Florida rolled out a new law that prohibits many Chinese citizens from buying property in the state, especially near important infrastructure like airports, refineries, and military installations.

As reported in The New York Times on May 7 by Amy Qin and Patricia Mazzei, more than three dozen states either have enacted or are crafting laws to restrict the purchase of land, businesses, or housing by Chinese nationals, even if they have legal residence in the United States. The justification for the laws is that Chinese investment in the U.S. is a national security risk, although Chinese nationals own less than 400,000 acres in the United States.

It was an odd echo, for in May of 1882, President Chester A. Arthur signed into law the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned Chinese workers, but not scholars, businessmen, or diplomats, from immigrating to the United States for ten years. This was the first federal limitation of voluntary immigration to the United States, and it would be extended for more than 60 years.

Chinese migrants had first come to California Territory after the discovery of gold there in 1848. Those who joined the rush to “Gold Mountain” were escaping the devastation of the First Opium War of 1839–1842, hoping to make money in America and then return to China, from which they could not legally emigrate.

Expecting to go home again, they retained their languages, their culture, and their clothing. They tended to work the mines Americans had cleaned of their biggest deposits, focusing on meticulous reworking of the gravel, and they did better than native-born Americans thought they should.

With the sudden influx of miners to the region, Congress scrambled to turn California into a state. In 1850 a legislature charged with establishing the legal framework for the proposed state adopted the federal law enacted a half-century earlier, in 1802, that limited citizenship to “free White persons.”

The state legislature then went on to impose a foreign miner’s tax on Chinese and Mexican miners; then, in 1854, the state courts agreed that Chinese nationals could not testify in court against white Americans. In 1855 the legislature tried to stop Chinese immigration altogether by passing a $50 tax on shipmasters for each person ineligible for citizenship they brought to the state.

The creation of different legal systems for native-born Americans and immigrants in California mirrored the same distinctions in eastern states, prompting members of the new Republican Party like New York’s William Henry Seward and Abraham Lincoln of Illinois to worry that the principle of the Declaration of Independence that “all men are created equal” was being left behind.

During the Civil War, congressmen were dismayed that European nations were not inclined to support the United States over the Confederacy, and they began to insist the U.S. must turn away from Europe and toward Asia for a new future. In 1867, Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner suggested that increased trade with China would expand human freedom, but he was not blind to the commercial possibilities.

“All are looking to the Orient…China and Japan, those ancient realms of fabulous wealth,” he said. “To unite the east of Asia with the west of America is the aspiration of commerce….”

In 1868 the United States ratified a treaty with China—the Burlingame Treaty—designed to promote the exchange of people and trade between the two countries. It recognized the right of Chinese to immigrate to the United States “for purposes of curiosity, of trade, or as permanent residents.”

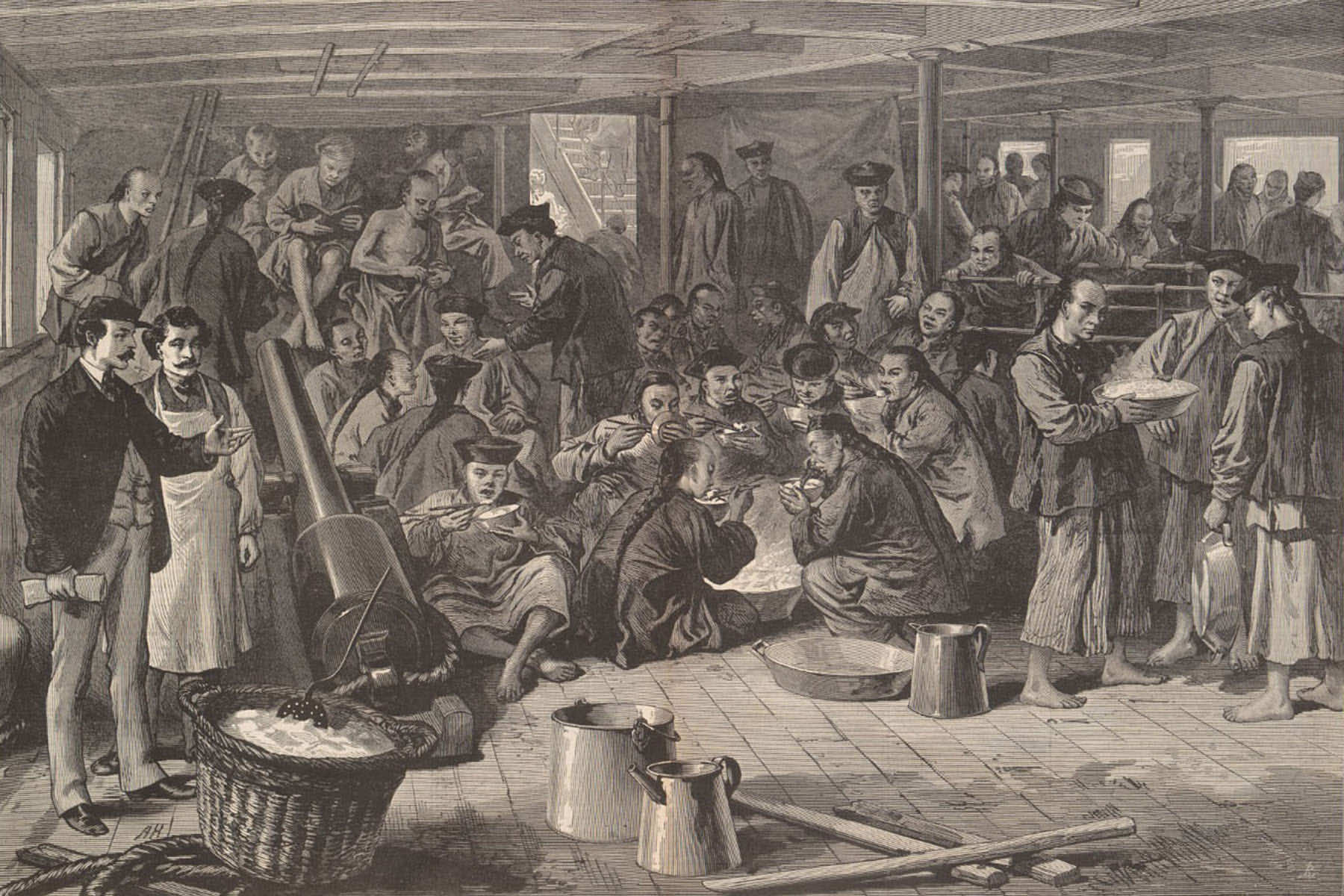

Trade between China and the United States picked up, with new ships, called “Down-Easters,” speeding across the waters of the Pacific to bring coal, oil, mechanical equipment, and consumer goods to China and bringing back Chinese sewing chests, shells, and fans that decorated upper-class homes, as well as passengers.

In 1869, in his annual message to Congress, President U. S. Grant noted that manufacturers were booming. “Through the agency of a more enlightened policy than that heretofore pursued toward China,” he said, “the world is about to commence largely increased relations with that populous and hitherto exclusive nation.”

That vision of global prosperity spread across the East Coast, where shipping towns thrived as their workmen built the schooners that traveled the Pacific trade, but it did not reach to the West Coast.

The same year the Senate ratified the Burlingame Treaty, the addition of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution should have overridden state discrimination against Chinese immigrants.

But a loophole that confirmed as citizens “all persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof” allowed western legislatures to fall back on the 1802 naturalization laws that limited citizenship to free white persons. Legislators assumed Chinese immigrants were excluded from citizenship, and in 1870, Congress bowed to that interpretation when it passed a new naturalization law.

A recession that hit California in the wake of the completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 exacerbated white inhabitants’ rejection of their Chinese neighbors. Railroad workers moved back to West Coast cities just as the connection to the markets of the East tanked prices in places like San Francisco and threw men out of work.

At the same time, the Burlingame Treaty brought more Chinese immigrants to the same cities, convincing white men that they were losing their jobs to an influx of Chinese competitors.

In San Francisco, Irish-born drayman Denis Kearney had built a successful business moving goods around the city by wagon. But he could go only so far because the leading businessmen who ruled San Francisco controlled the freight-moving business, and they refused to fix the street’s potholes.

In 1877, Kearney began to organize workingmen, urging them to rise up. Initially, Kearney praised Chinese workers, but he quickly began to blame them for white workingmen’s economic problems. He began to demand that employers fire all their Chinese workers, using the slogan: “The Chinese must go.”

In 1879, Republican senator James G. Blaine, who had an instinctive sense of which way the political winds were blowing and a desperate hunger for the presidency, backed the idea of ending Chinese immigration. Fellow eastern Republicans lambasted him for giving up on democratic principles of human equality, but the 1880 presidential election shocked them into his camp.

Republican James Garfield won the election, but by only slightly more than 8,000 votes out of more than 9 million cast. Party leaders had to figure out how to win more states in 1884, and California was a good place to start. Garfield had lost there by only 144 votes out of 164,218 cast.

In 1882, Republicans bowed to western sentiments and passed the Chinese Exclusion Act. Harper’s Weekly lamented Republican willingness to prohibit “the voluntary immigration of free skilled laborers into the country, and…to renounce the claim that America welcomes every honest comer.” In the following years, western states passed laws prohibiting intermarriage of Chinese with whites and prohibiting “aliens” from owning property.

In 1885, Chinese immigrant Saum Song Bo wrote a letter for a missionary magazine explaining his outrage upon being asked to contribute money to the pedestal for the Statue of Liberty.

“[T]he word liberty makes me think of the fact that this country is the land of liberty for men of all nations except the Chinese,” he wrote. “I consider it as an insult to us Chinese to call on us to contribute toward building in this land a pedestal for a statue of Liberty. That statue represents Liberty holding a torch which lights the passage of those of all nations who come into this country. But are the Chinese allowed to come? As for the Chinese who are here, are they allowed to enjoy liberty as men of all other nationalities enjoy it? Are they allowed to go about everywhere free from the insults, abuse, assaults, wrongs and injuries from which men of other nationalities are free?”

It was not until 1943, in the midst of a war in which China and the U.S. were allies, that the U.S. Congress overturned the Chinese Exclusion Act to permit quotas of Chinese immigrants to come to the U.S.

Today, lawmakers justify laws against Chinese property ownership on the grounds of national security, and the Chinese government is indeed known to use espionage to weaken its geopolitical rivals. But The New York Times reporters Qin and Mazzei note that national security experts say “that the specific threat posed by Chinese people owning homes has not been clearly articulated.”

For his part, University of Florida professor Zhengfei Guan, a Chinese national with lawful permanent residency in Florida, is suing the state over another new Florida law, this one banning state universities from working with people from “a country of concern,” including China. The law has created “a culture of fear,” a faculty member told Siena Duncan of Politico, and, if he loses his lawsuit, Guan is thinking of leaving. “My thought is this is not a place for me anymore,” he said.

Harper’s Weekly

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics