Thelma Sims Dukes grew up during the 1940s and 1950s in a segregated Mississippi town steeped in Civil War history.

As a small Black girl, she would walk to school through Vicksburg National Military Park — the hilly battlefield where Union and Confederate soldiers fought and died over whether the U.S. would continue allowing slavery in the South.

Union forces won a pivotal campaign to capture the town of Vicksburg and gain control of the Mississippi River in 1863, hastening the war’s end. But during Dukes’ childhood, Vicksburg venerated the Confederacy and ignored the history of Black soldiers who fought for the Union, including her great-great-grandfather, William “Bill” Sims.

“The superintendents and the museum curators — they said we didn’t fight in the Civil War,” Dukes said recently.

The Black soldiers’ valor and service to the country is no longer ignored, thanks to the efforts of historians, park employees and citizens like Dukes. On crisp morning in mid-February, Dukes and her niece, Sara Sims, and four park employees — two of them Black men wearing reproductions of U.S. Army uniforms from the Civil War — placed American flags on 13 graves where recently identified Black soldiers are buried in Vicksburg National Cemetery, which is part of the military park.

A historian working for the military park, Beth Kruse, identified the soldiers through research of military records, newspapers and other sources. Their remains lie beneath white marble headstones carved with numbers rather than names, as are most veterans buried in the cemetery.

In recent years, the National Park Service has broadened how it presents history in parks nationwide. The Vicksburg military park, which is dotted with more than 1,400 monuments, markers and tablets, and is one of the largest tourist attractions in Mississippi, drawing visitors from around the globe. Its visitor center now includes information about Black history, and a monument to Black soldiers was dedicated 20 years ago.

Sunlight dappled the graves under a towering magnolia tree during the flag-planting ceremony on February 14. Dukes said the men and other Black Union soldiers were “freedom fighters,” not only for themselves but for all Americans.

“They are not unknowns anymore,” she said. “This is a start. This is good. Let’s put history right.”

The newly identified soldiers had enlisted in the Vicksburg-based 1st Mississippi Infantry (African Descent) as the town was under federal occupation. In early 1864, 18 soldiers and two white officers traveled by boat some 95 miles (153 kilometers) north along the Mississippi River to Chicot County, Arkansas, to forage for crops to feed people and horses.

On February 14, 1864, at Ross Landing near the town of Lake Village, irregular Confederate troops from Missouri shot the Union soldiers and officers, killing most and leaving some for dead. They used the Union soldiers’ own bayonets to impale the dead and wounded, pinning them to the ground, according to research by Kruse.

Brendan Wilson, chief of interpretation, education and partnerships for Vicksburg National Military Park, said on the 160th anniversary of the gruesome day in Ross Landing that it’s still not known which of the 13 Black soldiers from that massacre is in which specific grave. Records show where the group is buried.

“And now we have their names and can bring those names back to life,” Wilson said.

Kruse is working in Vicksburg through the National Park Service’s Mellon Humanities Postdoctoral Fellows program. She said at least 11 soldiers of the 1st Mississippi Infantry (African Descent) were previously enslaved on southern plantations.

“For these soldiers, it was not abstract ideology,” she said. “They knew what it was to be unfree.”

Vicksburg National Cemetery was established in 1866 and now holds more than 18,000 graves — veterans from six wars and a few former park employees. More than 17,000 of them fought for the Union in the Civil War, including more than 5,500 Black soldiers, designated by the U.S. War Department in 1863 as United States Colored Troops.

Vicksburg is the largest cemetery for Union soldiers and sailors, its dead brought from Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and other states. Nearly 13,000 are buried as unknown.

About 5,000 Confederate soldiers are buried in a city cemetery in Vicksburg, outside the military park.

Some 80 years after the Civil War ended, Dukes’ father worked in maintenance at the National Military Park. She said she has always thought the landscape of the former battlefield is beautiful, but when she was young she never saw any of the history there as relevant to the Black community.

“All I know is that the South lost. OK, I did know that,” Dukes said. “But none of the battles like we are learning now. I didn’t feel like it was any connection to Blacks.”

In 2004, Vicksburg National Military Park dedicated a monument honoring the Black soldiers who fought in the Vicksburg Campaign. The troops were pivotal in a Union victory at Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana, along the Mississippi River north of Vicksburg, in June 1863.

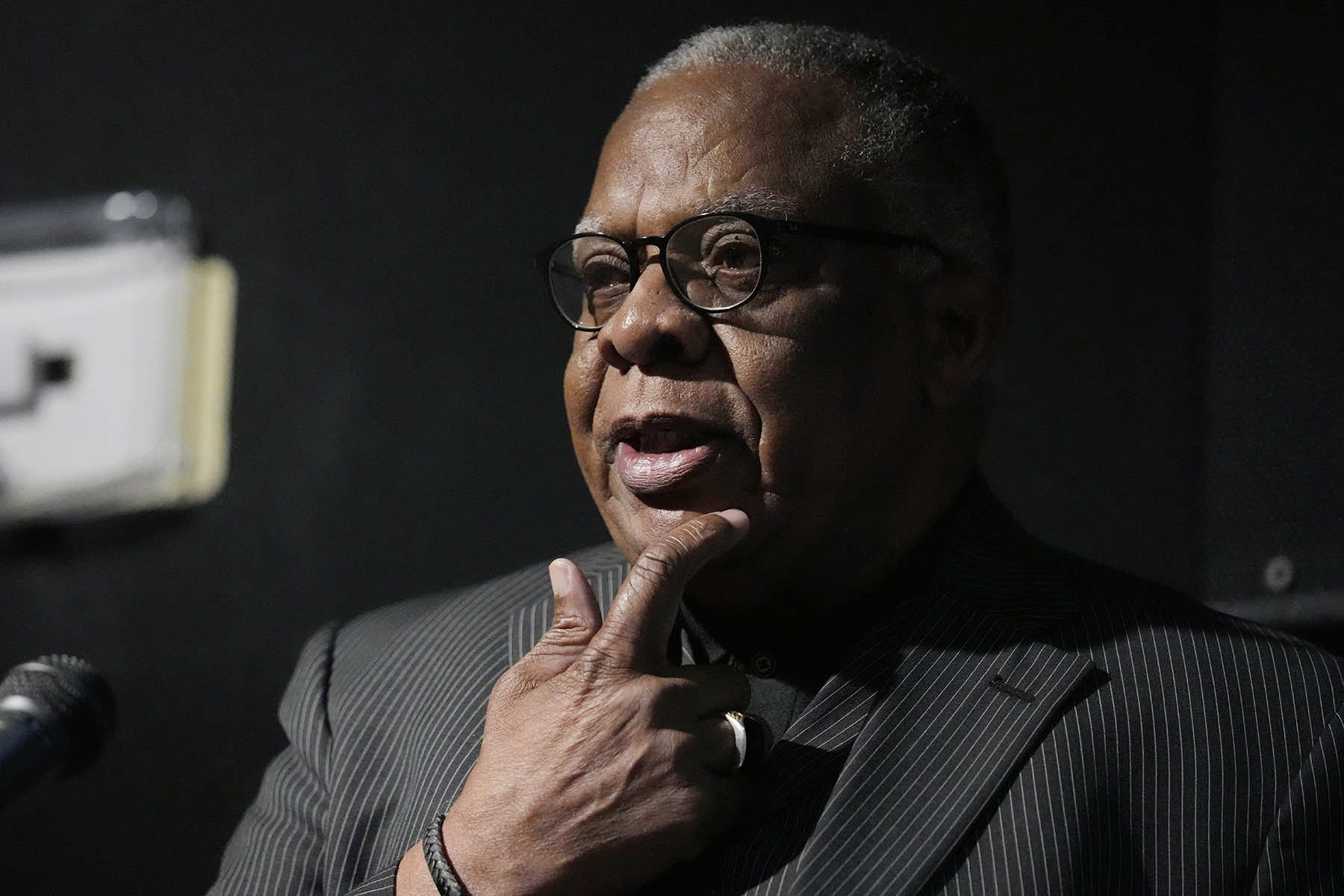

Robert Major Walker, a historian elected as Vicksburg’s first Black mayor in 1988, proposed the monument in 1999 after spending years doing research and securing money for it.

“Something had to be done to show the involvement of Black folk in the Civil War,” Walker said recently. “So much positive had been left out of the books of history. Everybody needed to know the truth.”

Dukes, whose great-great-grandfather fought at Milliken’s Bend and survived the war, criticizes efforts by some Republican governors, including Florida’s Ron DeSantis and Mississippi’s Tate Reeves, to limit the teaching about slavery and other difficult aspects of U.S. history.

“And I don’t see why the majority of people in America don’t say, ‘No, you can’t do that. Let’s tell it all,'” Dukes said.

Three days after placing American flags in the cemetery, Dukes joined others inside the military park’s visitor center for a libation ceremony, a traditional African religious ritual, to pay tribute to the 20 men killed or wounded at Ross Landing.

Albert Dorsey Jr., a history professor from Jackson State University, read the name of each man — Black and white — as he poured water into a pot of soil and grass, a small chunk of Earth brought indoors for the chilly day:

Pvt. Henry Berry, Pvt. Calvin Cathron, 1st Lt. Thaddeus Cock, Pvt. Howard Dixon, Corp. Fleming Epps, Pvt. Ruffian Epps, Corp. Peter Everman, Pvt. Charles Farrar, Pvt. Henry Ford, Pvt. John Genefa, Pvt. Anthony Givens, Pvt. Richard James, Sgt. Tony McGee, Sgt. Noah Powell, Pvt. Thomas Ransom, 1st Sgt. James Spencer, Pvt. Isaac Stanton, Pvt. Isom Taylor, Corp. Nelson Walker, Pvt. James H. Boldin.

After each name, the audience of about 50 people responded: “Asé,” pronounced ah-SHAY, a word from the Yoruba language spoken in parts of western Africa. It is similar to “Amen,” an affirmation of a life force.

The 13 Black men killed in the massacre were initially buried at Ross Landing, and later interred in the cemetery as unknowns. Three more were wounded and died during or shortly after the Civil War, and also were buried as unknowns. Two others survived until 1918. The two white officers’ bodies had been identified and sent home to Ohio and Indiana for burial during the war.

Kruse told the audience that the Black men who joined the Union Army were “not groveling for inclusion” but actively chose to fight.

“As President Lincoln remarked of the Gettysburg dead,” Kruse said, “we, too, can recognize the men who lay in the hallowed grounds of the Vicksburg National Cemetery, and never forget what they did for freedom.”