Widespread opposition to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine demonstrates the strength of a unified response against human rights abuses, and there are signs that power is shifting as people take to the streets to demonstrate their dissatisfaction in Iran, China and elsewhere, a leading rights group said in late January.

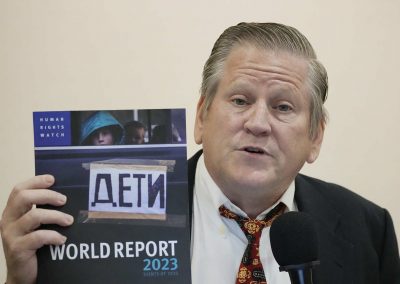

A “litany of human rights crises” emerged in 2022, but the year also presented new opportunities to strengthen protections against violations, Human Rights Watch said in its annual world report on human rights conditions in more than 100 countries and territories.

“After years of piecemeal and often half-hearted efforts on behalf of civilians under threat in places including Yemen, Afghanistan, and South Sudan, the world’s mobilization around Ukraine reminds us of the extraordinary potential when governments realize their human rights responsibilities on a global scale,” the group’s acting executive director, Tirana Hassan, said in the preface to the 712-page report.

“All governments should bring the same spirit of solidarity to the multitude of human rights crises around the globe, and not just when it suits their interests,” she said.

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a broad group of nations imposed wide-ranging sanctions while rallying to Kyiv’s support, while the United Nations Human Rights Council and the International Criminal Court both opened investigations into abuses, HRW said.

Countries now need to ask themselves what might have happened if they had taken such measures after Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, or applied the lessons elsewhere like Ethiopia, where two years of armed conflict has contributed to one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises, Hassan said.

“Governments and the U.N. have condemned the summary killings, widespread sexual violence and pillage, but have done little else,” she said of the situation in Ethiopia, where Tigray forces signed an agreement with the government late last year in hope of ending the conflict.

The New York-based organization highlighted the demonstrations in Iran that erupted in mid-September when Mahsa Amini died after being arrested by the country’s morality police for allegedly violating the Islamic Republic’s strict dress code, as well as protests in Sri Lanka that forced the government of President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to resign, and the democratic election in Brazil of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva over far-right Jair Bolsonaro.

“Courageous people time and again still take extraordinary risks to take to the streets, even in places like Afghanistan and China, to stand up for their rights,” HRW’s Asia director Elaine Pearson told reporters at the report’s launch in Jakarta.

In China, Human Rights Watch said the U.N. and others’ increased focus on the treatment of Uyghurs and Turkic Muslims in the Xinjiang region has “put Beijing on the defensive” internationally, while domestic protests against the government’s “zero-COVID” strategy also included broader criticism of President Xi Jinping’s rule.

As many Western governments turn away from China on trade toward India, however, Pearson admonished them not to ignore Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s own human rights record.

“India, under Prime Minister Modi, has also seen very similar abuses, the systematic discrimination against religious minorities, especially Muslims, the stifling of political dissent, the use of technology to suppress free expression and tighten its grip on power.”

At a later press conference in Beirut, HRW highlighted economic crises in the Middle East and North Africa that have impacted people’s ability to meet their basic needs and have, in turn, triggered social unrest and violence, sometimes followed by government repression.

“Outside of the Gulf, nearly every country in the region is suffering from some kind of major economic challenge,” said Adam Coogle, citing a growing currency crisis in Egypt and fuel and electricity crises in Lebanon and Syria. In Jordan, fuel price hikes have led to protests that turned violent.

One of the greatest humanitarian crises continues to be in Myanmar, where the military seized power in February 2021 from the elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi and since then has brutally cracked down on any dissent. The military leadership has taken more than 17,000 political prisoners since then and killed more than 2,700 people, according to the Assistance Association for Political Prisoners.

Human Rights Watch said peace attempts by Myanmar’s neighbors in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations have failed, and that aside from barring the country’s military leaders from its high-level meetings, the bloc has “imposed minimal pressure on Myanmar.”

It urged ASEAN to engage with opposition groups in exile and “intensify pressure on Myanmar by aligning with international efforts to cut off the junta’s foreign currency revenue and weapons purchases.”

In Jakarta, Pearson noted that the only lasting solution to the Rohingya refugee situation would be holding Myanmar’s government accountable for their persecution, and giving the Rohingya the ability to safely return.

“Most Rohingya want to go home, but they want safety, they want equal treatment, they want their land back, and they want the perpetrators of ethnic cleansing and acts of genocide held to account.”

HRW chose Indonesia, the current chair of ASEAN, as the site to launch its report in the hopes that Jakarta would use the opportunity to push the group to hold Myanmar to account for implementing its five-point peace process, Pearson said.

“We urge Indonesia to use the ASEAN chairmanship effectively to resolve the crisis in Myanmar,” she said. “The world’s response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine shows what is possible when governments work together.”

Domestically, Pearson said Indonesian President Joko Widodo’s admission to serious human rights violations at home in recent decades and vow to compensate victims was “significant,” but only as a first step.

“What we need now, going forward, is proper accountability for the victims of those abuses and the genuine commitment, going forward, to safeguarding human rights.”