As more than 100,000 migrants arrived in New York City over the past year after crossing the border from Mexico, Mayor Eric Adams and Governor Kathy Hochul have begged President Joe Biden for one thing, above all others, to ease the crisis.

“Let them work,” both Democrats have said repeatedly in speeches and interviews.

Increasingly impatient leaders of Biden’s party in other cities and states have hammered the same message over the last month, saying the administration must make it easier for migrants to get work authorization quickly, which would allow them to pay for food and housing.

But expediting work permits isn’t so easy, either legally or bureaucratically, experts in the process say. Politically, it may be impossible.

It would take an act of Congress to shorten a mandatory, six-month waiting period before asylum-seekers can apply for work permits. Some Democratic leaders say the Biden administration could take steps that wouldn’t require congressional approval. But neither action seems likely.

Biden already faces attacks from Republicans who say he is too soft on immigration, and his administration has pointed to Congress’ inability to reach an agreement on comprehensive changes to the U.S. immigration system as justification for other steps it has taken.

The Homeland Security Department has sent more than 1 million text messages urging those eligible to apply for work permits, but it has shown no inclination to speed the process. A backlog of applications means the wait for a work permit is almost always longer than six months.

As frustrations have mounted, Hochul has said her office is considering whether the state could offer work permits, though such a move would almost certainly draw legal challenges. The White House has dismissed the idea.

Immigrants are frustrated as well. Gilberto Pozo Ortiz, a 45-year-old from Cuba, has been living, at taxpayer expense, in a hotel in upstate New York for the last three months. He says his work authorization is not yet in sight as social workers navigate him through a complex asylum application system.

“I want to depend on no one,” Ortiz said. “I want to work.”

In Chicago, where 13,000 migrants have settled in the last year, Mayor Brandon Johnson and Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker wrote Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas to ask for parole for asylum-seekers, which, they say, would allow him to get around the wait for a work permit.

Massachusetts Governor Maura Healey, who declared a state of emergency over the migrant influx, wrote Mayorkas that work permits represent “an opportunity to meet employer needs, support our economy, and reduce dependency among new arrivals.” And 19 Democratic state attorneys general wrote Mayorkas that work permits would reduce the strain on government to provide social services.

The federal government has done “virtually nothing” to assist cities, said Chicago Alderman Andre Vasquez, chair of the City Council’s Committee on Immigrant and Refugee Rights.

In the meantime, migrants unable to get work permits have filled up homeless shelters in several cities.

With more than 60,000 migrants currently depending on New York City for housing, the city has rented space in hotels, put cots in recreational centers and erected tent shelters — all at government expense. The Adams administration has estimated that housing and caring for migrants could cost the city $12 billion over three years.

“This issue will destroy New York City,” Adams said at a community event this month. “We’re getting no support on this national crisis, and we’re receiving no support.”

Advocates for migrants have objected to Adams’ apocalyptic terms, saying he is exaggerating the potential impact of the new arrivals on a city of nearly 8.8 million people.

Republicans have seized on the discord, putting Democrats on the defensive ahead of next year’s presidential elections.

Muzaffar Chishti, a lawyer and senior fellow at the Migration Policy Institute, said the calls for expedited work authorizations are more about political optics than practical solutions.

“They don’t want to tell the electorate there’s nothing we can do. No politician wants to say that. So they have kind of become the new squeaky wheel, saying, `Give us work authorization,'” he said. “Saying that is much easier than getting it. But it’s sort of, you know, a good soundbite.”

One step that most agree would be helpful is to provide legal assistance to migrants to apply for asylum and work authorization, though that has also proved challenging.

Nationwide, only around 16% of working age migrants enrolled in a U.S. Custom and Border Protection online app have applied for work permits, according to the White House. Since the introduction of the CBP One app in January through the end of July, nearly 200,000 asylum-seeking migrants have used it to sign up for appointments to enter the U.S. at land crossings with Mexico.

Federal officials recently began sending email and text message notifications to remind noncitizens that they are eligible to apply. New York City officials have also begun to survey asylum seekers to determine if they are eligible.

Another option would be to expand the number of nations whose citizens qualify for Temporary Protected Status in the U.S. That designation is most commonly given to places where there is an armed conflict or natural disaster.

The White House, though, might be reluctant to take steps that could be interpreted as incentivizing migrants to come to the U.S.

Arrests from illegal border crossings Mexico topped 177,000 in August, according to a U.S. official who was not authorized to discuss unpublished numbers, up nearly 80% from June. Many are released in the U.S. to pursue asylum in immigration court, while an additional 1,450 migrants are permitted into the U.S. daily through CBP One.

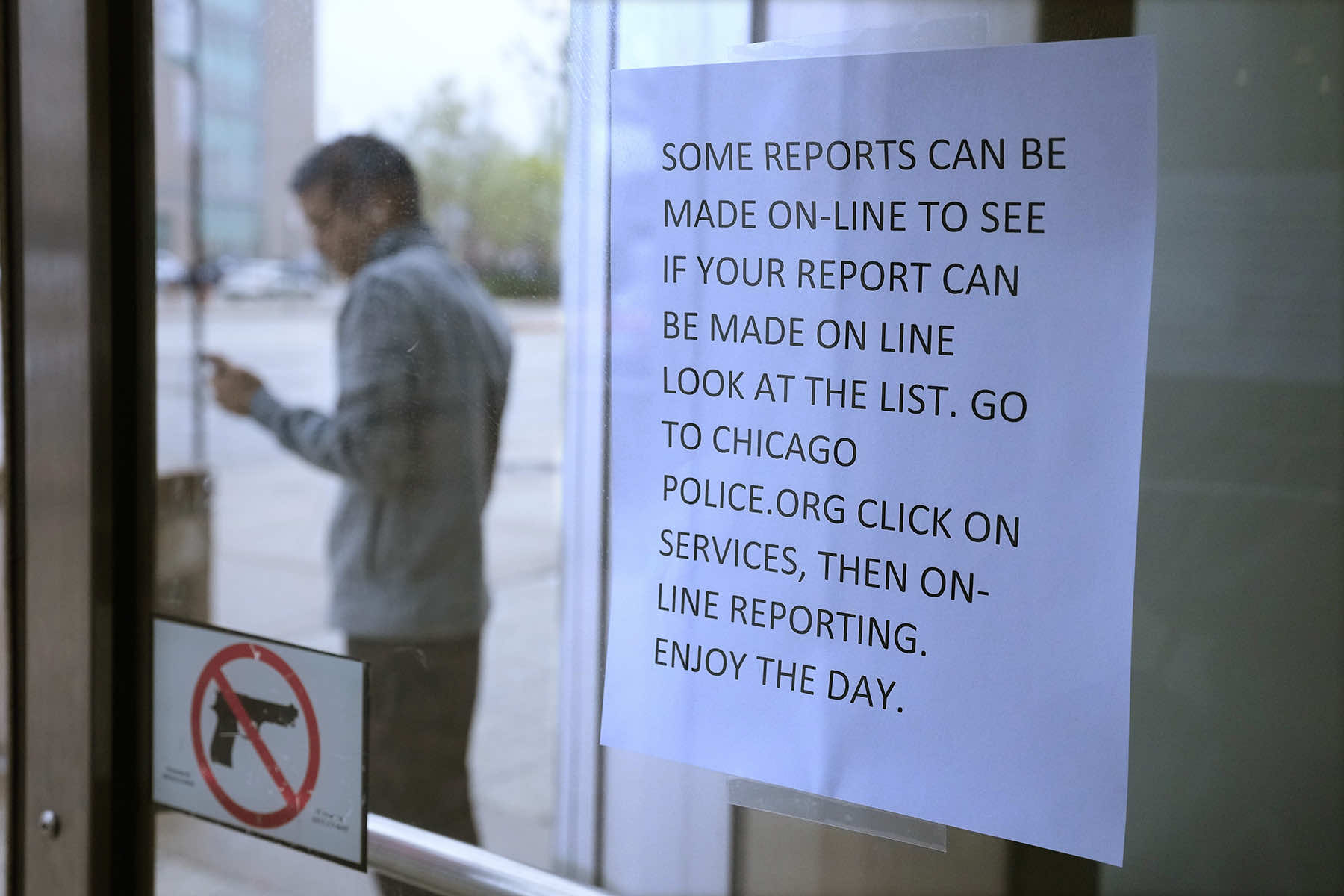

Many have gravitated to an underground economy.

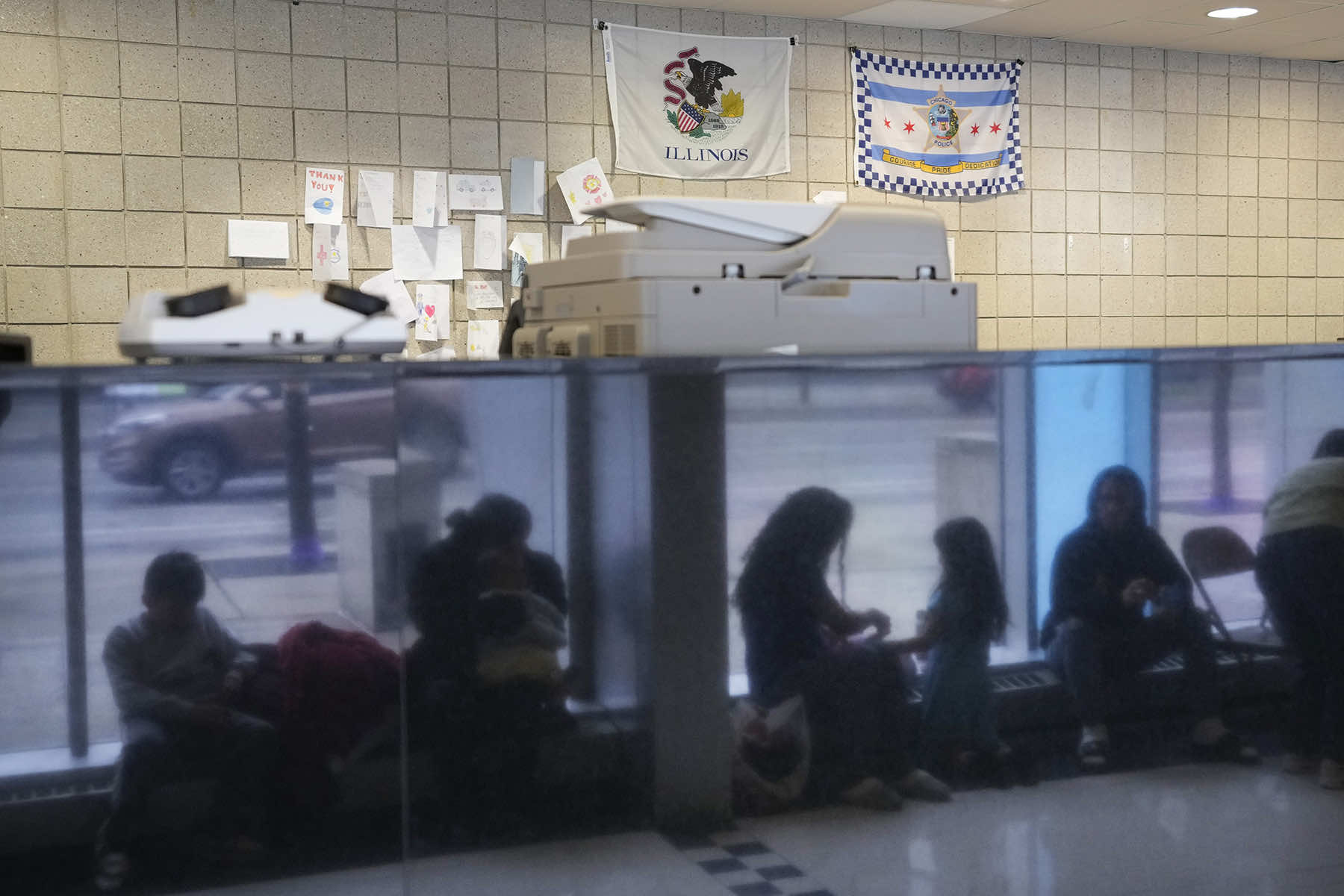

Elden Roja, who has been sporadically working landscaping and other odd jobs for about $15 an hour, lives with his wife and children, 15 and 6, and about 50 others in a police station lobby in Chicago. When a fellow Venezuelan co-worker honked from a car he purchased, Roja laughed and said he would buy his own vehicle soon.

While the bureaucratic hurdles can be substantial, many migrants do make it through the process.

Jose Vacca, a Venezuelan, traveled with two of his cousins from Colombia, leaving their families behind to make the journey mostly by foot. Once in Texas, he was given free bus tickets to New York City.

The 22-year-old found a job there that paid him $15 an hour, under the table. After he got his temporary work authorization, his boss gave him an extra dollar per hour.