Heading into this year’s midterms, voting rights groups were concerned that restrictions in Republican-leaning states triggered by false claims surrounding the 2020 election might jeopardize access to the ballot box for many voters.

Those worries did not appear to come true. There have been no widespread reports of voters being turned away at the polls, and turnout, while down from the last midterm cycle four years ago, appeared robust in Georgia, a state with hotly competitive contests for governor and U.S. Senate.

The lack of broad disenfranchisement is not necessarily a sign that everyone who wanted to vote could; there is no good way to tell why certain voters did not cast a ballot.

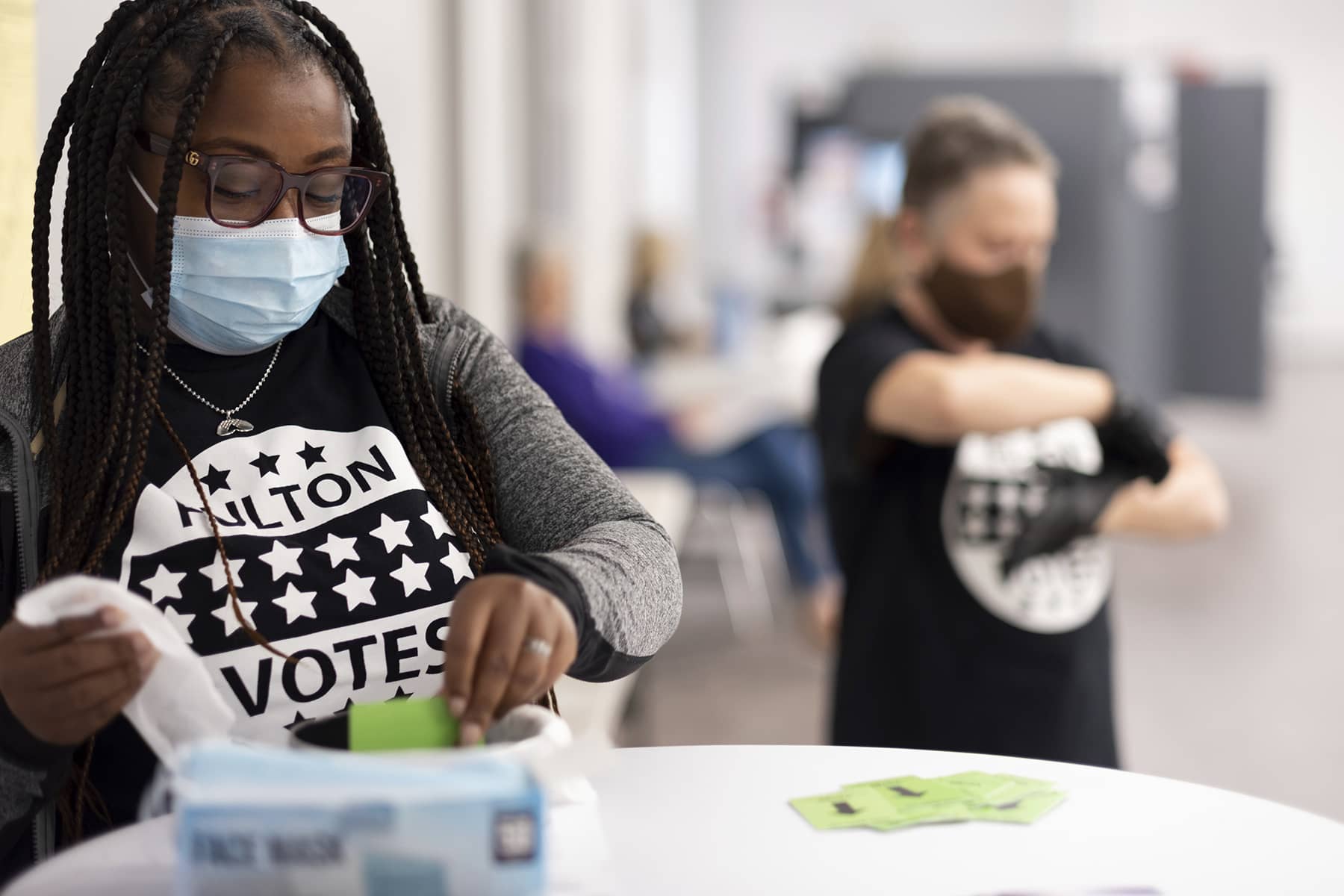

Voter advocacy groups promoted voter education campaigns and modified voting strategies as a way to reduce confusion and get as many voters to cast a ballot as possible.

“We in the voting rights community in Texas were fearing the worst,” said Anthony Gutierrez, director of Common Cause Texas. “For the most part, it didn’t happen.”

False claims that the 2020 election was stolen from former President Donald Trump undermined public confidence in elections and prompted Republican officials to pass new voting laws. The restrictions included tougher ID requirements for mail voting, shortening the period for applying for and returning a mailed ballot, and limiting early voting days and access to ballot drop boxes.

There is no evidence there was widespread fraud or other wrongdoing in the 2020 election.

An estimated 33 restrictive voting laws in 20 states were in effect for this year’s midterms, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. The most high-profile and sweeping laws were passed in Georgia, Florida, Iowa and Texas. Arizona also passed new voting rules, but those were largely put on hold this year or will take effect later.

Of the four states with major voting law changes in effect, a preliminary analysis shows a decline in turnout among registered voters in Florida, Iowa and Texas, while Georgia turnout declined slightly. Several factors can affect turnout, including voter enthusiasm and bad weather.

In Texas, the bumbling rollout of new voting restrictions in the state’s March primary resulted in officials throwing out nearly 23,000 mailed ballots as confused voters struggled to navigate new ID requirements.

But preliminary reports after the November 8 election showed rejection rates reverting to closer to more normal levels, which election officials attributed to outreach and mail voters figuring out the new rules. In San Antonio, county officials put the preliminary rejection rate at less than 2% — a sharp reversal from the 23% of mailed ballots they threw out in March.

Groups such as the Texas Civil Rights Project, working through churches and other organizations, focused on ensuring voters knew how to properly complete their mail ballots under the law known as Senate Bill 1.

“As a Texas community we’ve worked very hard to prepare for SB1,” said Emily Eby, the group’s senior election protection attorney.

Florida last year added a host of new rules around mail and early voting. They included new ID requirements, changes to how many ballots a person can turn in on behalf of someone else and limiting after-hours access to drop boxes. This year, lawmakers created a controversial new office dedicated to investigating fraud and other election crimes.

Still, voting appeared to be relatively smooth this year, before and on Election Day. Election officials reported no major problems.

Mark Earley, president of the Florida Supervisors of Elections, said the new laws did not greatly affect voter turnout or access this year, but said the rules, taken together, posed a challenge.

“When you put all of these together — the cumulative effect — it becomes confusing, difficult to communicate and educate the public about, difficult for the public to understand,” said Earley, who oversees elections in Tallahassee’s Leon County. “It becomes a big logistical and educational burden, and more hurdles for people to be able to jump over before they can get their ballots together.”

Iowa’s new law shortened the period for voters to return their mailed ballots, reduced polling place hours and early voting days, and prohibited anyone but close relatives, a household member or caregiver from dropping off someone else’s ballot.

More than 1.2 million voters cast ballots in the November 8 election. State officials said it was the second highest in state history for a midterm, but voting groups expressed concern that Latino participation may have declined due to the changes.

“We historically have had a fair amount of Latino voters who did the absentee ballot, which allowed LULAC volunteers to pick up those early ballots and return them to the county election offices,” said Joe Henry, a board member of the Iowa chapter of the League of United Latin American Citizens.

In Georgia, more votes were cast in this general election than in any prior midterm election — although with more voters on the rolls than four years ago, the actual turnout rate was lower.

Gabriel Sterling, interim deputy secretary of state, noted that most of the changes in the election law, known as Senate Bill 202, affected pre-Election Day voting — “and they blew away every record in that.”

He said more votes were cast early — both in person and by mail — than in any previous midterm election in the state. It was Election Day turnout that was lower than expected.

After Democrats won the 2020 presidential contest and two U.S. Senate runoff elections, the Republican-controlled Georgia Legislature passed a sweeping overhaul of the state’s election laws in 2021.

The law shortened the time period to request an absentee ballot and required voters to sign absentee ballot applications by hand, meaning they needed access to a printer. It also reduced the number of ballot drop boxes in the state’s most populous counties and limited the hours they were accessible.

Critics said the changes made it more difficult to cast mail ballots. Democrats urged people to vote early and in-person this year instead. Kendra Cotton, CEO of the New Georgia Project Action Fund, said she believes the election law did have a negative effect in a state where key races have been decided by narrow margins in recent elections.

“The narrative that’s out there is that SB202 was trying to depress the vote writ large, and we submit that that was not, in fact, the case,” she said. “It was trying to stop just enough people from voting that the electoral outcome here in Georgia would shift.”

This year, Republicans swept the statewide constitutional offices, and a Dec. 6 runoff will be held to decide the winner in the U.S. Senate race.

While she acknowledged there were not many problems on Election Day, Cotton said the law created a lot of “noise” that drained energy and resources from organizations such as hers.

“We’re having to go out and help voters fight to remain on the rolls,” Cotton said.

Voter advocacy groups already are mobilizing to support Georgia voters heading into the December 6 Senate runoff. Previously, runoffs were held nine weeks after an election. The new law shortened that to just four weeks, a period that also leaves too little time for new voter registrations.

“These types of tactics aim to suppress votes,” Andrea Hailey, CEO of Vote.org, said in a statement. “But Georgians have shown that they are ready and willing to navigate tough voting environments in order to make their voices heard.”