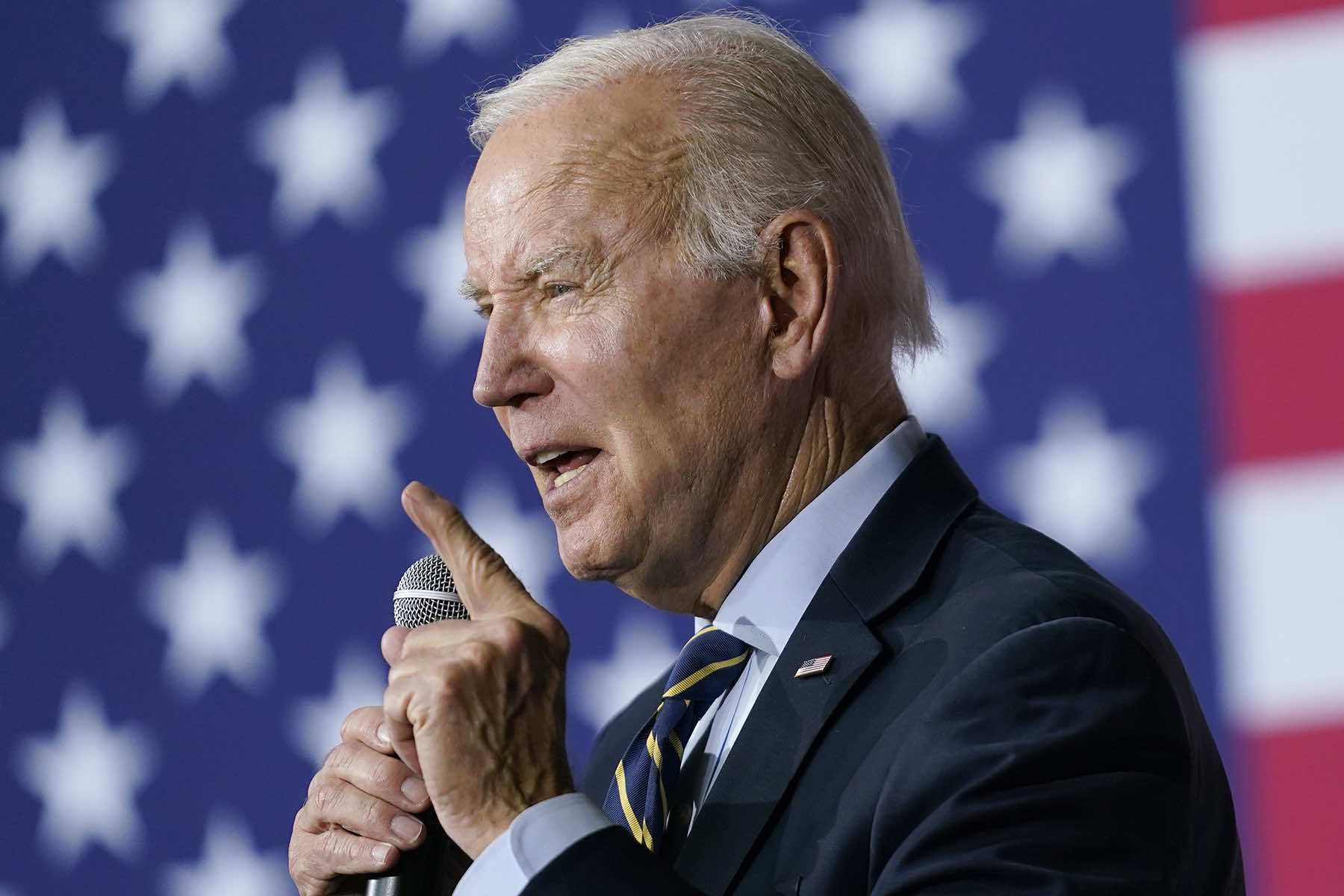

President Joe Biden lambasted Republicans’ emerging trade-off plans to raise the nation’s debt limit only in exchange for spending cuts and other policy concessions on April 19, declaring that GOP lawmakers are threatening a historic default on U.S. obligations “unless I agree to all these wacko notions they have.”

His remarks in a union hall speech came as House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, who had for months struggled to unite Republicans around a unified budget proposal, released a sweeping spending-restraint plan to offer to the White House along with lifting the debt limit by $1.5 trillion.

But it is far from settled whether McCarthy has 218 Republican votes — a House majority — in favor of his proposal, which has no chance of becoming law in the Senate and is meant to kickstart negotiations with the administration. Cruising toward crisis, if Congress and Biden can’t agree to raise the limit in coming weeks, the government would be at risk of being unable to pay its bills and facing an economy-ravaging default.

The split-screen presentations, which began with McCarthy delivering a speech on Wall Street, vividly displayed how Biden and the speaker are talking to two very different Americas.

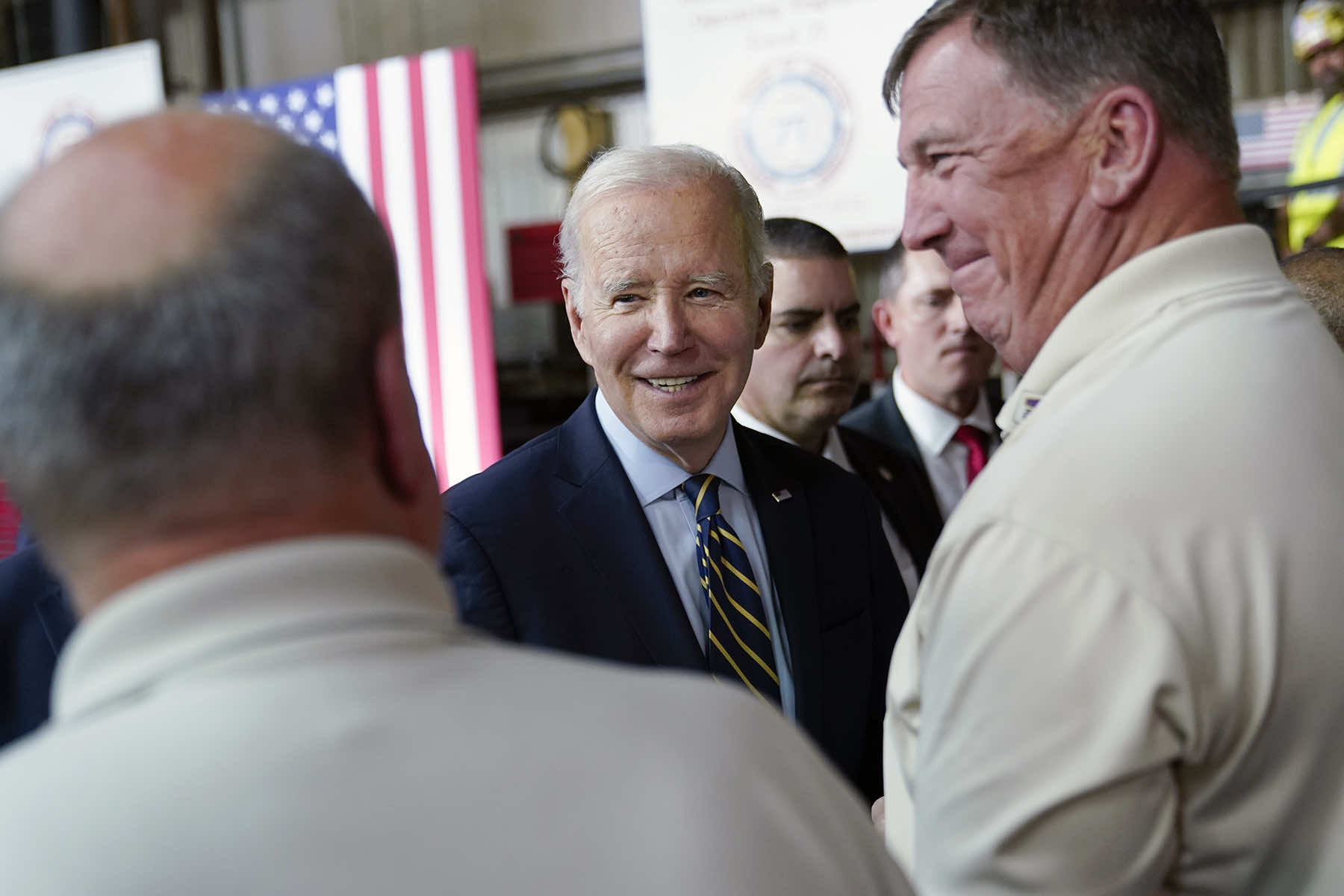

Standing in a steel garage and workshop, Biden pointedly noted the contrast, telling the members of International Union of Operating Engineers, Local 77 that while “I’m here in the union hall with you, Speaker McCarthy just got finished speaking to Wall Street two days ago.”

Biden emphasized that strictly limiting government spending programs could hurt a middle class that’s already struggling to afford basic needs. And demanding concessions in exchange for paying the nation’s debts is “worse than totally irresponsible,” Biden said, declaring that “America is not a deadbeat nation.”

“Folks, that’s the MAGA economic agenda: Spending cuts for working- and middle-class folks … with tax cuts for those at the top of the pile,” Biden said, referring to former President Donald Trump’s campaign slogan, Make America Great Again. “It’s not about fiscal discipline. It’s about cutting benefits for folks … they don’t seem to care much about.”

Commenting in kind, McCarthy said, “President Biden is skipping town to deliver a speech in Maryland rather than sitting down to address the debt ceiling.” He also insisted that House Republicans were the ones acting responsibly by insisting on reining in the federal government’s spending habits.

“If you gave your child a credit card and they kept maxing out the limit, you wouldn’t blindly raise the limit. You’d change their behavior,” McCarthy said. “The same is true with our national debt.”

The speaker took to the House floor shortly before Biden spoke on April 19 and detailed the GOP plan. It would, among other provisions, claw back billions of unspent COVID-19 relief funds, rescind money meant to boost staffing at the Internal Revenue Service, and stop Biden’s effort to cancel up to $20,000 in student loan debt for millions of borrowers.

The plan would roll back spending to 2022 levels, and impose a 1% cap on most future federal spending for the next decade. The proposed debt limit increase would last until sometime next year, putting the issue back in the spotlight during the presidential campaign.

The California Republican argues excess government spending is driving up inflation, empowers China and threatens the future of Social Security and Medicare.

Biden and McCarthy, who need to come together for the sake of the U.S. economy, are playing out diametrically opposing strategies to different audiences, each wagering he’ll win out in the end.

To the extent the two men have engaged each other — with no active negotiations so far — it has been only to provide fodder for attacks.

McCarthy says Biden is “bumbling” into a default by not meeting with him; Biden counters that McCarthy has already “threatened to become the first speaker to default on our national debt” unless he gets what he wants in the budget.

Complicating things for McCarthy, he is facing pressure not to give ground from conservatives in his razor-thin House majority who earlier this year delayed his elevation to the speakership.

But Biden contends that spending cuts would put an unacceptable strain on the government’s ability to meet its constitutional responsibility to stand behind its obligations. The GOP’s faith in tax cuts has blown up the deficit, he says.

Under the Republican proposal, the debt limit would be extended into next year, McCarthy said. He pressed the White House to negotiate a compromise with GOP lawmakers, noting that voters elected a divided Congress in the November midterms.

So far this year, he said, Biden “has been avoiding the issue for 77 straight days and counting.”

Both men are veterans of the nasty debt limit battle of 2011, when Biden was vice president and McCarthy was a relatively new member of the House Republican leadership. They know the risks of even edging close to the debt limit deadline, such as the first-ever downgrade of the U.S. credit rating that occurred that summer. For all the posturing, the markets generally assume as of now that a deal will be reached as it has in the past.

But as they’ve talked past each other, they’ve rarely talked with each other. The president and the new Republican speaker sat down in early February, but have had little substantive communication since. The White House, instead, has pushed McCarthy publicly to release a GOP budget plan that details its proposed cuts — which Democrats say are anathema to voters.

Meanwhile, the White House is standing with Democrats on Capitol Hill who overwhelmingly insist that no concessions be made in exchange for lifting the debt limit.

It’s far from clear whether McCarthy’s plan can get 218 votes — a House majority —and whether he would have to add on other changes — such as repealing the Democrats’ sweeping climate, health care and tax law known as the Inflation Reduction Act — to persuade holdout Republican lawmakers.

Much of the rhetoric now is political posturing ahead of the deadline to raise the debt limit before the U.S. reaches the ceiling, which is a moving target but is expected in the coming months. The White House has only hardened on its no-negotiation stance since Biden hosted McCarthy in the Oval Office, but most lawmakers and economists believe that eventually the two sides will avert a default.

Wall Street firms — looking at tax revenues — are estimating that the day of reckoning is near. Goldman Sachs estimated that the “x-date” could be reached in June, at which point the “extraordinary” steps taken by the Treasury Department to keep the government running would be exhausted and bills would start going unpaid.

Both sides could tone down the rhetoric by committing first and foremost to the U.S. government avoiding a default on its payments, said Brian Riedl, a senior fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute. That could help to build credibility and show good faith in talks.