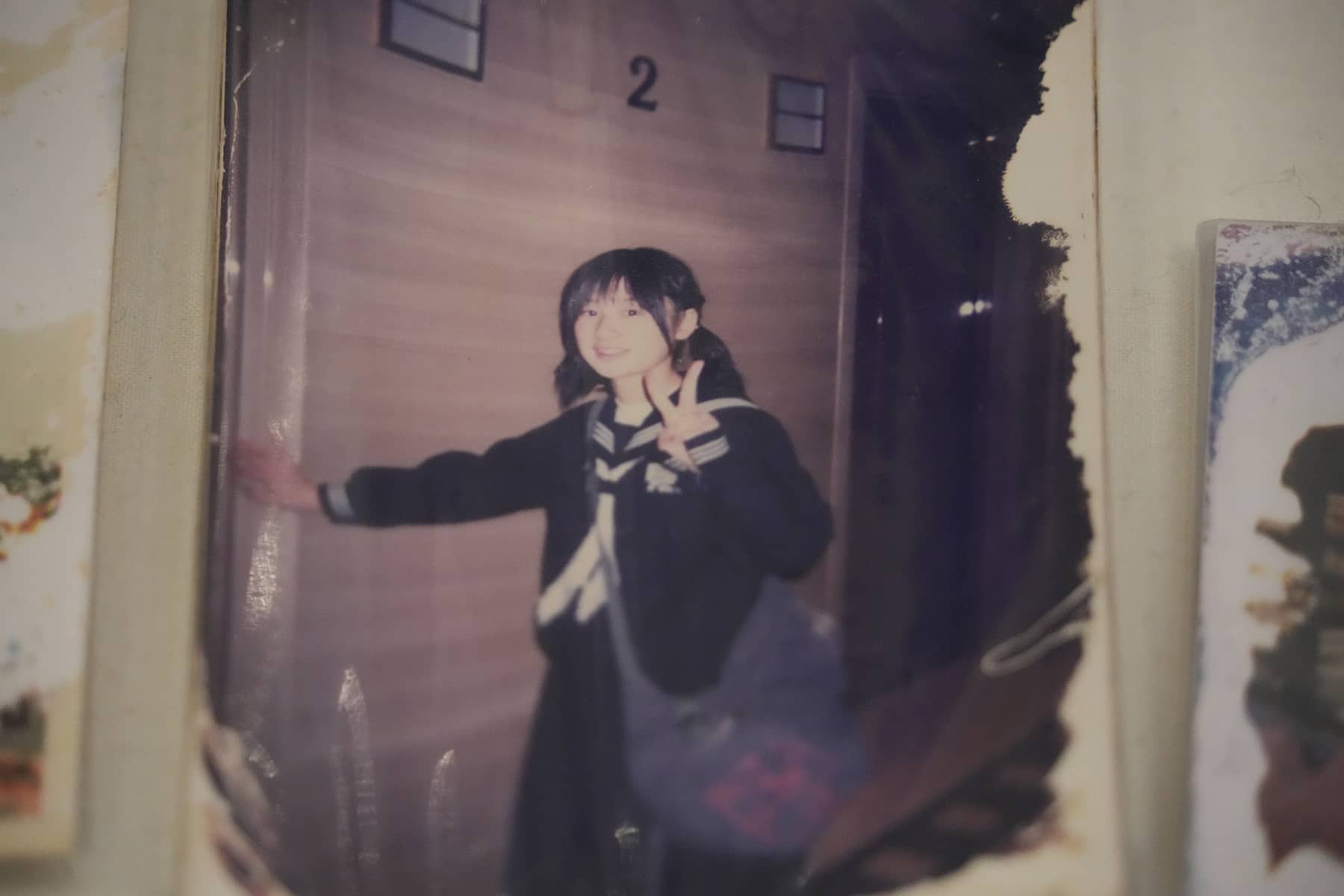

The museum is one of many former schools to meticulously preserve the remnants of the disaster, including classrooms where desks and chairs are still scattered in disarray from that day in 2011.

Among such relics is a full-sized motor vehicle that was washed into the third floor of the building, remaining as a visual echo of the tsunami’s chaos. Through exhibits like that, visitors are confronted with the raw power of the natural world, a necessary step in fostering a culture of preparedness and resilience.

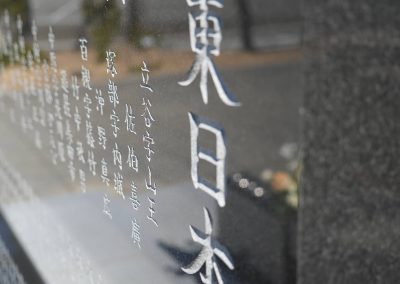

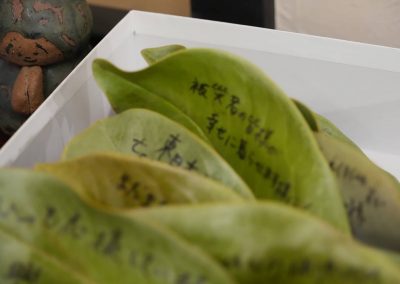

On Mt. Anba, memories also take shape in the form of art. Kesennuma Reconstruction Memorial Park opened in 2021, a decade after the earthquake. It features a 30-foot-high monument, called the “Prayer’s Sail,” which resembles a ship’s sail.

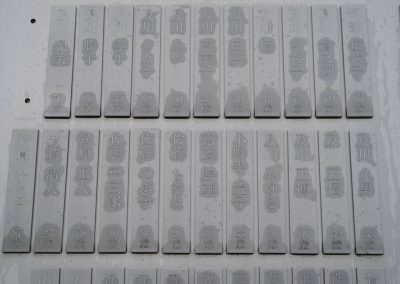

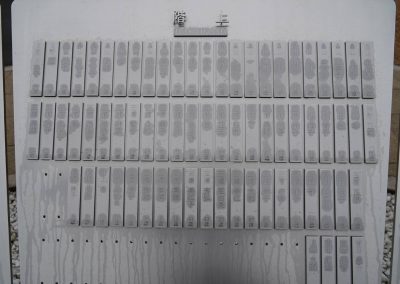

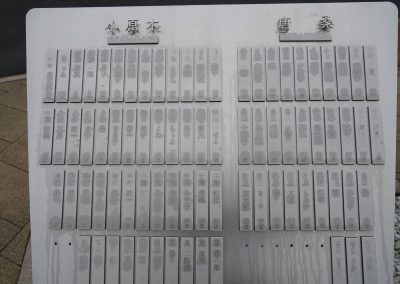

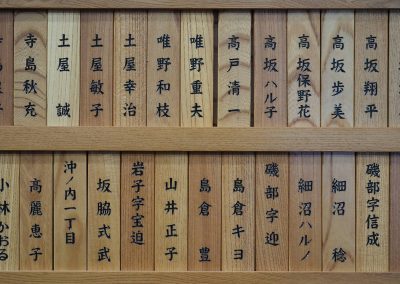

The symbol of healing and recovery offers a place to pray in the direction of the sea from where the tsunami came. Surrounding the prayer space are the nameplates listing the deceased. Interspaced around the site are five sculptures by Yoshihiro Minagawa, created to recall and pass on memories from that tragic day.

TO THE SEA: “Today is the anniversary of your death. My life has changed since that day. But I still love this place.”

SORRY: “I was holding your hand that day. But I let it go. I’m sorry I’m the only one left alive.”

THANK GOD: “You’re alive! I’m really glad. I thought you weren’t alive because everything was washed away.”

FETCHING WATER: “The parents have not yet returned. Grandmothers are shivering with cold. Small children are crying. We are going to fetch water.”

MARCH: “Unhealed grief, love for my family, and unfulfilled dreams. Every year in March, my feelings deepen.”

Among Kesennuma’s architectures of survival one structure in particular stands as a beacon of ingenuity and foresight. Revered as the “The Spiral Staircase of Life,” it was erected by Taiji Abe and is credited as saving more than two dozen lives.

The local business owner had personally witnessed the devastation of the 1960 Valdivia earthquake and tsunami in Chile. As a result of that traumatic experience, Abe installed a spiral staircase outside his three-story steel-frame home in 2006.

Abe founded the Abecho Shoten company, which operates fisheries and tourism businesses in Kesennuma, Minami Sanriku, Ishinomaki, and Ofunato. Aware of the tsunami danger in the area, the staircase was added for the purpose of evacuating local residents in an emergency. During the 2011 tsunami it became a sanctuary for about 30 residents.

“What you learn in hard times may widely change your life.” – Taiji Abe

Shortly after Abe’s death in 2019, his former family home and private disaster relic was relocated to its preservation location about 280 feet away using a towing method to avoid dismantling the building.

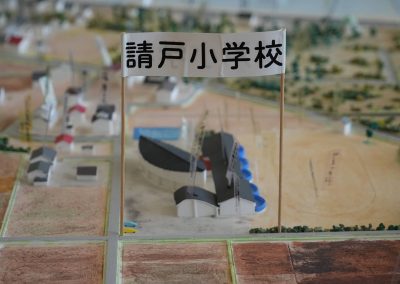

In other places across Tōhoku, memorials stand not just as silent witnesses to the tragedy but as connectors to the past and lives lost. Such sites include the former Nakahama Elementary School, and the Kadonowaki Elementary School in Ishinomaki. Both sites serve the dual purposes of honoring those who perished, and educating visitors about the destructive power of nature and the importance of emergency preparedness.

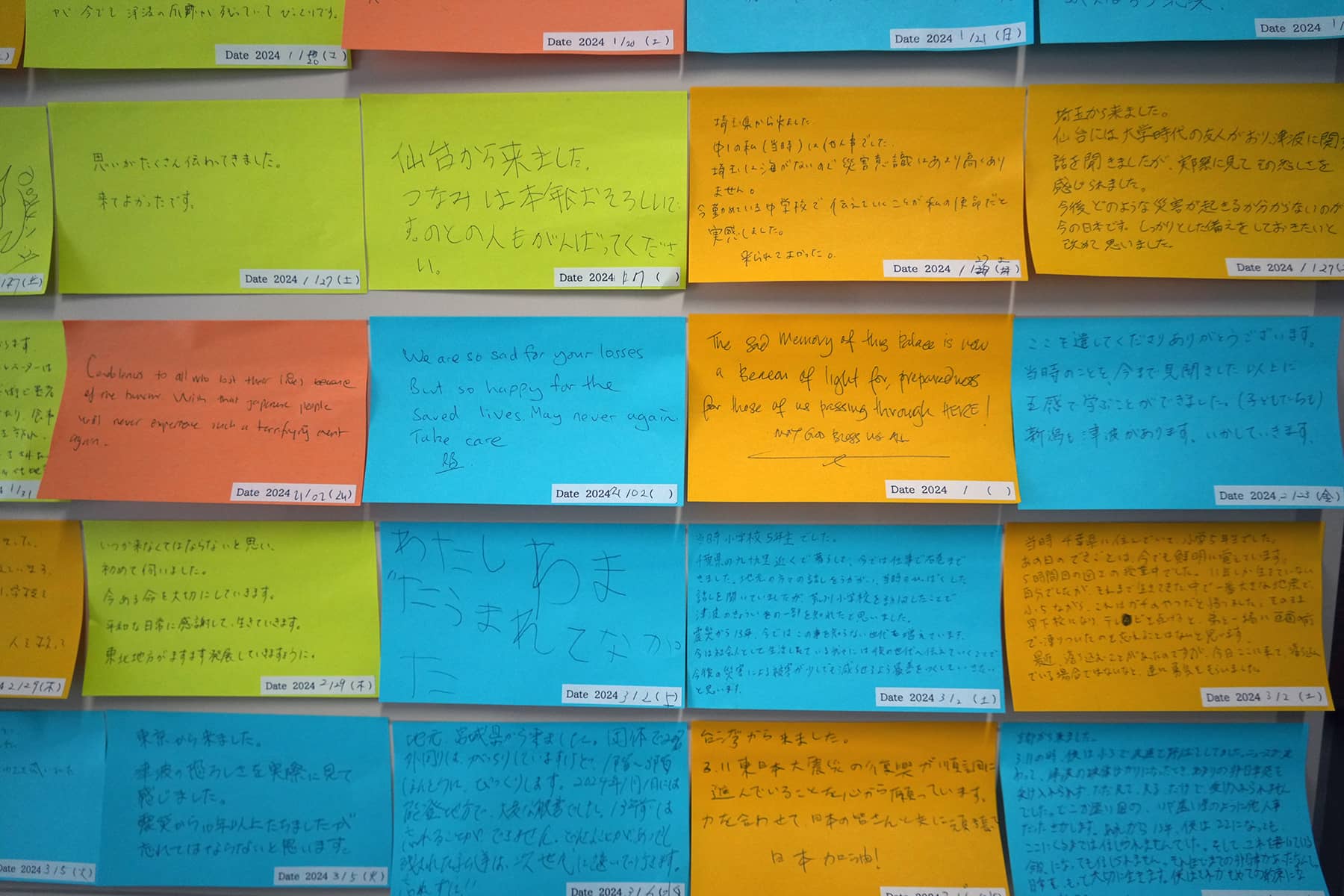

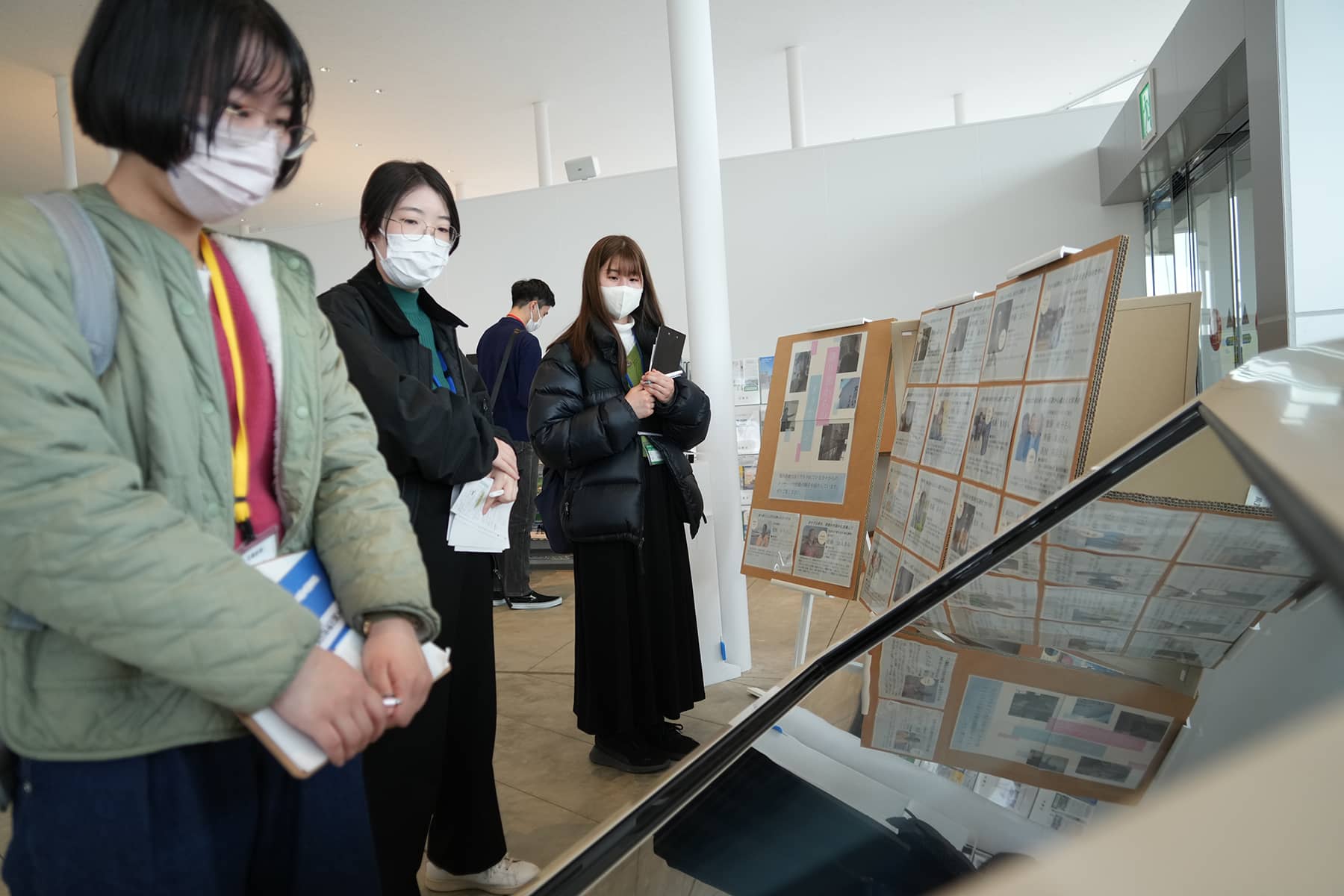

Efforts across Fukushima, Miyagi, and Iwate Prefectures aim to attract school groups and visitors to disaster-affected areas, not only to keep the memory of the tragedy alive but also to promote regional tourism. The educational tours, promoted under 3.11 Densho Road and endorsed by the Memorial Network, draw a direct line from past losses to future readiness.

The work ensures that the lessons from the 2011 tragedy will not be forgotten, fostering a culture of respect for nature’s might. In the face of the next disaster, such memorials teach that resilience, memory, and education are the most powerful tools for survival.

3.11 Exploring Fukushima

- Journey to Japan: A photojournalist’s diary from the ruins of Tōhoku 13 years later

- Timeline of Tragedy: A look back at the long struggle since Fukushima's 2011 triple disaster

- New Year's Aftershock: Memories of Fukushima fuels concern for recovery in Noto Peninsula

- Lessons for future generations: Memorial Museum in Futaba marks 13 years since 3.11 Disaster

- In Silence and Solidarity: Japan Remembers the thousands lost to earthquake and tsunami in 2011

- Fukushima's Legacy: Condition of melted nuclear reactors still unclear 13 years after disaster

- Seafood Safety: Profits surge as Japanese consumers rally behind Fukushima's fishing industry

- Radioactive Waste: IAEA confirms water discharge from ruined nuclear plant meets safety standards

- Technical Hurdles for TEPCO: Critics question 2051 deadline for decommissioning Fukushima

- In the shadow of silence: Exploring Fukushima's abandoned lands that remain frozen in time

- Spiral Staircase of Life: Tōhoku museums preserve echoes of March 11 for future generations

- Retracing Our Steps: A review of the project that documented nuclear refugees returning home

- Noriko Abe: Continuing a family legacy of hospitality to guide Minamisanriku's recovery

- Voices of Kataribe: Storytellers share personal accounts of earthquake and tsunami in Tōhoku

- Moai of Minamisanriku: How a bond with Chile forged a learning hub for disaster preparedness

- Focus on the Future: Futaba Project aims to rebuild dreams and repopulate its community

- Junko Yagi: Pioneering a grassroots revival of local businesses in rural Onagawa

- Diving into darkness: The story of Yasuo Takamatsu's search for his missing wife

- Solace and Sake: Chūson-ji Temple and Sekinoichi Shuzo share centuries of tradition in Iwate

- Heartbeat of Miyagi: Community center offers space to engage with Sendai's unyielding spirit

- Unseen Scars: Survivors in Tōhoku reflect on more than a decade of trauma, recovery, and hope

- Running into history: The day Milwaukee Independent stumbled upon a marathon in Tokyo

- Roman Kashpur: Ukrainian war hero conquers Tokyo Marathon 2024 with prosthetic leg

- From Rails to Roads: BRT offers flexible transit solutions for disaster-struck communities

- From Snow to Sakura: Japan’s cherry blossom season feels economic impact of climate change

- Potholes on the Manga Road: Ishinomaki and Kamakura navigate the challenges of anime tourism

- The Ako Incident: Honoring the 47 Ronin’s legendary samurai loyalty at Sengakuji Temple

- "Shōgun" Reimagined: Ambitious TV series updates epic historical drama about feudal Japan

- Enchanting Hollywood: Japanese cinema celebrates Oscar wins by Hayao Miyazaki and Godzilla

- Toxic Tourists: Geisha District in Kyoto cracks down on over-zealous visitors with new rules

- Medieval Healing: "The Tale of Genji" offers insight into mysteries of Japanese medicine

- Aesthetic of Wabi-Sabi: Finding beauty and harmony in the unfinished and imperfect

- Riken Yamamoto: Japanese architect wins Pritzker Prize for community-centric designs

MI Staff (Japan)

Lее Mаtz