Almost a quarter of people who were dropped from Medicaid during the post-pandemic eligibility reviews are still uninsured and high costs are preventing them from getting on another plan, a new survey from KFF showed.

At least 20 million lower-income Americans have lost their federal health insurance since the provision that kept states from disenrolling people during COVID-19 ended in March 2023, according to KFF’s unwinding tracker. That is more than the Biden administration’s initial projection of 15 million people.

States have through at least June — some longer — to finish eligibility reviews, so experts say the number is likely to grow. Medicaid enrollment nationally rose by nearly one-third during the pandemic, from 71 million people in February 2020 to 94 million in April 2023.

The number of disenrollments and people without health insurance could be much higher, said Joan Alker, executive director and co-founder of Georgetown University’s Center for Children and Families. That’s because the survey doesn’t take into account children, who have been one of the biggest groups affected by unwinding.

“The question is, ‘How long are they going to stay uninsured?'” she said. “The states who want to cover their citizens are going to have to do a lot of work to get them back.”

Half of people who were enrolled in Medicaid prior to unwinding said they heard little or nothing at all about the process, according to the KFF survey, which includes responses from 1,227 adults who were previously covered by Medicaid.

Fifty-six percent of the people who were dropped said in the survey that they put off needed medical care while trying to renew.

And health care costs of any kind can be a major burden for low-income Americans, said Sara Rosenbaum of George Washington University’s School of Public Health and Health Services.

“Suddenly, a visit that didn’t cost you anything (before) – let’s say it’s going to cost you $5. That $5 can be $500 for some folks,” she said.

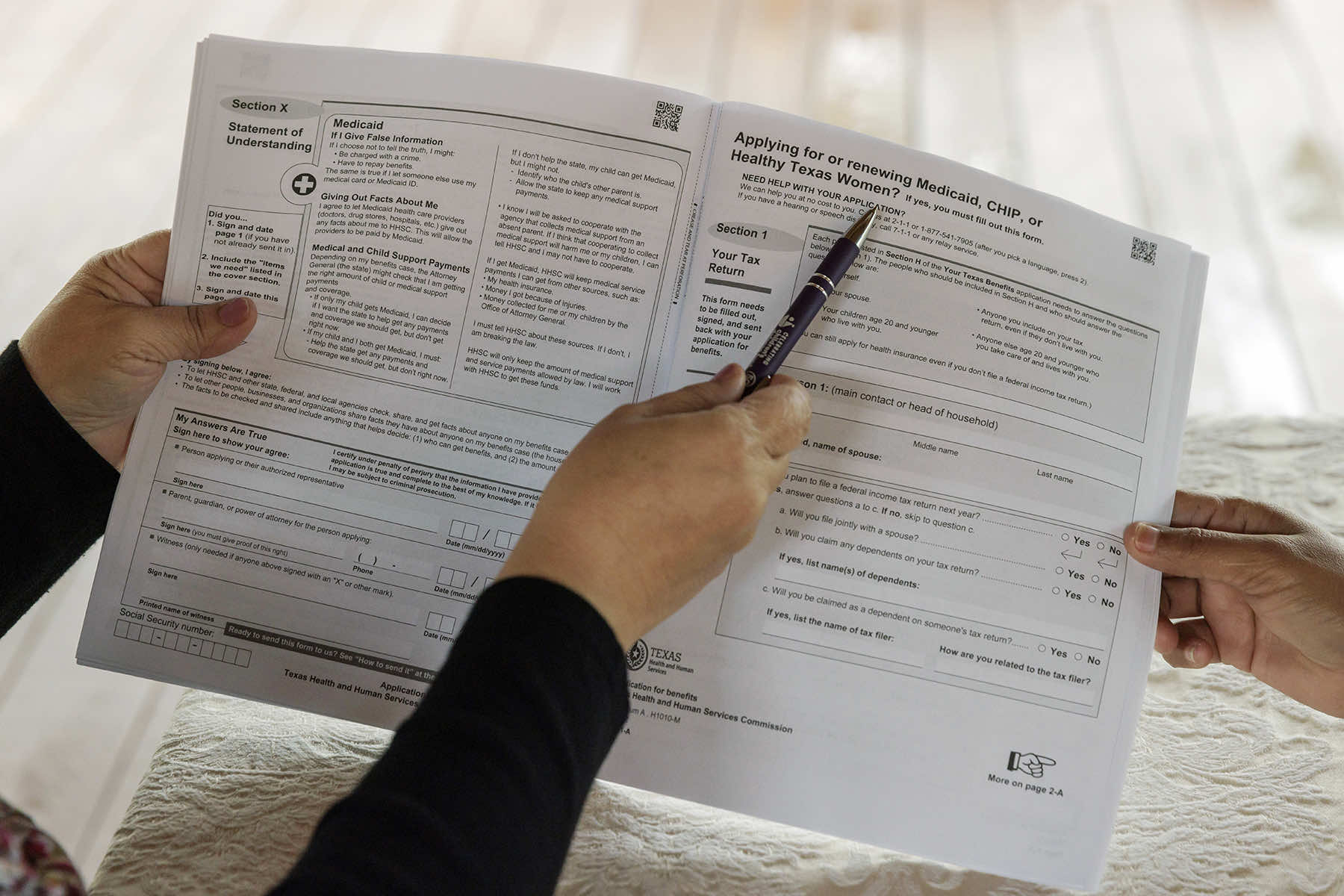

The majority of survey respondents also said they had problems when trying to renew their Medicaid coverage, like long wait times on the phone and issues with their paperwork. It’s in line with concerns that advocates and officials had about the large number of procedural disenrollments – when people were dropped due to errors in paperwork or failing to return the forms.

In the 10 states that have not yet expanded Medicaid, people were more likely to be required to provide proof of residency to renew their coverage, the KFF survey showed, with Black and Hispanic people overall more likely to be asked for proof.

That makes an already-complicated process even more arduous.

“We have known for decades that the more burdensome you make the application and renewal process,” Rosenbaum said, “the greater likelihood that completely eligible people will not get the coverage they’re entitled to get.”

More than 30 million people are still awaiting Medicaid renewals, while 43.6 million have had their coverage renewed, according to KFF.