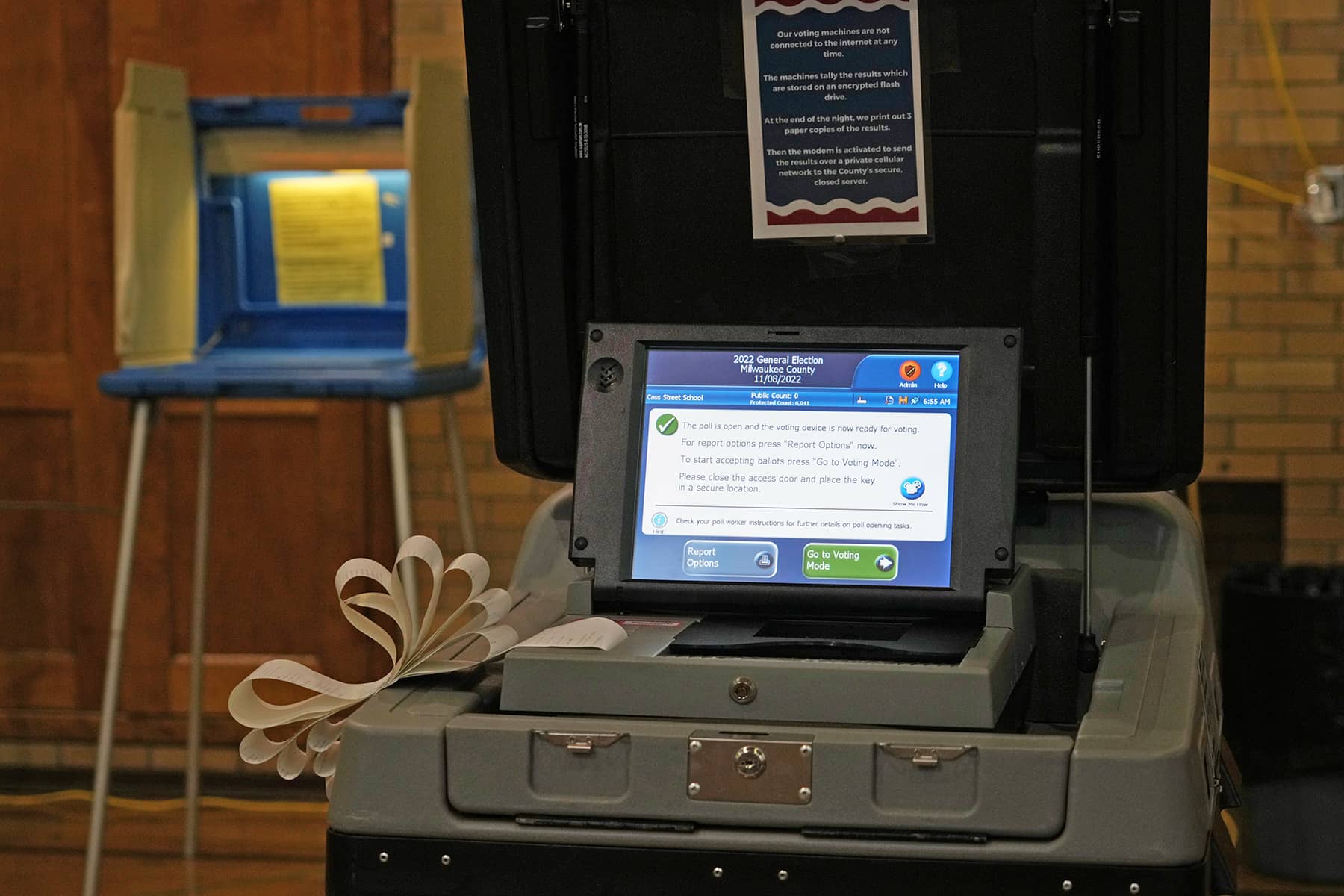

Wisconsin election officials are weighing whether changes to military absentee voting are needed after a top Milwaukee election official was charged with fraud in false requests for military absentee ballots just days before the November 8 election.

Kimberly Zapata, former deputy director of the Milwaukee Election Commission, is accused of taking advantage of relaxed requirements intended to help service members vote. A criminal complaint says Zapata used fictitious voter information to send three military absentee ballots to the home of a state lawmaker in October. Investigators said Zapata told them she was trying to expose vulnerabilities in the election system.

Wisconsin’s election practices have been effective at preventing widespread fraud, but Zapata’s actions damaged the public trust, said Meagan Wolfe, the nonpartisan administrator of the Wisconsin Election Commission.

The episode has prompted officials to consider how they could change the military ballot process to protect against small-scale fraud, and whether such adjustments would even be worth the effort.

Military absentee ballots are a tiny part of the vote in Wisconsin — on average about 0.07% of the absentee ballots requested, according to the election commission. That has translated to around 2,800 ballots in recent midterm elections.

“It just is really not possible to engage in much fraudulent activity without being noticed very quickly,” said Barry Burden, a political science professor and director of the Elections Research Center at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

One change members of the Wisconsin Election Commission said they are eyeing would add a layer of security by requiring military voters to verify their identity with a common access card, the standard ID issued to all service members by the Department of Defense. It is a matter the Legislature would have to take up if it were to go anywhere.

Military voters do not have to register to vote in Wisconsin and must only provide their name, address and date of birth to get an absentee ballot. Federal law prohibits states from requiring permanent overseas and military voters to provide a photo ID.

However, there could be ways to use common access cards to verify a service member’s identity without running up against the restrictions in federal law, Wolfe said.

Common access cards include a microchip that stores a service member’s personal identifying information and an authentication certificate that verifies their identity when accessing government computer systems. The same information could be used as an electronic signature for military absentee ballots.

“It’s not necessarily a photo ID requirement from what I understand how that would look,” said Wolfe. “It’s more or less an opportunity for military voters to be able to verify their identity using the technologies that they may have.”

A law enacted in Michigan earlier this year could provide a model for Wisconsin. The Michigan Legislature established electronic voting as an option for military voters, tying the unique information on their common access card to a digital ballot and thus securing the return process with the same verification used by military networks. Similar bills were introduced by Democrats in Virginia and New York.

It is not clear that requiring a common access card to request a military ballot, the most direct option to address concerns over Zapata’s actions, would also comply with federal requirements.

“It’s very possible that federal law would not allow such a framework since it would be adding an additional requirement to the voting process,” said Riley Vetterkind, a spokesman for the election commission.

While establishing electronic voting would not altogether remove the possibility for fraudulent requests, it would allow clerks to instantly verify digital ballots.

Military advocates say electronic voting is a great option to expand accessibility.

“Allowing us to vote electronically would help us more easily participate in the very democracy we serve to protect,” said Sarah Streyder, executive director of the Secure Families Initiative, a nonpartisan group advocating for military voters and their families.

Any change in Wisconsin law would need to pass the Republican-controlled state Legislature and receive the approval of Democratic Gov. Tony Evers, who vetoed more than a dozen election-related bills from Republicans in his last term.

Some lawmakers favor exploring the idea. Republican Senator Duey Stroebel said a military ID requirement “would probably go a long way towards rectifying the problem that was highlighted with the Kimberly Zapata case in Milwaukee.”

But Senate Majority Leader Devin LeMahieu said recently he has no plans to address military absentee voting in the upcoming legislative session. The election commission can still vote to recommend legislative action, though.

“It would solve two problems: one, it would prevent the abuse – potential abuse – and it would make it easier for military voters, especially those overseas where mail can be an issue,” said Don Millis, the Republican chair of the election commission.

Democratic Commissioner Ann Jacobs said military ID legislation could be a good idea if executed in a way that does not create additional barriers for service members to vote.