Storms, floods, fires and other extreme weather events led to more than 43 million displacements involving children between 2016 and 2021, according to a United Nations report.

More than 113 million displacements of children will occur in the next three decades, estimated the UNICEF report released on October 6, which took into account risks from flooding rivers, cyclonic winds and floods that follow a storm.

Some children, like 10-year-old Shukri Mohamed Ibrahim, are already on the move. Her family left their home in Somalia after dawn prayers on a Saturday morning five months ago.

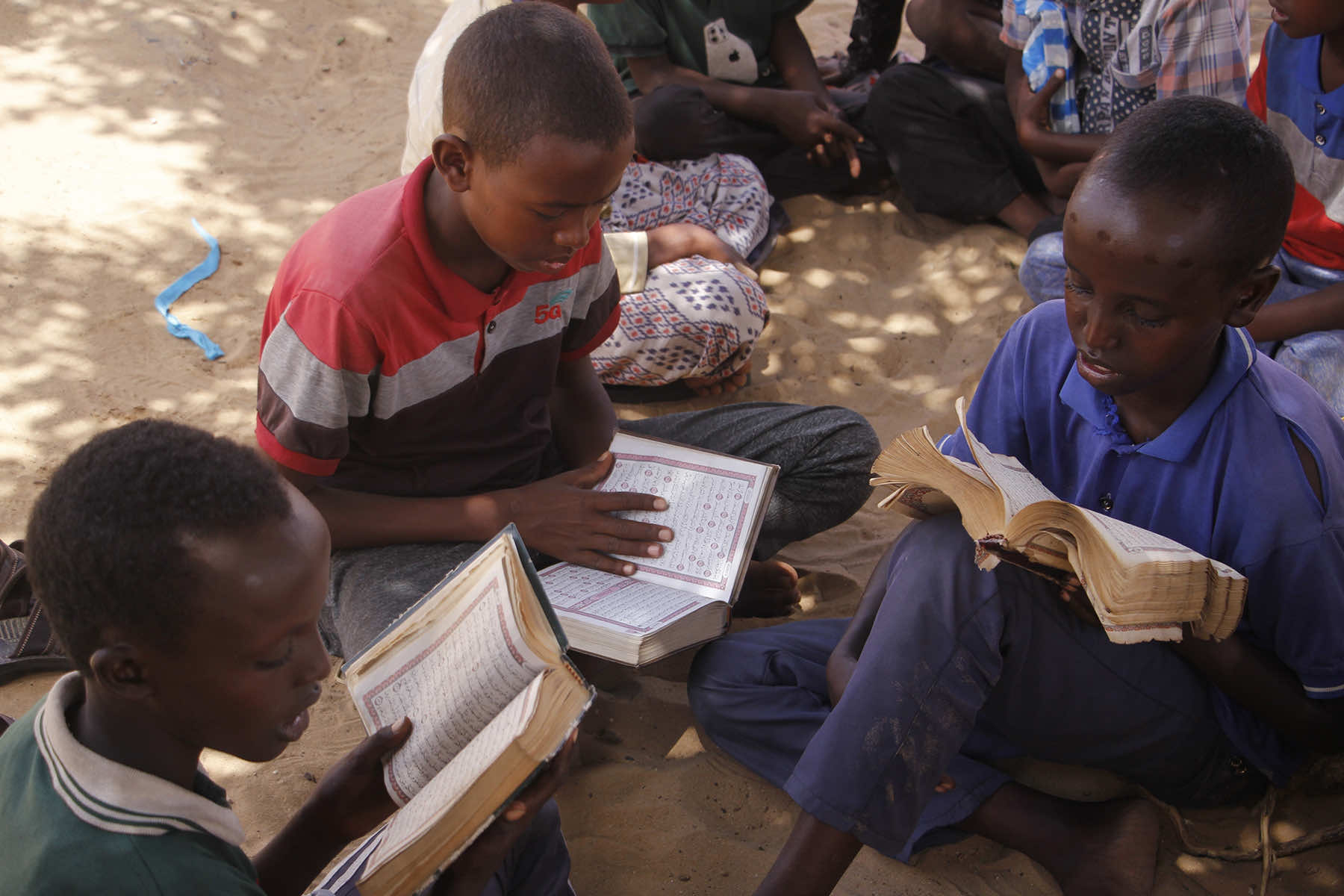

The worst drought in more than 50 years scorched the once-fertile pastures the family relied on, leaving them barren. So, bundling only a few clothes and some utensils into sacks, they moved to a camp in the capital Mogadishu, where Ibrahim, who dreams of being a doctor, is now going to school for the first time. That’s a plus, but the camp lacks proper shelter and sanitation, and food is scarce.

“We need something that can protect us from the heat during the day and the cold at night,” Ibrahim said.

The miseries of long, drawn-out disasters like droughts are often underreported. Children had to leave their homes at least 1.3 million times because of drought in the years covered by the report — more than half of them in Somalia — but this is likely an undercount, the report said. Unlike during floods or storms, there are no pre-emptive evacuations during a drought.

Worldwide, climate change has already left millions homeless. Rising seas are eating away at coastlines; storms are battering megacities and drought is exacerbating conflict. But while catastrophes intensify, the world has yet to recognize climate migrants and find formal ways of protecting them.

“The reality is that far more children are going to be impacted in (the) future, as the impacts of climate change continue to intensify,” said Laura Healy, a migration specialist at UNICEF and one of the report’s authors.

Nearly a third, or 43 million of the 134 million times that people were uprooted from their homes due to extreme weather from 2016-21 included children. Nearly half were forced from their homes by storms. Of those, nearly 4 of the 10 displacements were in the Philippines.

Floods displaced children more than 19 million times in places like India and China. Wildfires impacted children 810,000 times in the U.S. and Canada.

Data tracking migrations because of weather extremes typically don’t differentiate between children and adults. UNICEF worked with a Geneva-based nonprofit, the International Displacement Monitoring Center, to map where kids were most impacted.

The Philippines, India and China had the most child displacement by climate hazards, accounting for nearly half. Those countries also have vast populations and strong systems to evacuate people, which makes it easier for them to record data.

But, on average, children living in the Horn of Africa or on a small island in the Caribbean are more vulnerable. Many are enduring “overlapping crises” — where risks from climate extremes are compounded by conflict, fragile institutions and poverty, Healy said.

Leaving home subjects children to extra risks.

During unprecedented flooding of the Yamuna River in July in the Indian capital New Delhi, churning waters washed away the hut that was home to 10-year-old Garima Kumar’s family.

The waters also took her school uniform and her school books. Kumar lived with her family on sidewalks of the megacity and missed a month of school.

“Other students in the school teased me because my house had been flooded. Because we don’t have a permanent home,” Kumar said.

The floodwaters have receded and the family began repairing their home last month — a process Garima’s mother Meera Devi said they are having to do over and over again as floods are becoming more common. Her father, Shiv Kumar, hasn’t had any work for over a month. The family’s only income is the mother’s $2 daily earnings as a domestic helper.

Children are more vulnerable because they are dependent on adults. This puts them at the risk of being exploited and not having protections, said Mimi Vu, a Vietnam-based expert on human trafficking and migration issues who wasn’t involved with the report.

“When you’re desperate, you do things that you normally wouldn’t do. And unfortunately, children often bear the brunt of that because they are the most vulnerable and they don’t have the ability to stand up for themselves,” she said.

Vietnam, along with countries like India and Bangladesh, will likely have many children uprooted from their homes in the future, and policymakers and the private sector need to ensure that climate and energy planning takes into account risks to children from extreme weather, the UNICEF report said.

In estimating future risks, the report did not include wildfires and drought, or potential mitigation measures. It said vital services like education and health care need to become “shock-responsive, portable and inclusive,” to help children and their families better cope with disasters. This would mean considering children’s needs at different stages, from ensuring they have opportunities to study, that they can stay with their families and that eventually they can find work.

“We have the tools. We have the knowledge. But we’re just not working fast enough,” Healy said.