Days after Russian forces withdrew from the outskirts of Kyiv in the dramatic first weeks of their full-scale invasion two years ago, a photo revealed what had become of Nataliia Verbova’s missing husband.

Poring over the image of eight men executed and lying on cold concrete in the suburb of Bucha, taken by AP photographer Vadim Ghirda, she focused on a man face down with his hands tied. She did not want to believe it was Andrii, who had joined the territorial defense days after the invasion but was detained by the Russians.

A month later, she visited the morgue and recognized the socks she had gifted him. It was Andrii.

“I will never forget the pool of blood under him. When I saw these photos all around the world I felt pain,” she said, standing over her husband’s grave. “Two years have passed, but for me it’s as though it happened yesterday. Nothing has changed.”

Russian troops quickly occupied Bucha after invading Ukraine and stayed for about a month. When Ukrainian troops retook the town, they found what became known as the epicenter of the war’s atrocities.

Dozens of bodies of men, women, and children lay on the streets, in yards and homes, and in mass graves. Some showed signs of torture. Day after day, body collectors found the dead in basements, lying in doorways, deep in the woods. The once comfortable suburb was shocked and silent.

More than 400 bodies were found. Ukrainian authorities say the total number of dead has not been finalized, with many still missing.

Today, two years on, Bucha is evolving. Cranes dot the horizon and the skeletal frames of future residential complexes line the main thoroughfare. Cafes and restaurants are open. They are signs of hope and renewal where there was once only trauma and despair.

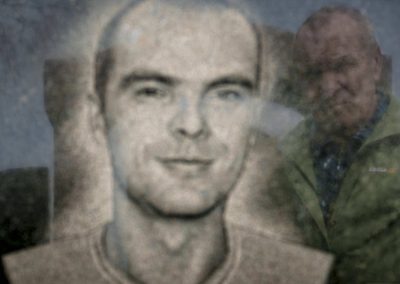

Where hurried graves had been marked with wooden crosses, there are now marble tombstones with the portraits of war heroes.

In the neighboring suburb of Irpin, where entire streetscapes were shattered and blackened under Russian occupation, what was destroyed is being reconstructed.

To mark the second anniversary of the liberation of these and other Kyiv suburbs, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy thanked all those involved in their renewal.

“This is about more than just rebuilding from the ruins; it is about preserving the idea of a free world and our united Europe,” said President Zelenskyy.

But for those who suffered the worst of Russian atrocities, such changes are cosmetic. For those Bucha residents, time has not dulled the pain of loss. Many are struggling to come to terms with what happened to them and their loved ones.

Verbova is grateful her husband has received a more permanent resting place.

He and the other men had set up a roadblock in an attempt to prevent Russian troops from advancing as they swept toward Kyiv. They were later discovered by Ghirda, the AP photographer, lying outside a building on Yablunska Street.

They had been there for a month, their sprawled bodies preserved by the winter cold. Only after the Russians pulled out of Bucha could their loved ones collect them.

The men should be considered national heroes, Verbova said. She holds on to her husband’s possessions — his telephone book and wallet — as if they were jewels.

But she cannot move on. She said the government has not given her husband official status as military personnel, a designation that would enable the family to receive financial compensation.

It is a problem most of the men’s families share. Oleksandr Turovskyi, whose 35-year old son Sviatoslav was among them, is fighting to get him the same status. At home, where photos of Sviatoslav as a boy and as a member of the territorial defense are on display, he holds up his son’s war medals.

“Parents should not bury their children. It’s not fair,” he said.

Unlike much of reviving Bucha, the place where the eight men were discovered is mostly untouched. Their portraits hang on the building’s wall along with flowers.

Turovskyi still visits the scene to feel closer to his son.

“At 5 o’clock in the evening (after work), I still have a feeling that he will come in and say: ‘Hello, how are you?’” he said. “All these two years, even more than two years, I have been waiting for him. Although I know that I have already buried him, I am still waiting.”

The world should not forget that there is a war in Ukraine, he said.

“That’s why we have to talk about it, in order to stop it and prevent it from spreading,” he said. “So that others cannot feel what we feel.”

The empty plot in a courtyard where in 2022 Russian forces left the dead bodies of eight men, photographed from the same angle than a photo taken by AP photographer Vadim Ghirda in April 2022 in Bucha, Ukraine, March 30, 2024. The photo showed bodies of men, some with their hands tied behind their backs, lying on the ground. It was part of a series of images by Associated Press photographers that was awarded the 2023 Pulitzer Prize for Breaking News Photography.