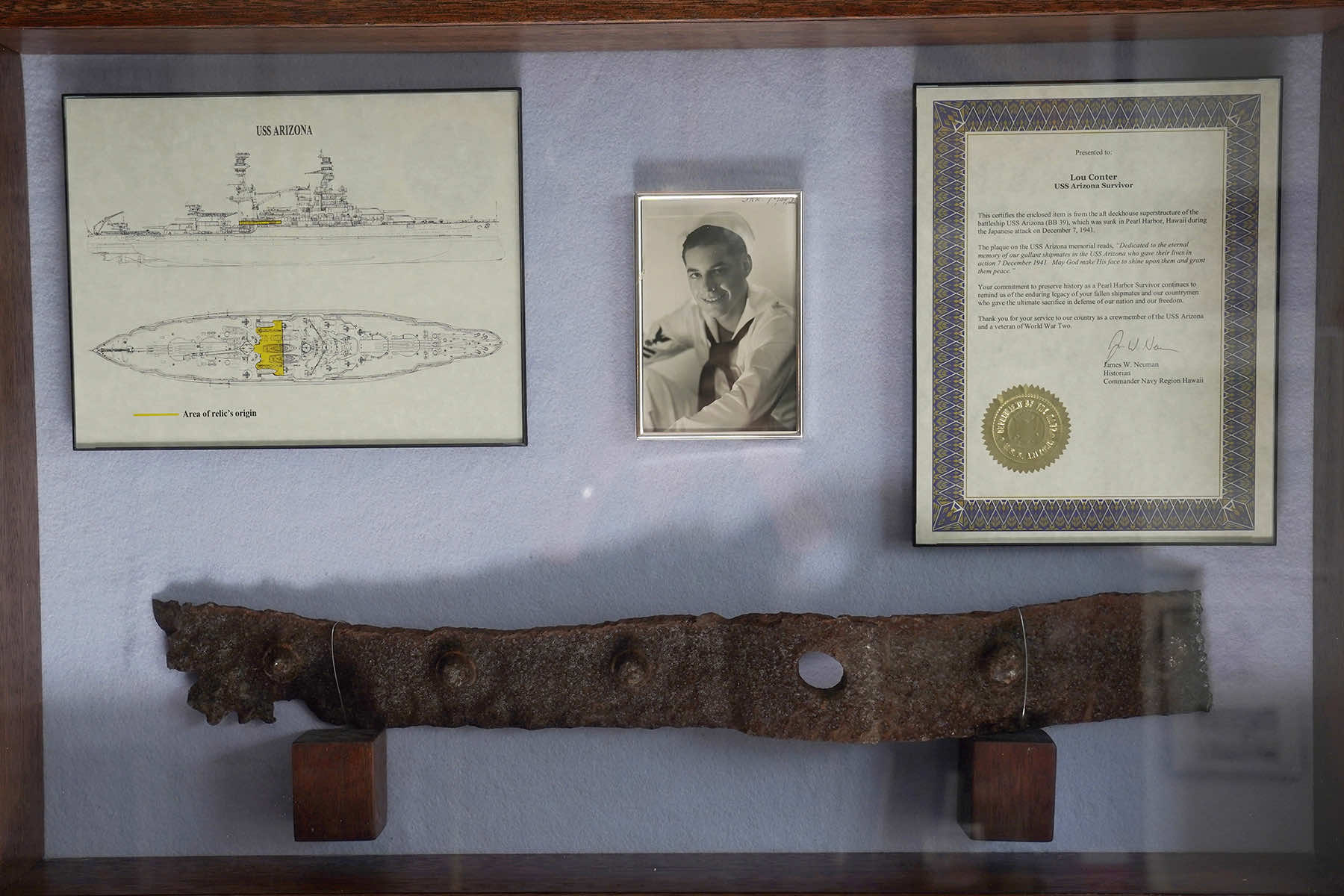

USS Arizona sailor Lou Conter lived through the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor even though his battleship exploded and sank after being pierced by aerial bombs.

That makes the now 101-year-old somewhat of a celebrity, especially on the anniversary of the December 7, 1941 assault. Many call him and others in the nation’s dwindling pool of Pearl Harbor survivors heroes. Conter rejects the characterization.

“The 2,403 men that died are the heroes. And we’ve got to honor them ahead of everybody else. And I’ve said that every time, and I think it should be stressed,” Conter said in a recent interview at his Grass Valley, California, home north of Sacramento.

On December 7, the U.S. Navy and the National Park Service will host a remembrance ceremony at Pearl Harbor in honor of those killed.

Last year about 30 survivors and some 100 other veterans of the war made the pilgrimage to the annual event. But the U.S. Navy and the National Park Service anticipate only one or two survivors will likely attend in person this year. Another 20 to 30 veterans of World War II are also expected to be there.

Conter will not be among them. He attended for many years, most recently in 2019. But his doctor has told him the five-hour flight, plus hours of waiting at airports, is too strenuous for him now.

“I’m going on 102 now. It’s kind of hard to mess around,” Conter said.

Instead he plans to watch a video feed of this year’s 81st anniversary observance from home. He is also recorded a message that will be played for those attending.

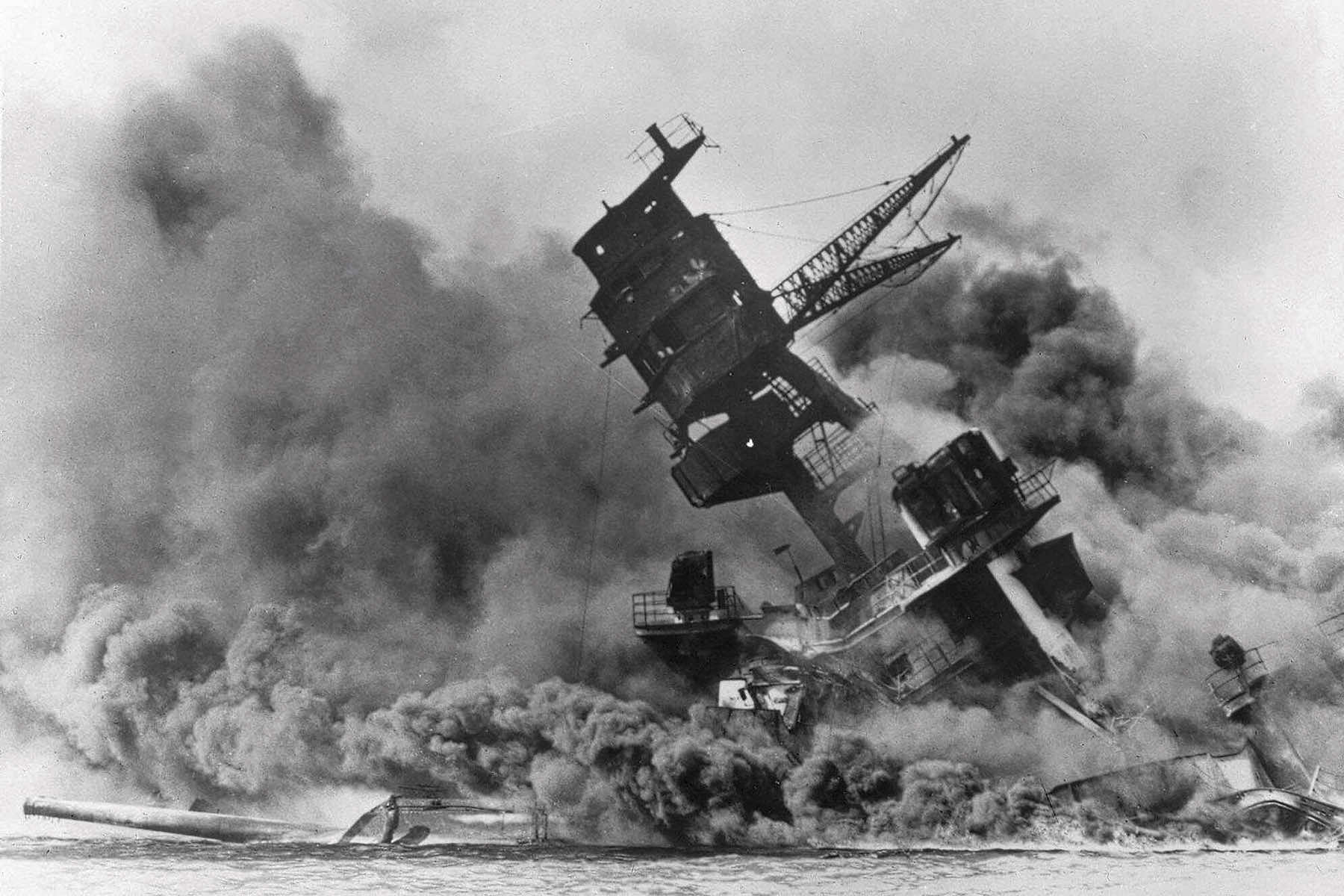

Conter’s autobiography “The Lou Conter Story” recounts how one of the Japanese bombs penetrated five steel decks on the Arizona and ignited over 1 million pounds of gunpowder and thousands of pounds of ammunition.

“The ship was consumed in a giant fireball that looked as if it engulfed everything from the mainmast forward,” he wrote.

He joined other survivors in tending to the injured, many of whom were blinded and badly burned. The sailors only abandoned ship when their senior surviving officer was sure they had rescued all those still alive.

The Arizona’s 1,177 dead account for nearly half the servicemen killed in the bombing. The battleship today sits where it sank 81 years ago, with more than 900 of its dead still entombed inside.

Conter was not injured at Pearl Harbor, during World War II or the Korean War.

This year’s remembrance ceremony is the first to be open to the public since the 2019. The pandemic forced the adoption of strict public health measures for the last two years.

David Kilton, the National Park Service’s chief of interpretation for Pearl Harbor, said he is not sure how many people will attend but they are anticipating between 2,000 to 3,000 people.

It will be held at the Pearl Harbor National Memorial visitors center which overlooks the water and the white structure built to honor those killed on the Arizona.

Organizers have set a theme of “Everlasting Legacy” for this year’s ceremony, highlighting how fewer and fewer survivors remain.

“We honestly have to know and be prepared that eventually we won’t have the ability to connect with their stories and have them with us anymore,” Kilton said. “And it’s hard to to come to grips with that reality.”

Conter went to flight school after Pearl Harbor, earning his wings to fly PBY patrol bombers, which the Navy used to look for submarines and bomb enemy targets. He flew 200 combat missions in the Pacific with a “Black Cats” squadron, which conducted dive bombing at night in planes painted black.

One night in 1943 he and his crew had to avoid a dozen or so nearby sharks after they were shot down near New Guinea.

When one sailor expressed doubt they would survive, Conter responded “baloney.”

“Don’t ever panic in any situation. Survive is the first thing you tell them. Don’t panic or you’re dead,” he said. They were quiet and treaded water until another plane came and dropped them a lifeboat hours later.

In the late 1950s, he was made the Navy’s first SERE officer — which is an acronym for survival, evasion, resistance and escape. He spent the next decade training Navy pilots and crew on how to survive if they are shot down in the jungle and captured as a prisoner of war. Some of his pupils used his instruction to live through years as POWs in Vietnam.

These days, he spends his time going to his favorite breakfast spot twice a week and going out for Mexican food every Friday night. He enjoys visiting with friends and watching TV.

Conter has not forgotten his shipmates. He said he would like the military to try to identify 85 Arizona sailors who were buried as unknowns in a Honolulu cemetery after the war.

“They should never give up on that issue. If they’re ever identified, I’m sure their families would want to bury them at home or wherever, but they should never give up on trying to identify them,” he said.

One body never recovered included Franklin Van Valkenburgh, who served as the last captain of the USS Arizona. Despite an extensive search, all that was ever retrieved was his Annapolis class ring.

Captain Van Valkenburgh posthumously received the Medal of Honor, with a citation that mentioned his “devotion to duty … extraordinary courage, and the complete disregard of his own life.”

His grave can be found at Forest Home Cemetery. Technically, it is a cenotaph – a grave where the body is not present. Captain Van Valkenburgh spent his youth growing up in Milwaukee, until he left for the U.S. Naval Academy in 1905.