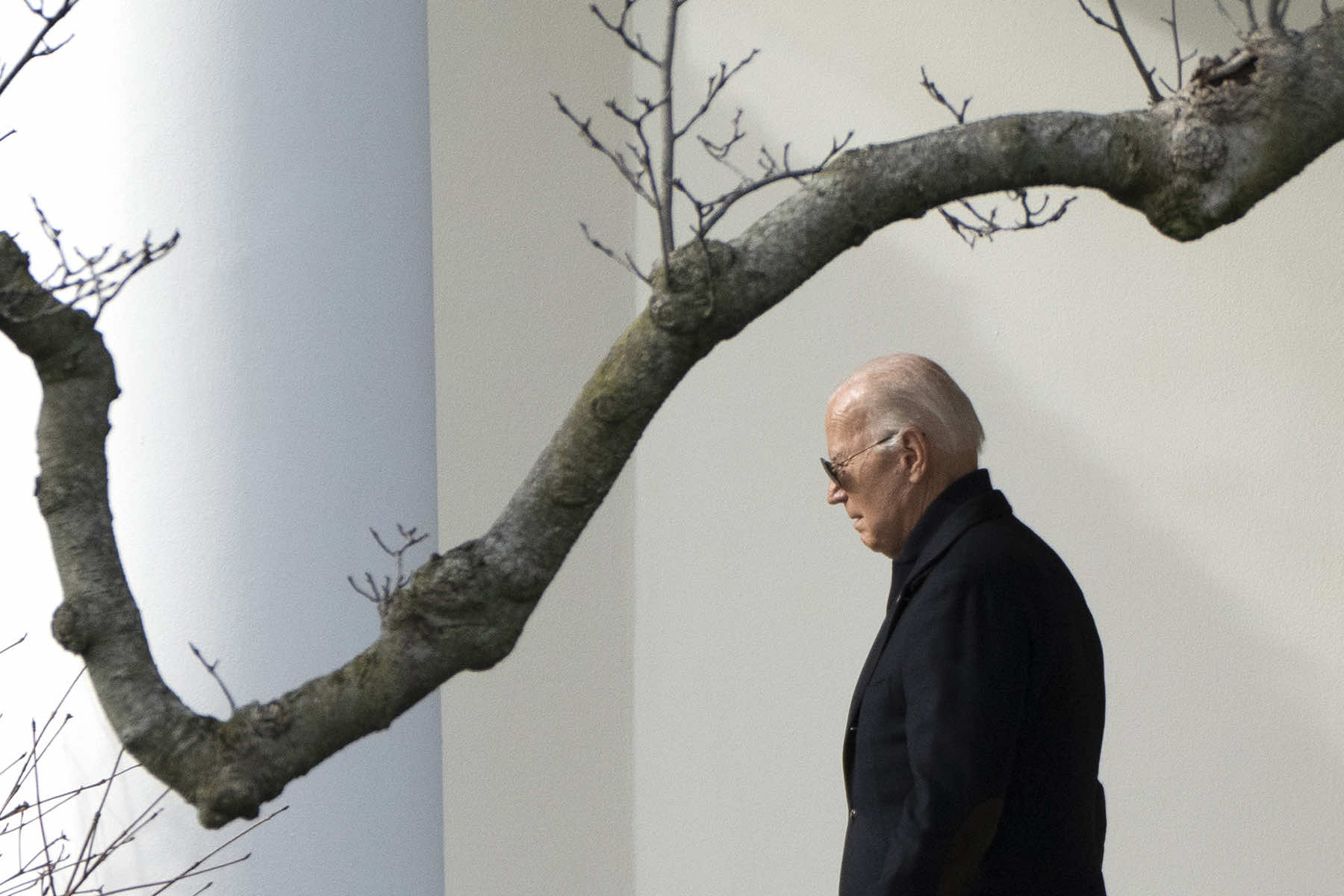

How it began: President Joe Biden was urgently seeking more money from Congress to aid Ukraine and Israel. He took a gamble by seizing on GOP demands to simultaneously address one of his biggest political liabilities, illegal migration at the Mexico-U.S. border.

How it ended: Biden came close to succeeding, before it all fell apart spectacularly. Now the president is trying to make the best of it after a major congressional deal was scuttled once Republican front-runner Donald Trump got involved. And Biden is intent on showing that the former president and his “Make America Great Again” Republican acolytes in Congress aren’t really interested in solutions.

In between: There is a story of a president willing to anger his own party’s activist class in an election year, rare hope for bipartisan progress on one of the third rails of American politics, and a sudden, stunning collapse publicly engineered by Trump that Biden’s team now sees as a political gift.

This account of Biden’s big gamble is based on interviews with more than a dozen White House aides, lawmakers, Biden administration officials and congressional aides, some of whom spoke to The Associated Press on condition of anonymity to discuss the back and forth over the collapsed deal, and what happens next.

The bipartisan legislative deal announced on February 4 was the culmination of more than four months of negotiations that started with Senate Democrats and Republicans, and later included top Biden aides and Cabinet officials. It came after Republicans, led by then-House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, backed a temporary spending deal that kept the government operating but delivered no new funding for Ukraine.

McCarthy had insisted to the White House that any effort to continue U.S. funding for Ukraine needed to be linked to significant steps to secure the Mexico-U.S. border, long a GOP priority. Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, Biden’s most valuable Republican ally when it came to Ukraine aid, also began appealing to senior administration officials for the spending measure to include border provisions.

Inside the White House, there was no shortage of grumbling that Republicans were insisting on unrelated policy changes and holding up badly needed money for the Ukrainian armed forces.

But Biden and his advisers saw a potential upside as well, at a time when the president’s handling of immigration was one of his biggest political vulnerabilities and there were chaotic scenes at the border and in major Democratic-run cities where migrants are sleeping in police station foyers, bus stations and hotels.

Before long McCarthy was ousted and it took weeks to elect a replacement. New House Speaker Mike Johnson, elected October 25, made clear that he, too, wanted to pair border security with any new Ukraine funding.

While the House was in disarray, a group of bipartisan senators quietly got to work.

The White House kept its distance until senior officials felt it was the right time to get directly involved, but there was also pressure from Republicans for them to join the talks. GOP lawmakers insisted it was necessary for Biden to expend some political capital and embrace a border compromise that could be unpopular with parts of his own party.

On Dec. 12, the White House dispatched senior officials, including Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas, to join the negotiations. The idea was to underscore Biden’s seriousness about cutting a deal with Republicans.

“Immediately after the Republicans demanded that the administration show up, they showed up,” said Sen. Chris Murphy, D-CT, one the negotiators.

Difficult negotiations stretched into 2024. But there were signs of progress and Biden was optimistic. So much so that on January 18, he said he didn’t think there were any sticking points left.

In an effort to push the bill forward, Biden even adopted Trump’s own language saying he’d “shut down the border” if given the power — a stunning admission from a Democrat that was quickly and loudly condemned by activists in his own party.

The deal that emerged would have overhauled the asylum system to provide faster and tougher immigration enforcement, as well as given presidents new powers to immediately expel migrants if authorities become overwhelmed with the number of people applying for asylum. It also would have added $20 billion in funding, a huge influx of cash.

It was never entirely clear what the White House strategy was to advance the border compromise in the House should it make it out of the Senate. Johnson repeatedly voiced resistance to how the agreement was shaping up. Asked why the administration was choosing to hash out a deal with the Senate and not the House, White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre regularly pointed out that House Republicans left for the holidays in mid-December while talks were ongoing.

House Armed Services Committee Chairman Mike Rogers, R-AL, said it was a mistake that the White House didn’t negotiate with House Republicans directly, but that even so, if the deal “actually sealed the border, it could’ve sailed through.”

Enter the former president. He had been occupied for weeks by a defamation trial in New York City and fending off GOP challenges from Ron DeSantis and Nikki Haley in Iowa and New Hampshire.

At a rally in Nevada on January 27 — after solidifying his position as the far and away GOP front-runner — he said his piece: “As the leader of our party, there is zero chance I will support this horrible open borders betrayal of America. I’ll fight it all the way.”

“A lot of the senators are trying to say, respectfully, they’re blaming it on me,” Trump added, followed by the 10 words that made Biden aides light up: “I say, that’s OK. Please blame it on me. Please.”

By the time the text of the bill was released on February 4, the pile-up of Republicans willing to block it already appeared insurmountable. GOP lawmakers claimed Biden already could fix the situation at the border with existing authority. But some in Congress publicly echoed Trump in saying they didn’t want to give Biden a political win on an issue that they see as key to their 2024 hopes.

With that, the deal that the White House and many in the Senate thought would pass was headed for failure. In a stern address this week, the president vowed to make sure that voters understand why it foundered.

“I’ll be taking this issue to the country, and the voters are going to know that just at the moment we were going to secure the border and fund these other programs, the MAGA Republicans said ‘no’ because they’re afraid of Donald Trump,” Biden said.

The rapid collapse of Republican backing for the border compromise stunned even those who worked most closely on the agreement. Murphy said that even by February 4, he had counted 20 to 25 GOP senators as potential votes in favor of the deal.

“I am still shocked at how every single one of these Republicans, including many Republicans that were like, literally in the room with us – like, hours after helping us try to get the final product, they were declaring they were against it,” Murphy said. “I’ve never seen anything like this in my time in Washington.”

To Biden aides, it was public validation of the argument the president had been making about Trump and his allies — that they had their own interests at heart, not the country’s.

Even in failure, the bipartisan agreement in principle was the closest Washington has come to significant revisions to border policy in two decades. And Biden allies are intent on making Republicans take the hit for any further scenes of chaos at the border.

It is far from assured that Biden’s efforts to pin the blame on Trump will stick. His GOP critics will no doubt continue their relentless efforts to saddle the current Oval Office occupant with the country’s immigration woes. And the president still has to contend with sore feelings among progressive Democrats who feel the president sold them out by going all-in on tougher measures and language that had previously been a nonstarter for the party.

Biden, though, has his plan: “Every day between now and November, the American people are going to know that the only reason the border is not secure is Donald Trump and his MAGA Republican friends.”