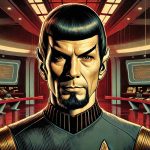

Democrats in Congress released thousands of pages of former President Donald Trump’s tax returns on December 30, providing the most detailed picture to date of his finances over a six-year period, including his time in the White House, when he fought to keep the information private in a break with decades of precedent.

The documents include individual returns from Trump and his wife, Melania, along with Trump’s business entities from 2015-2020. They show how Trump used the tax code to lower his tax obligation and reveal details about foreign accounts, charitable contributions and the performance of some of his highest-profile business ventures, which had largely remained shielded from public scrutiny.

The disclosure marks the culmination of a yearslong legal fight that has played out everywhere from the presidential campaign to Congress and the Supreme Court as Trump persistently rejected efforts to share details about his financial history — counter to the practice of transparency followed by all his predecessors in the post-Watergate era. The records release comes just days before Republicans retake control of the House and weeks after Trump announced another campaign for the White House.

The records show how Trump limited his tax liability by offsetting his income against corporate losses as well as millions of dollars in business expenses, asset depreciation and other deductions.

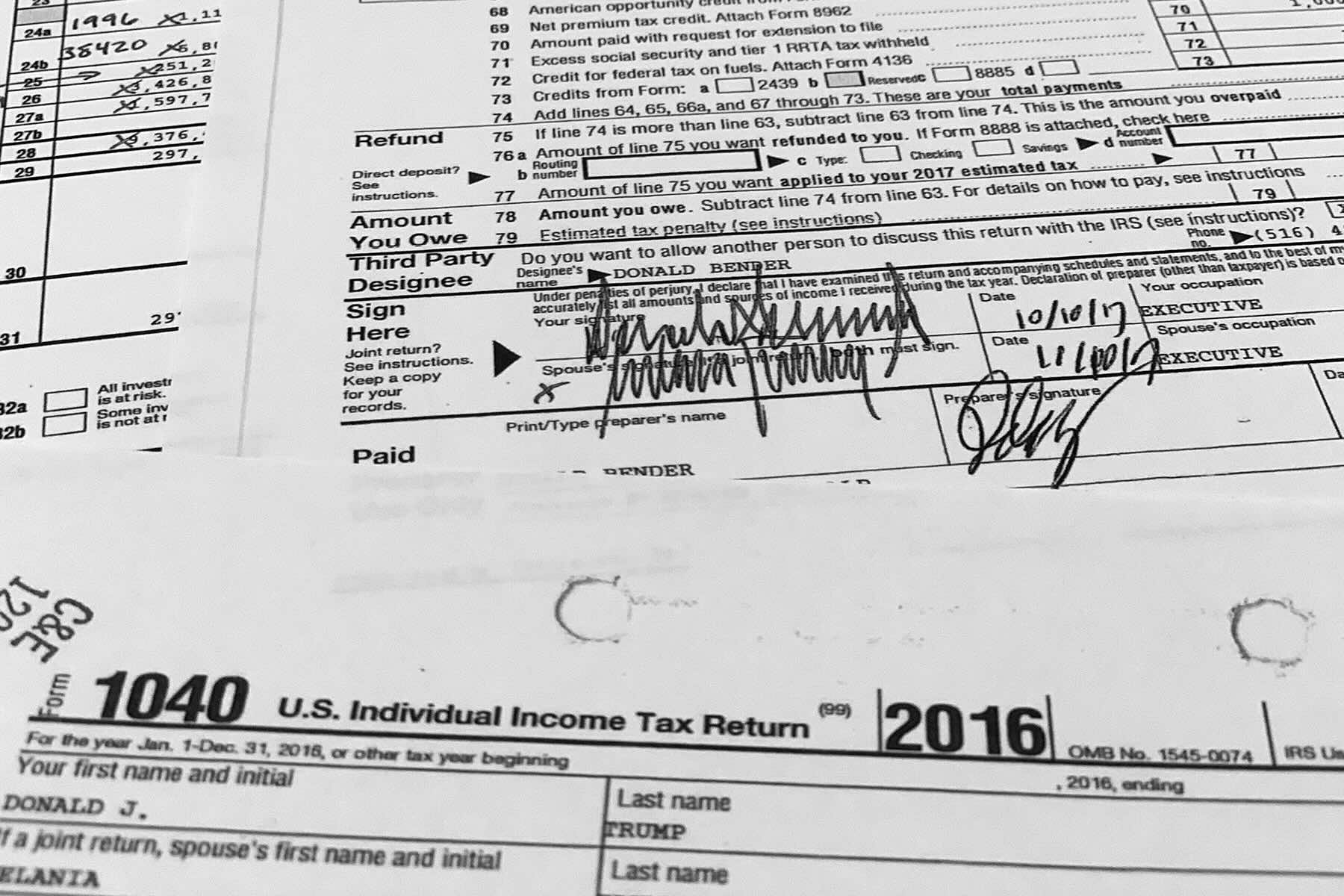

While Trump paid $641,931 in federal income taxes in 2015, the year he began his campaign for president, he paid just $750 in 2016 and 2017, according to a report released last week by Congress’ nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation. He paid nearly $1 million in 2018, but only $133,445 in 2019 and nothing in 2020, the year he unsuccessfully sought reelection. The records also detail Trump’s foreign holdings.

Trump, according to the filings, reported having bank accounts in China, Ireland and the United Kingdom in 2015 through 2017, even as he was commander in chief. Starting in 2018, however, he only reported an account in the U.K. The returns also show that Trump claimed foreign tax credits for taxes he paid on various business ventures around the world, including licensing arrangements for use of his name on development projects and his golf courses in Scotland and Ireland.

In several years, Trump appears to have paid more in foreign taxes than he did in net U.S. federal income taxes, with income reported in countries including Azerbaijan, China, India, Indonesia, Panama, the Philippines, St. Martin, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates.

The documents also show that Trump’s charitable donations often represented only a sliver of his income. In 2020, the year the coronavirus ravaged the economy, Trump reported no charitable donations at all. In 2019 and 2018 he reported writing checks for about $500,000 in donations. In earlier years the numbers were higher — $1.8 million in 2017 and $1.1 million in 2016.

It is unclear whether the reported sums included Trump’s $400,000 annual presidential salary, which he had said, as a candidate, that he would forgo and which he claimed he donated to various federal departments.

Jeff Hoopes, an accounting professor at the University of North Carolina’s Kenan-Flagler Business School, described Trump’s returns as “large and complicated” with “hundreds of entities scattered all over the globe.”

He noted that many of those entities are slightly unprofitable, which he described as “pretty magical as far as the tax code.”

“It’s hard to know if someone’s really bad at business or really good at tax planning, because they both look like the same thing,” he said.

Daniel Shaviro, a taxation professor at New York University, cited the large financial losses from so many of Trump’s businesses, despite their often healthy sales, as something that should raise suspicions from auditors. “There’s fishy looking stuff here.”

Shaviro also cited examples of suspicious or sloppy math even in smaller businesses, such as an aviation firm dubbed “DT Endeavor I LLC,” which in 2020 reported both sales and expenses of $160,144. Such exact matches are unusual, Shaviro said. Yet the form also reported an $18,923 loss.

“The return doesn’t say, ‘Guess what? I’m committing fraud,'” Shaviro said, “but there are red flags.”

The release marks the latest setback for Trump, who has been mired in investigations, including federal and state inquiries into his efforts to overturn the 2020 election. The Department of Justice also has been investigating reams of classified documents found at his Mar-a-Lago club and possible efforts to obstruct the investigation.

The returns were released by the House Ways and Means Committee, which held a party-line vote last week to make the returns public after years of legal wrangling.

The returns detail how Trump used tax law to minimize his liability, including carrying forward massive losses from previous years. Trump said during his 2016 campaign that paying little or no income tax in some years “makes me smart.”

In 2020, more than 150 of Trump’s business entities listed negative qualified business income, which the IRS defines as “the net amount of qualified items of income, gain, deduction and loss from any qualified trade or business.” In total for that tax year, combined with nearly $9 million in carryforward loss from previous years, Trump’s qualified losses amounted to more than $58 million.

Another of Trump’s money losers: the ice rink his company operated until last year in New York City’s Central Park. Trump reported a total of $2.6 million in losses from Wollman Rink over the six years made public. The rink, an early Trump Organization jewel run through a contract with New York City’s government, reported a loss of $1.3 million in 2015 despite taking in $9.3 million in revenue, according to the tax returns. The rink turned a $298,000 profit in 2016, but was back to melting cash in each of the next four years.

“Trump seems to be creating huge losses that are suspicious or questionable under current law,” said Steven Rosenthal, a senior fellow at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center, who said he had spent 20 years preparing taxes for corporations and wealthy individuals and “never saw anyone lose money as regularly and as large as Trump lost money year after year.”

“To me, Trump’s business operations were phenomenally unsuccessful and I struggle to figure out how much of it is attributable to Trump’s unluckiness as a businessman and how much of it is attributable to Trump’s inflation,” he said.

Aspects of Trump’s finances had been shrouded in mystery since his days as an up-and-coming Manhattan real estate developer in the 1980s.

Trump, known for building skyscrapers and hosting a reality TV show before winning the White House, did offer limited details about his holdings and income on mandatory disclosure forms and financial statements he provided to banks to secure loans and to financial magazines to justify his ranking on lists of billionaires.

Trump’s longtime accounting firm has since disavowed the statements, and New York’s attorney general has filed a lawsuit alleging Trump and his Trump Organization fraudulently inflated asset values on the statements. Trump and his company have denied wrongdoing.

In October 2018, The New York Times published a Pulitzer Prize-winning series based on leaked tax records that contradicted the image Trump had tried to sell of himself as a self-made businessman. It showed that Trump received a modern-day equivalent of at least $413 million from his father’s real estate holdings, with much of that money coming from what the Times called “tax dodges” in the 1990s.

A second series in 2020 showed that Trump paid no income taxes at all in 10 of the previous 15 years because he generally lost more money than he made. In its report last week, the Ways and Means Committee indicated the Trump administration may have disregarded a requirement mandating audits of a president’s tax filings.

The IRS only began to audit Trump’s 2016 tax filings on April 3, 2019 — more than two years into his presidency — when the Ways and Means chairman, Rep. Richard Neal, D-MA, asked the agency for information related to the returns. Every president and major-party candidate since Richard Nixon has voluntarily made at least summaries of their tax information available to the public.

A summary of the key takeaways from a review of the documents:

A BANK ACCOUNT IN CHINA

The longtime real estate and media mogul with business interests on multiple continents was asked during a 2020 presidential debate about having a bank account in China. He said he closed it before he began his 2016 campaign — a statement his tax returns show was not true.

“The bank account was in 2013. It was closed in 2015, I believe,” Trump said during the debate. “I was thinking about doing a deal in China. Like millions of other people, I was thinking about it. I decided not to do it.”

The tax returns, however, report that Trump had a bank account in China in 2015, 2016 and 2017.

The returns show accounts in other foreign countries over the years, including the United Kingdom, southern Ireland and the Caribbean island nation of St. Martin. By 2018, Trump had apparently closed all his overseas accounts other than the one in the U.K., home to one of his flagship golf properties. The returns do not detail the amount of money held in those accounts.

MANY FOREIGN INVESTMENTS

China is one of several countries where Trump reported making money over the years. He reported $38 million in overseas gross income in 2016 and $55 million in 2017, from countries including Azerbaijan, India, Indonesia, Panama, the Philippines, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates. This sort of information about potential conflicts of interest for the commander-in-chief of the United States are one reason presidents normally release their tax returns.

It is not clear what that overseas money came from. Trump claimed tens of millions of dollars in losses and expenses in his overseas investments as well, but his liabilities there sometimes were greater than those in the U.S. In 2016, for example, Trump told the Internal Revenue Service that he paid $1.2 million in foreign taxes, while he ended up paying only $750 in U.S. income taxes.

WORKING THE SYSTEM

It has been long known that Trump, like many rich people, has been able to exploit the country’s complex tax code to avoid paying as large a share of his income to the federal government as working families do. When he was pressed on not paying federal taxes in a 2016 debate against Democrat Hillary Clinton, Trump retorted, “That makes me smart.”

It also highlights the two-tier tax system that allows wealthy people like Trump to take advantage of breaks and loopholes not available to regular households. In 2020, for example, Trump reported owning more than 150 private corporations that claimed losses, sometimes in the millions of dollars. Partly by claiming those losses, Trump reduced his own federal tax income liability to zero that year.

Some of those losses were real as the coronavirus pandemic battered the economy. But others reflect special deductions that developers like Trump can take on the depreciation of buildings and equipment.

Some losses Trump claimed may be more questionable — one of the companies he reported owning is called “Unreimbursed expenses.” The Joint Committee on Taxation noted that one of Trump’s firms claimed $438,000 in losses for gift cards redemptions and urged additional investigation of whether the losses were genuine — one of a number of deductions into which the Democratic-controlled committee called for further investigation.

They are the sort of deductions the typical American household, which earns $70,000 a year, cannot take.

NO REPORTED CHARITABLE GIVING IN 2020

In the final year of his presidency, Trump reported making no charitable donations.

That was in contrast to the prior two years, when Trump reported making about $500,000 worth of donations. It’s unclear whether any of the figures include his pledge to donate his $400,000 presidential salary back to the U.S. government.

Trump, who has bragged of being a billionaire, told The Associated Press in 2015 that he gives “to hundreds of charities and people in need of help.”

He said, “It is one of the things I most like doing and one of the great reasons to have made a lot of money.”

He reported larger donations in 2016 and 2017, donating $1.1 million in the year he won the presidency and $1.8 million in his first year in office.

MONEY FROM THE ARTS WORLD

Trump collected a $77,808 annual pension from the Screen Actors Guild, as well as a $6,543 pension in 2017 from another film and TV union, and reported acting residuals as high as $14,141 in 2015, according to the tax returns.

Trump has made cameo appearances in various movies, notably “Home Alone 2: Lost in New York,” but his biggest on-screen success came with his reality TV shows “The Apprentice” and “The Celebrity Apprentice,” where each episode would end in a boardroom setting with Trump dismissing a contestant with his trademark phrase: “You’re fired!”

Trump also reported paying a little more than $400,000 from 2015 to 2017 in “book writer” fees. In 2015, Trump published the book, “Crippled America: How to Make America Great Again,” with a ghostwriter.

In 2015, Trump reporting receiving $750,000 in fees for speaking engagements.

TRUMP VOWS PAYBACK

Trump broke political tradition by not releasing his tax returns as president. Now Republicans warn that Democrats will pay a political price by releasing what is normally confidential tax information.

Republicans on the House Ways and Means Committee, which has jurisdiction over tax matters and released the Trump documents, warned that in the future the committee could release the returns of labor leaders or Supreme Court justices. Democrats countered with a proposal to require the release of tax returns by any presidential candidate — legislation that is unlikely to pass with Republicans in control of the House.

Notably, the GOP cannot disclose President Joe Biden’s tax returns because they are already public. Biden resumed the long-standing bipartisan tradition of releasing his tax records, disclosing 22 years’ worth of his filings during his presidential campaign.