The site of a transient motel in Detroit where three young Black men were killed, allegedly by White police officers, during the city’s bloody 1967 race riot is receiving a historic marker.

A dedication ceremony was held in July at a park several miles north of downtown where the Algiers Motel once stood.

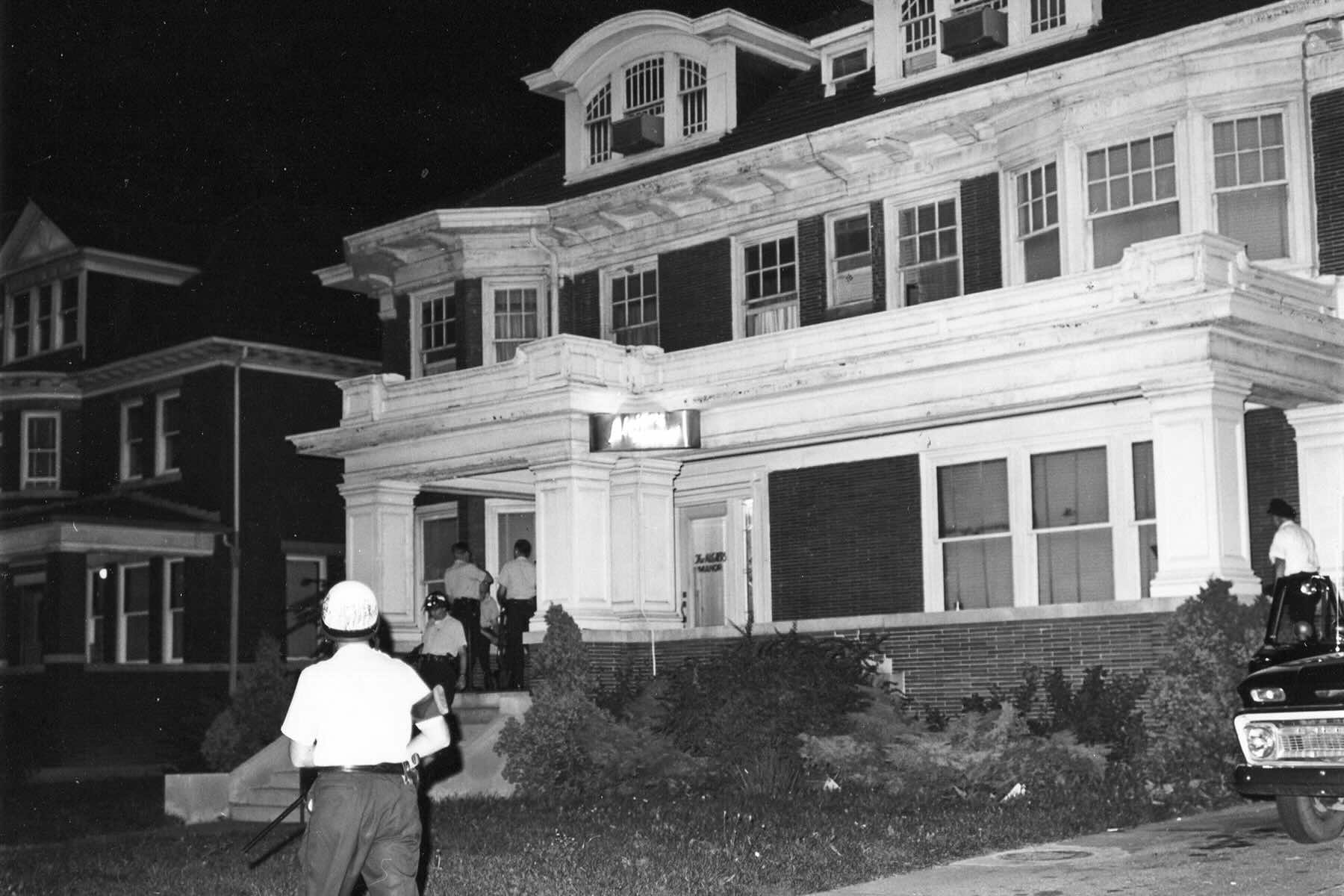

As parts of Detroit burned in one of the bloodiest race riots in U.S. history, police and members of the National Guard raided the motel and its adjacent Manor House on July 26, 1967, after reports of gunfire in the area.

The bodies of Auburey Pollard, 19, Carl Cooper, 17, and Fred Temple, 18, were found later. About a half dozen others, including two young White women, had been beaten.

The marker tells how the White officers were charged with murder following the deaths of Cooper, Temple and Pollard, but never convicted.

“A historical marker cannot tell the whole story of what happened at the Algiers Motel in 1967, nor adjudicate past horrors and injustices,” historian Danielle McGuire said. “It can, however, begin the process of repair for survivors, victims’ families, and community members through truth-telling.”

McGuire has spent years working with community members and the Michigan Historical Marker Commission to get a marker installed at the site.

“We have a moral duty to tell the truth about the past,” she said at the dedication. “A historical marker cannot change the past. It is no substitute for justice, but it can help us remember.”

Resentment among Detroit’s Blacks toward the city’s mostly-White police department had been simmering for years before the unrest. On July 23, 1967, it boiled over after a police raid on an illegal after-hours club about a dozen or so blocks from the Algiers.

Five days of violence would leave about three dozen Black people and 10 White people dead and more than 1,400 buildings burned. More than 7,000 people were arrested.

Lee Forsythe was one of the young men inside the Algiers’ Manor House when police raided it.

“I saw my best friend die,” Forsythe said of Cooper. “I heard him take his last breath.”

Forsythe said he was beaten about his head and needed stitches. He said the officers who beat him worked for the Detroit Police Department.

“They asked me what did I see, and put us on the wall,” he said. “And then they hit me on the back of the head, but then they told me ‘you better not fall.’ Fear can make you do a lot of things. Instead of falling, I dug my nails into a wall to keep myself from falling and dying. I was scared.”

The riot helped to hasten the flight of Whites from the city to the suburbs. Detroit had about 1.8 million people in the 1950s. It was the nation’s fourth-biggest city in terms of population in 1960. A half-century later, about 713,000 people lived in Detroit.

The plummeting population devastated Detroit’s tax base. Many businesses also fled the city, following the White and Black middle class to more affluent suburban communities to the north, east and west.

Deep in long-term debt and with annual multimillion-dollar budget deficits, the city fell under state financial control. A state-installed manager took Detroit into the largest municipal bankruptcy in U.S. history in 2013. Detroit exited bankruptcy at the end of 2014.

Today, the city’s population stands at about 633,000, according to the U.S. Census.

Mayor Mike Duggan called the marker’s dedication long overdue. Duggan said that while the city has a history of innovation “we also have a history of discrimination and racial injustice and tragedy.”

The Algiers, which was torn down in the late 1970s and is now a park, has been featured in documentaries about the Detroit riot. The 2017 film “Detroit” chronicled the 1967 riot and focused on the Algiers Motel incident.

“While we will acknowledge the history of the site, our main focus will be to honor and remember the victims and acknowledge the harms done to them,” McGuire said. “The past is unchangeable. But by telling the truth about history — even hard truths — we can help forge a future where this kind of violence is not repeated.”