Twenty more House Republicans, including House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, the top Republican in the House, signed onto the lawsuit filed by the Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton asking the Supreme Court first to take up the lawsuit, and then to throw out the presidential electors for Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Georgia, and Michigan on December 11.

If it would do so, those state legislatures could appoint a new slate of electors for Trump, thereby tossing out President-Elect Joe Biden’s victory in the 2020 election and handing the White House back to Trump.

And yet, on the evening of December 11, the Supreme Court refused to hear the case. Two justices, Justice Samuel Alito and Justice Clarence Thomas, said they would have permitted the court to hear the case—this is consistent with their longstanding position that the court must allow states to file in a dispute between states– but would have decided against it. So Trump, who had joined the Texas lawsuit, has lost his bid to have the Supreme Court overturn the election results.

The Electoral College meets on Monday, December 14, and Congress counts the electoral votes in a joint session on January 6. It is possible that Republican loyalists in the House will gum up the congressional acceptance of the electoral votes, but the election is over. Joe Biden will be inaugurated on January 20, 2021.

But the larger story is not over.

The Republican Party has become a dangerous faction trying to destroy American democracy. Fittingly, after the Supreme Court decision, the Chair of the Texas Republican Party, Allen West, promptly issued a grammatically muddy statement saying, “Perhaps law-abiding states should bond together and form a Union of states that will abide by the constitution.”

Americans unhappy with the results of a presidential election have done precisely this before. It was called “secession,” and it occurred in 1860 when elite southern Democrats tried to destroy the United States of America rather than accept the election of Republican Abraham Lincoln to the White House.

In 1860, as today, there were two competing visions of America. In the South, members of a small wealthy class had come to believe that they should lead society, and that “democracy” meant only that voters got to choose which set of leaders ruled them. Society, they said, worked best when it was run by natural leaders, the wealthy, educated, well-connected men who made up the region’s planter class.

As South Carolina Senator James Henry Hammond explained in 1858, society was naturally made up of a great mass of workers, rather dull people, but happy and loyal, whom he called “mudsills” after the timbers driven into the ground to support elegant homes above. These mudsills needed the guidance of their betters to produce goods that would create capital. That capital would be wasted if it stayed among the mudsills; it needed to move upward, where better men would use it to move society forward.

Ordinary men should, Hammond explained, have no say over policies, because they would demand a greater share of the wealth they produced. No matter what regular folks might want from the government—roads, schools, and so on—the government could not deliver it because it could do nothing that was not specifically listed in the Constitution. And what the Constitution called for primarily, he said, was to protect and spread the system of human enslavement that made men like him rich.

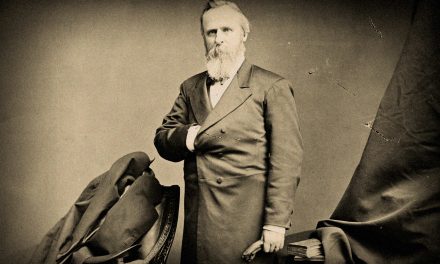

In 1859, Illinois lawyer Abraham Lincoln rejected Hammond’s vision of America. In a speech at the Milwaukee Agricultural Fair, Lincoln denied that there was any such thing as a “mudsill” in America. No one, he said, should be locked into working poverty for life. Society did not work best when a few rich men ran it, he said; it worked best when government made sure that everyone was equal before the law and that ordinary men had access to resources.

Under the system of “free labor,” hardworking farmers applied their muscle and brains to natural resources. They produced more than they could consume, and their accumulated capital employed shopkeepers and shoemakers and so on. Those small merchants, in turn, provided capital to employ industrialists and financiers, who then hired men just starting out. The economic cycle drove itself, and the “harmony of interest” meant that everyone could prosper in America so long as the government didn’t favor one sector over another.

Lincoln’s vision became the driving ideology of the Republican Party.

In 1860, when Democratic leaders demanded that the government protect the spread of slavery to the West, Republicans objected. They argued that the slave system, in which a few rich men dominated government and monopolized resources, would choke out free labor.

Southern Democratic leaders responded by telling voters the Republicans wanted a race war. To win the election, they silenced opponents and kept them from the polls. And when the Democrats nonetheless lost, southern leaders railroaded their states out of the Union and made war on the U.S. government. They threw away the idea of American democracy and tried to build a new nation they would control.

That moment looks much like the attempt of today’s Republicans to overturn a legitimate election and install their own leadership over the country.

But there the parallels stop. When southern Democratic leaders took their states out of the Union in 1861, they rushed them out before constituents could weigh in. Modern media means that voters have seen the ham-fisted legal challenges that have repeatedly lost in court, and have heard voices condemning this effort to overturn our democracy. Nebraska Senator Ben Sasse (R-NE), for example, issued a statement tonight: “Since Election Night, a lot of people have been confusing voters by spinning Kenyan Birther-type, ‘Chavez rigged the election from the grave’ conspiracy theories, but every American who cares about the rule of law should take comfort that the Supreme Court — including all three of President Trump’s picks — closed the book on the nonsense.”

Make no mistake, though: today’s Republican Party has drifted away from its original principles to attack American democracy. Fully 64% of the House Republican delegation endorsed Trump’s bid to steal the election. Some likely signed onto Paxton’s frivolous lawsuit because they honestly believed in it. Many others likely supported it either because they feared retaliation from Trump or they recognized that they would face primary challengers from the right in their gerrymandered districts in 2022 if they did not. Either way, the party as it currently exists is not going to repudiate this latest anti-American stand.

But Republicans who still value democracy and their traditional values of equality before the law and equal access to resources could repudiate the radicals who have taken over their party.

They could reject the ideology of the Confederacy and reclaim the Party of Lincoln.

Аl Drаgо

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics