With Labor Day comes big shopping sales and backyard barbecues. But the activist roots of the holiday are especially visible this year as unions challenge how workers are treated, from Hollywood to the auto production lines of Detroit.

The early-September tribute to workers has been an official holiday for almost 130 years — but an emboldened labor movement has created an environment closer to the era from which Labor Day was born. Like the late 1800s, workers are facing rapid economic transformation — and a growing gap in pay between themselves and new billionaire leaders of industry, mirroring the stark inequalities seen more than a century ago.

“There’s a lot of historical rhyming between the period of the origins of Labor Day and today,” Todd Vachon, an assistant professor in the Rutgers School of Management and Labor Relations, told The Associated Press. “Then, they had the Carnegies and the Rockefellers. Today, we have the Musks and the Bezoses. … It’s a similar period of transition and change and also of resistance — of working people wanting to have some kind of dignity.”

Between writers and actors on strike, contentious contract negotiations that led up to a new labor deal for 340,000 unionized UPS workers and active picket lines across multiple industries, the labor in Labor Day is again at the forefront of the holiday arguably more than it has been in recent memory. Here are some things to know about Labor Day this year.

WHEN WAS THE FIRST LABOR DAY OBSERVED?

The origins of Labor Day date back to the late 19th century, when activists first sought to establish a day that would pay tribute to workers.

The first U.S. Labor Day celebration took place in New York City on Sept. 5, 1882. Some 10,000 workers marched in a parade organized by the Central Labor Union and the Knights of Labor, according to the Labor Department and Encyclopaedia Britannica.

A handful of cities and states began to adopt laws recognizing Labor Day in the years that followed, yet it took more than a decade before President Grover Cleveland signed a congressional act in 1894 establishing the first Monday of September as a legal holiday.

Canada’s Labour Day became official that same year, more than two decades after trade unions were legalized in the country, according to Encyclopaedia Britannica.

The national holidays were established during a period of pivotal actions by organized labor. In the U.S., Vachon points to the Pullman Railroad Strike that began in May 1894, which effectively shut down rail traffic in much of the country.

“The federal government intervened to break the strike in a very violent way — that left more than a dozen workers dead,” Vachon says. Cleveland soon made Labor Day a national holiday in an attempt “to repair the trust of the workers.”

A broader push from organized labor had been in the works for some time. Workers demanded an 8-hour workday in 1886 during the deadly Haymarket Affair in Chicago, notes George Villanueva, an associate professor of communication and journalism at Texas A&M University. In commemoration of that clash, May Day was established as a larger international holiday, he said.

Part of the impetus in the U.S. to create a separate federal holiday was to shift attention away from May Day — which had been more closely linked with socialist and radical labor movements in other countries, Vachon said.

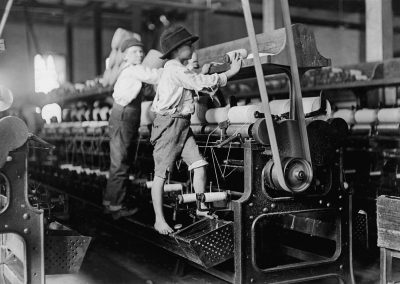

WAS CHILD LABOR A SIGNIFICANT PART OF THE AMERICAN LABOR STORY?

The United States was rapidly changing at the turn of the 20th century. Immigration and urbanization combined to create a massively stratified society, with the extremely wealthy living in opulence while the poorest city dwellers and immigrants lived in crowded and filthy tenements. To make ends meet in times of difficulty, many poor families had to rely on the work of all members, including the children.

It was not uncommon for children as young as four or five to work in places that were difficult and dangerous, and employers exploited children who had no other choice. While their conditions were not often acknowledged in their lifetimes, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 and its prohibition of employment of children in oppressive work remains part of their legacy.

HOW DID THE BAYVIEW TRAGEDY OF 1886 IN WISCONSIN INFLUENCE LABOR CONDITIONS?

Wisconsin’s most historic and bloody labor incident occurred on May 5, 1886 on the shores of Lake Michigan, in the Bay View area of Milwaukee. It began after four days of massive worker demonstrations throughout Milwaukee, in support of a law creating an eight-hour workday. Around 1,500 workers marched toward the Bay View Rolling Mills, then the area’s biggest manufacturer, urging the workers there to join the marches.

The State Militia lined up with guns ready on a hill at Superior Street and Russell Avenue. The marchers were ordered to stop about 200 yards away. When they did not, the militiamen fired into the crowd and killed seven people. The incident spurred workers and their families to build a more progressive society in Milwaukee and Wisconsin.

HOW HAS LABOR DAY EVOLVED OVER THE YEARS?

The meaning of Labor Day has changed a lot since that first parade in New York City. It hass become a long weekend for millions that come with big sales, end-of-summer celebrations and, of course, a last chance to dress in white fashionably. The origins of Labor Day remain faithful depending on where you live.

New York and Chicago, for example, hold parades for thousands of workers and their unions. Such festivities are not practiced as much in regions where unionization has historically been eroded, Vachon said, or didn’t take a stronghold in the first place.

When Labor Day became a federal holiday in 1894, unions in the U.S. were largely contested and courts would often rule strikes illegal, Vachon said, leading to violent disputes. It wasn’t until the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 that private sector employees were granted the right to join unions. Later into the 20th century, states also began passing legislation to allow unionization in the public sector — but even today, not all states allow collective bargaining for public workers.

Rates of organized labor have been on the decline nationally for decades. More than 35% of private sector workers had a union in 1953 compared with about 6% today. Political leanings in different regions has also played a big roll, with blue states tending to have higher unionization rates.

Nationwide, the number of both public and private sector workers belonging to unions actually grew by 273,000 thousand last year, the Bureau of Labor Statistics found. But the total workforce increased at an even faster rate — meaning the total percentage of those belonging to unions has fallen slightly.

WHAT LABOR ACTIONS ARE WE SEEING IN 2023?

Despite this percentage dip, a reinvigorated labor movement is back in the national spotlight. In Hollywood, screenwriters have been on strike for nearly four months — surpassing a 100-day work stoppage that ground many productions to a halt in 2007-2008. Actors joined the picket lines in July — as both unions seek better compensation and protections on the use of artificial intelligence.

Unionized workers at UPS threatened a mass walkout before approving a new contract last month that includes increased pay and safety protections for workers. A strike at UPS would have disrupted the supply chain nationwide.

Last month, auto workers also overwhelmingly voted to give union leaders the authority to call strikes against Detroit car companies if a contract agreement is not reached by the September 14 deadline. And flight attendants at American Airlines also voted to authorize a strike this week.

“I think there’s going to be definitely more attention given to labor this Labor Day than there may have been in many recent years,” Vachon said. Organizing around labor rights has “come back into the national attention. … And (workers) are standing up and fighting for it.”