“NUTS!” That was the official answer Brigadier General Anthony C. McAuliffe delivered to the four German soldiers sent on December 22, 1944, to urge him to surrender the town of Bastogne in the Belgian Ardennes.

In June 1944, on D-Day, the Allies had begun an invasion of northern Europe, and Allied soldiers had advanced against the German troops more quickly than anticipated. By December the Allied troops were stretched out along a 600-mile front and were tired.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower and his staff decided to hold the most fatigued troops in the easily defended Ardennes region over Christmas to let them rest. To reinforce them, they sent inexperienced troops. The Allies anticipated little trouble.

So they were surprised on December 16, 1944, when the Germans launched more than 400,000 personnel, more than 1,400 tanks and armored vehicles, 2,600 pieces of artillery, and more than 1,000 combat aircraft directly at a 75-mile stretch of the front in the Ardennes in an offensive designed to punch through the Allied lines.

And thus began the Battle of the Bulge.

This German counteroffensive moved forward fast, creating the bulge that gave the battle its name. But the German advance hit bottlenecks at Bastogne and other places, while isolated soldiers defended important crossroads and burned gasoline stocks to keep them out of German tanks. On December 22, 1944, as Allied troops were reeling, German soldiers brought to McAuliffe a demand that he surrender Bastogne.

“The fortune of war is changing,” their missive read. “This time the U.S.A. forces in and near Bastogne have been encircled by strong German armored units…. There is only one possibility to save the encircled U.S.A. troops from total annihilation: that is the honorable surrender of the encircled town…. If this proposal should be rejected one German Artillery Corps and six heavy A. A. Battalions are ready to annihilate the U.S.A. troops in and near Bastogne.”

It was that request that prompted McAuliffe’s “NUTS!” Members of his staff were more colorful when they had to explain to their German counterparts what McAuliffe’s slang meant. “Tell them to take a flying sh*t,” one said. Another explained: “You can go to hell.”

By the time of this exchange, British forces had already swung around to stop the Germans, Eisenhower had rushed reinforcements to the region, and the Allies were counterattacking. On December 26, General George S. Patton’s Third Army relieved Bastogne.

The Allied counter offensive forced back the bulge the Germans had pushed into the Allied lines. By January 25, 1945, the Allies had restored the front to where it had been before the attack and the battle was over.

The Battle of the Bulge was the deadliest battle for U.S. forces in World War II. More than 700,000 soldiers fought for the Allies during the 41-day battle. The U.S. alone suffered some 75,000 casualties that took the lives of 19,000 men. The Germans lost 80,000 to 100,000 soldiers, too many for them ever to recover.

The Allied soldiers fighting in that bitter cold winter were fighting against fascism, a system of government that rejected the equality that defined democracy, instead maintaining that some men were better than others. German fascists under leader Adolf Hitler had taken that ideology to its logical end, insisting that an elite few must lead, taking a nation forward by directing the actions of the rest.

They organized the people as if they were at war, ruthlessly suppressing all opposition and directing the economy so that business and politicians worked together to consolidate their power. Logically, that select group of leaders would elevate a single man, who would become an all-powerful dictator. To weld their followers into an efficient machine, fascists demonized opponents into an “other” that their followers could hate, dividing their population so they could control it.

In contrast to that system was democracy, based on the idea that all people should be treated equally before the law and should have a say in their government. That philosophy maintained that the government should work for ordinary people, rather than an elite few.

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt inspired the American people to defend their democracy — however imperfectly they had constructed it in the years before the war — and when World War II was over, Americans and their allies tried to create a world that would forever secure democracy over fascism.

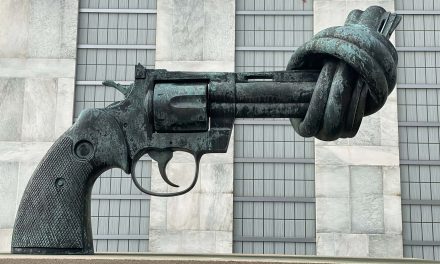

The 47 allied nations who had joined together to fight fascism came together in 1945, along with other nations, to create the United Nations to enable countries to solve their differences without war.

In 1949 the United States, along with Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, and the U.K., created the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), a peacetime military alliance to stand firm against aggression, deterring it by declaring that an attack on one would be considered an attack on all.

At home, the government invested in ordinary Americans. In 1944, Congress passed the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, more commonly known as the G.I. Bill, to fund higher education for some 7.8 million former military personnel. The law added to the American workforce some 450,000 engineers, 180,000 medical professionals, 360,000 teachers, 150,000 scientists, 243,000 accountants, 107,000 lawyers, and 36,000 clergymen.

In 1946 the Communicable Disease Center opened its doors as part of an initiative to stop the spread of malaria across the American South. Three years later, it had accomplished that goal and turned to others, combatting rabies and polio and, by 1960, influenza and tuberculosis, as well as smallpox, measles, and rubella.

In the 1970s it was renamed the Center for Disease Control and took on the dangers of smoking and lead poisoning, and in the 1980s it became the Centers for Disease Control and took on AIDS and Lyme disease. In 1992, Congress added the words “and Prevention” to the organization’s title to show its inclusion of chronic diseases, workplace hazards, and so on.

Congress invested in the nation’s infrastructure with projects like the Interstate Highway System, funded by the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act, which fueled the economy not just by providing jobs and tying together the states, but also by creating a market for new cars and for motels, diners, and gas stations along the new roads.

Americans also worked to put the racial segregation that had inspired Hitler behind them, using the federal government to level the playing field between white Americans, Black Americans, and people of color.

As Chris Geidner wrote on January 23 in Law Dork, that impulse had gained traction in 1941, when labor and civil rights leader A. Philip Randolph told President Franklin Delano Roosevelt that Black Americans were not being hired at the factories working in defense industries. He urged Roosevelt to issue an executive order requiring that factories that received federal contracts must hire Black workers.

As Geidner recounted, a week later, Roosevelt signed Executive Order 8802, saying it was “the policy of the United States “to encourage full participation in the national defense program by all citizens of the United States, regardless of race, creed, color, or national origin, in the firm belief that the democratic way of life within the Nation can be defended successfully only with the help and support of all groups within its borders.“

After the war, President Harry Truman desegregated the armed forces in 1948, and as Black and Brown Americans claimed their right to be treated equally, Congress expanded recognition of those rights with the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Shortly after Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed Executive Order 11246, translating FDR’s 1941 measure into the needs of the peacetime country. “It is the policy of the Government of the United States to provide equal opportunity in Federal employment for all qualified persons, to prohibit discrimination in employment because of race, creed, color, or national origin, and to promote the full realization of equal employment opportunity through a positive, continuing program in each executive department and agency.”

This democratic government was popular, but as the memory of the dangers of fascism faded, opponents began to insist that such a government was leading the United States to communism. Tax cuts for the wealthy and corporations, along with the deregulation of business and cuts to the social safety net, began to concentrate wealth at the top of society. As wealth moved upward, lawmakers chipped away at the postwar government that defended democracy.

And now, since the inauguration of President Donald Trump on January 20, the dismantling of that system is happening all at once.

“The Guardian” reported on January 24 that incoming Secretary of State Marco Rubio has ordered a halt to almost all foreign aid, with the exception of military assistance to Israel and Egypt. “The Guardian” noted that this order is likely unlawful, since Congress sets the budget and in 1974 declared it illegal for the president to impound funds.

Still, a source foresaw the end of the global influence the U.S. has had since World War II, telling “The Guardian” that: “Freezing these international investments will lead our international partners to seek other funding partners — likely U.S. competitors and adversaries — to fill this hole and displace the United States’ influence the longer this unlawful impoundment continues.”

As Peter Baker of “The New York Times” noted, new president Donald Trump is trying to break NATO by demanding that members increase military spending to 5% of their nations’ economies, although the U.S. currently spends about 3% of its GDP on defense.

If we were to meet that requirement, Baker points out, the U.S. would have to increase its defense budget by $567 billion a year. Isabel van Brugen of Newsweek reports that an Italian news agency says that Trump intends to pull about 20,000 U.S. troops from Europe and wants Europe to pay to maintain the rest.

Trump has undertaken to dismantle the postwar democratic government at home, too. He has stopped the funding for repairing roads, bridges, airports, and ports that passed Congress in a bipartisan vote in 2022, as well as taken away funding for new solar manufacturing plants and other new systems to address climate change.

He has frozen all travel and communications at the Department of Health and Human Services, including the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. “We’ve never seen anything like this,” one researcher told Dan Diamond, Lena H. Sun, Carolyn Y. Johnson, and Mark Johnson of the Washington Post. “This is like a meteor just crashed into all of our cancer centers and research areas.”

And, of course, Trump has declared a war on diversity, equity, and inclusion programs. In his revoking of LBJ’s Executive Order 11246, itself based on FDR’s Executive Order 8802, he explicitly rejected the principles for which the Americans fought in World War II.

January 25, 2025, marks eighty years since the end of the Battle of the Bulge.

The Germans never did take Bastogne.

Virginia Mayo (AP) and U.S. Army (via AP)

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics