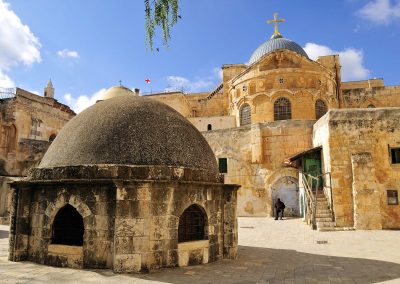

Christian worshippers thronged the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem on April 15 to celebrate the ceremony of the “Holy Fire,” an ancient ritual that sparked tensions this year with the Israeli police.

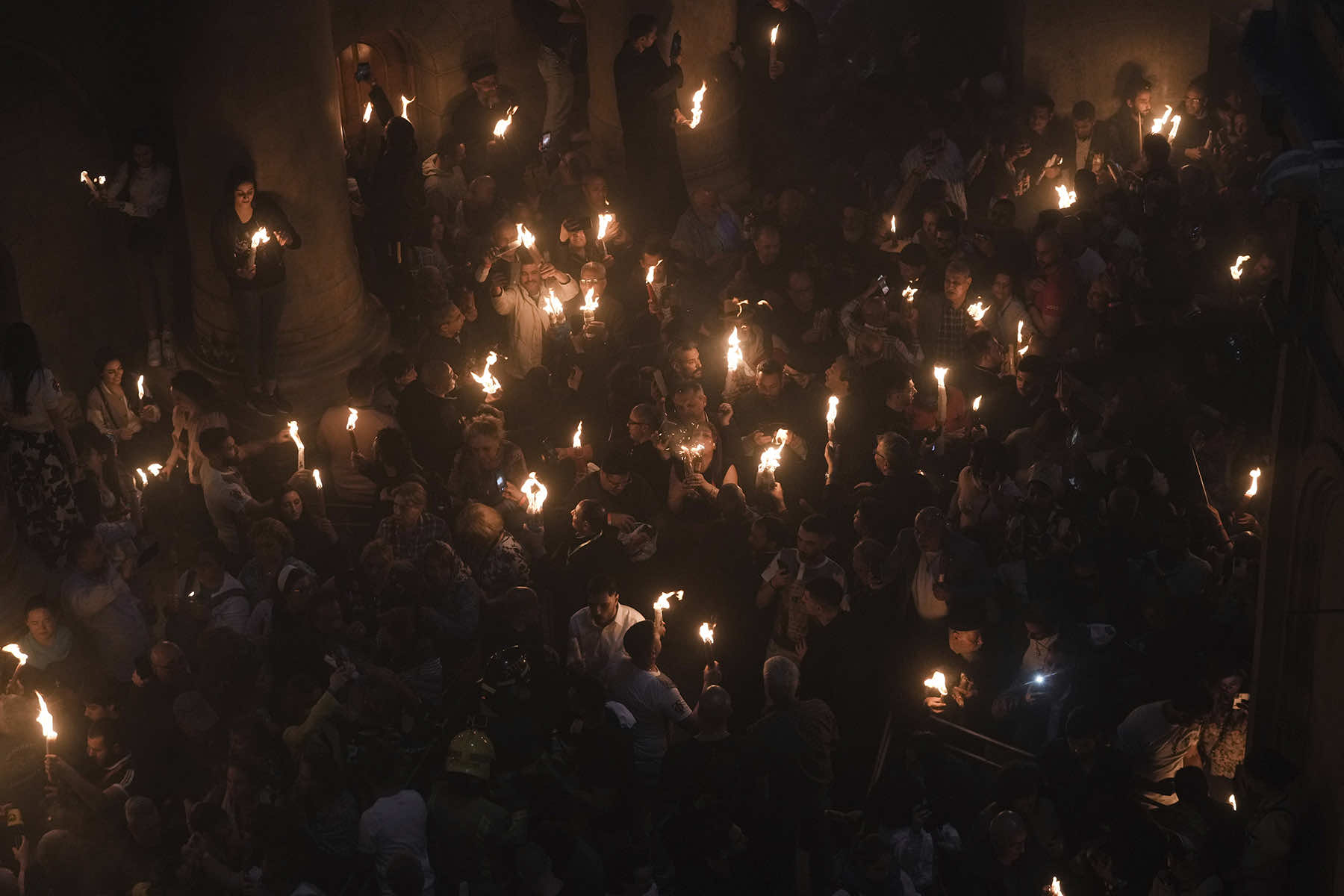

In the annual ceremony that has been observed for over a millennium, a flame taken from Jesus’ tomb is used to light the candles of fervent believers in Greek Orthodox communities near and far. The devout believe the origin of the flame is a miracle and is shrouded in mystery.

On April 15, after hours of frantic anticipation, a priest reached inside the dim tomb and ignited his candle. Each neighbor passed the light to another and, little by little, the darkened church was irradiated by tiny patches of light, which eventually illuminated the whole building.

Bells rang out. “Christ is risen!” the multilingual worshippers shouted. “He is risen indeed!”

Many trying to get to the church — built on the site where Christian tradition holds that Jesus was crucified, buried and resurrected — were thrilled to mark the rite of the Orthodox Easter week in Jerusalem. But for the second consecutive year, Israel’s strict limits on event capacity dimmed some of the exuberance.

“It is sad for me that I cannot get to the church, where my heart, my faith, wants me to be,” said 44-year-old Jelena Novakovic from Montenegro, who, like thousands of others, was trapped behind metal barricades that sealed off alleys leading to the Christian Quarter in Jerusalem’s walled Old City.

In some cases, the pushing and shoving escalated into violence. Footage showed Israeli police dragging and beating several worshippers, thrusting a Coptic Priest against the stone wall and tackling one woman to the ground. At least one older man was whisked, bleeding, into an ambulance.

Israel has capped the ritual to just 1,800 people. The Israeli police say they must be strict because they’re responsible for maintaining public safety. In 1834, a stampede at the event claimed hundreds of lives. Two years ago, a crush at a packed Jewish holy site in the country’s north killed 45 people. Authorities say they’re determined to prevent a repeat of the tragedy.

But Jerusalem’s minority Christians — mired in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and caught between Jews and Muslims — fear Israel is using the extra security measures to alter their status in the Old City, providing access to Jews while limiting the number of Christian worshippers.

The Greek Orthodox patriarchate has lambasted the restrictions as a hindrance of religious freedom and called on all worshippers to flood the church despite Israeli warnings.

As early as 8 a.m., Israeli police were turning back most worshippers from the gates of the Old City — including tourists who flew from Europe and Palestinian Christians who traveled from across the occupied West Bank — directing them to an overflow area with a livestream.

Angry pilgrims and clergy jostled to get through while police struggled to hold them back, allowing only a trickle of ticketed visitors and local residents inside. Over 2,000 police officers swarmed the stone ramparts.

Ana Dumitrel, a Romanian pilgrim surrounded by police outside the Old City, said she came to pay tribute to her late mother, whose experience witnessing the holy fire in 1987 long inspired her.

“I wanted to tell my family, my children, that I was here as my mom was,” she said, straining over the crowds to assess whether she had a chance.

After the ceremony, Palestinian Christians carried the fire through the streets and lit the tapers of the worshippers waiting outside. Chartered planes will ferry the flickering lanterns to Russia, Greece and beyond with great fanfare.

The dispute over the church capacity comes as Christians in the Holy Land — including the head of the Roman Catholic church in the region as well as local Palestinians and Armenians — say that Israel’s most right-wing government in history has empowered Jewish extremists who have escalated their vandalism of religious property and harassment of clergy. Israel says it’s committed to ensuring freedom of worship for Jews, Christians and Muslims.

Friction over the Orthodox Easter ritual has been fueled in part by a rare convergence of holidays in Jerusalem’s bustling Old City. A few hundred meters away from the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, Muslims fasting for the 24th day of the holy month of Ramadan were gathering for midday prayers at the Al-Aqsa mosque, the third-holiest site in Islam. Earlier this week, tens of thousands of Jews flocked to the Western Wall during the Passover holiday.

Tensions surged last week, when an Israeli police raid on the Al-Aqsa mosque compound, Jerusalem’s most sensitive site, ignited Muslim outrage around the world. The mosque is the third holiest site of Islam. It stands on a hilltop that is the holiest site for Jews, who revere it as the Temple Mount.

Israel captured the Old City, along with the rest of the city’s eastern half, in the 1967 Mideast war and later annexed it in a move not internationally recognized. Palestinians claim east Jerusalem as the capital of their hoped-for state.

In its limestone passageways on April 15, Christians pushed back by police were trying to cope with their disappointment. Cristina Maria, a 35-year-old who traveled from Romania to see the light kindled from the holy fire, said there was some consolation in the thought that the flame was symbolic, anyway.

“It’s the light of Christ,” she said, standing between an ice cream parlor and a dumpster in the Old City. “We can see it from here, there, anywhere.”