I have thought a lot lately about Representative Lauren Boebert’s (R-CO) tweet on January 6, 2021, saying, “Today is 1776.”

It is clear that those sympathetic to stealing the 2020 election for Donald Trump over the will of the majority of Americans thought they were bearing witness to a new moment in our history. But what did they think they were seeing?

Of course, 1776 was the year the Founders signed the Declaration of Independence, a stunning rejection of the concept that some men are better than others and could claim the right to rule. The Founders declared it “self-evident, that all men are created equal” and that ordinary people have the right to consent to the government under which they live.

But that declaration was not a form of government. It was an explanation of why the colonies were justified in rebelling against the king. It was the brainchild of the Second Continental Congress, which had come together in Philadelphia in May 1775 after the Battles of Lexington and Concord sparked war with Great Britain.

At the same time they were declaring independence, the lawmakers of the Second Continental Congress created a committee to write the basis for a new government. The committee presented a final draft of the Articles of Confederation in November 1777. Written at a time when the colonists were rebelling against a king, the new government decentralized power and focused on the states, which were essentially independent republics. The national government had a single house of Congress, no judiciary, and no executive.

“Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom and independence, and every Power, Jurisdiction and right, which is not by this confederation expressly delegated to the United States,” it read. The organization of the new government was “a firm league of friendship” entered into by the states “for their common defense.”

With the weight of governance falling on the states, the confederation languished. It was not until 1781 that the last of the states got around to ratifying the articles, and in 1783, with the end of the Revolutionary War, the government began to unravel. The Congress could make recommendations to the states but had no power to enforce them. It could not force the states to raise tax money to redeem the nation’s debts, and few of them paid up. Lacking the power to enforce its agreements, the Congress could not negotiate effectively with foreign countries, either, and individual states began to jockey to get deals for themselves.

As early as 1786, it was clear that the government was too decentralized to create an enduring nation. Delegates from five states met in September of that year to revise the articles but decided the entire enterprise needed to be reorganized. So, in May 1787, delegates from the various states (except Rhode Island) met in Philadelphia to write the blueprint for a new government.

The Constitution established the modern United States of America. Rather than setting up a federation of states, it united the people directly, beginning: “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

It corrected the weakness of the previous government by creating a president with explicit powers, giving the government the power to negotiate with foreign powers and to tax (although it placed the power of initiating tax bills in the House of Representatives alone), and creating a judiciary.

Those still afraid of the power of the government pushed the Framers of the Constitution to amend the document immediately, giving us the Bill of Rights that prohibits the government from infringing on individuals’ rights to freedom of speech and religion, freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures, and so on. The catch-all Tenth Amendment stated that “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.”

That reservation of powers to the states created a crisis by the 1830s, when state leaders declared they would not be bound by laws passed in Congress. Indeed, they said, if voters in the states wanted to take Indigenous lands or enslave their Black neighbors, those policies were a legitimate expression of democracy. To defend their right to enslave Black Americans, southern leaders took their states out of the Union after the election of 1860.

In the wake of the Civil War, Americans gave the federal government the power to enforce the principle that all people are created equal. In 1868, they added to the Constitution the Fourteenth Amendment, which declared that “No state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” It gave the federal government — Congress — the power to enforce that amendment.

It seemed that the Fourteenth Amendment would finally bring the Declaration of Independence to life. Quickly, though, state legislatures began to discriminate against the minority populations in their borders — they had always discriminated against women — and the American people lost the will to enforce equality. By the early twentieth century, in certain states white men could rape and murder Black and Brown Americans with impunity, knowing that juries of men like themselves would never hold them accountable.

Then, after World War II, the Supreme Court began to use the due process and the equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to overrule discriminatory laws in the states. It ended racial segregation, permitted interracial marriage, gave people access to birth control, permitted reproductive choice, and so on, trying to enforce equality before the law.

But this federal protection of civil rights infuriated traditionalists and White Supremacists. They threw in their lot with businessmen who hated federal government regulation and taxation. Together, they declared that the federal government was becoming tyrannical, just like the government from which the Founders declared independence. Since the 1980s, the Republican Party has focused on hamstringing the federal government and sending power back to the states, where lawmakers will have little power to regulate business but can roll back civil rights.

That effort includes rewriting the Constitution itself. In San Diego, California, last December, attendees at a meeting of the American Legislative Exchange Council’s policy conference announced they would push a convention to amend the U.S. Constitution to limit the power and jurisdiction of the federal government, returning power to the states.

ALEC formed in 1973 to bring businessmen, the religious right, and lawmakers together behind legislation. So far, 15 Republican-dominated states have passed legislation proposed by ALEC to call such a convention. In another nine similar states, at least one house has passed such bills, and lawmakers have introduced such bills in 17 other states.

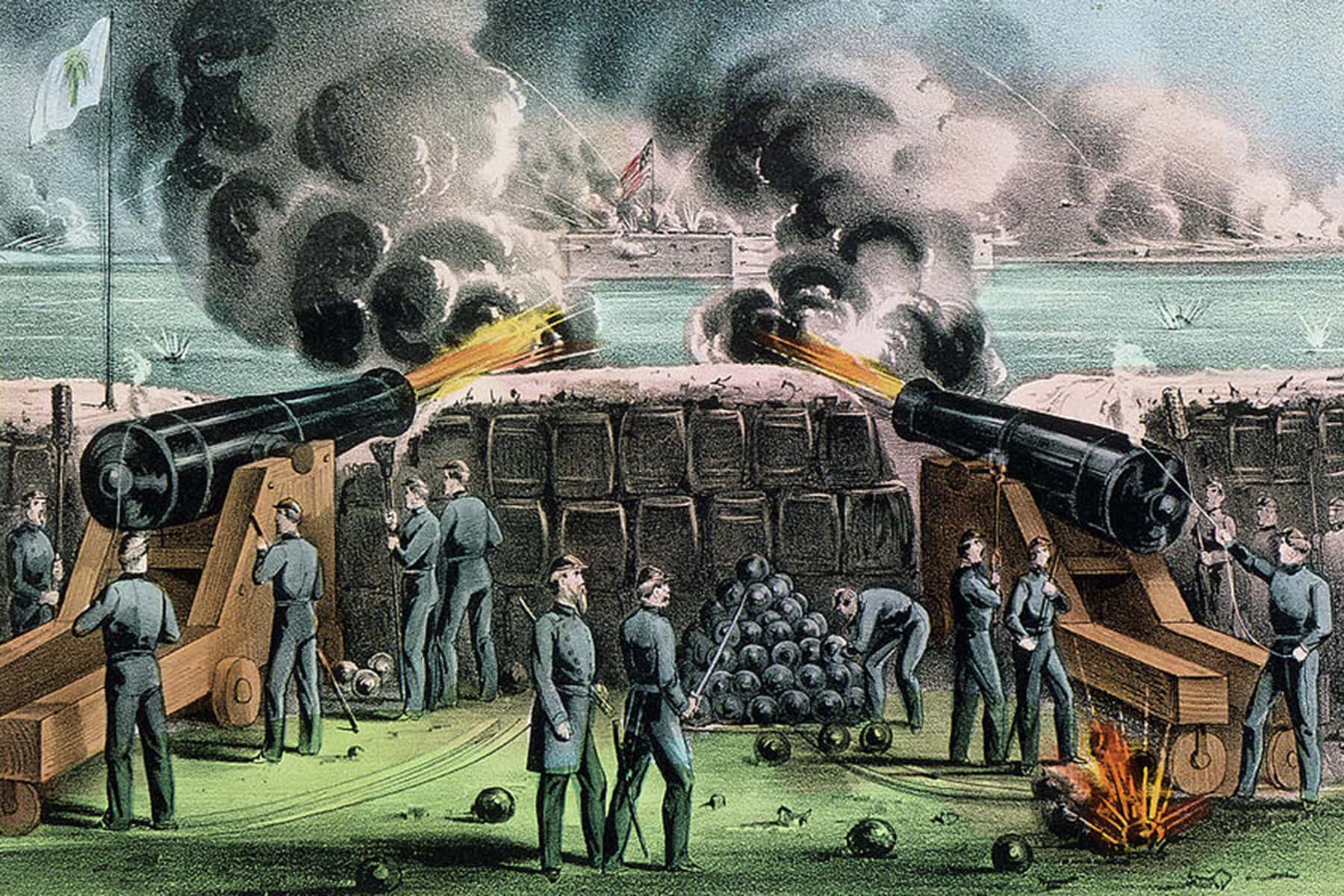

The insurrectionists’ cries of 1776 remind me not of the Founding era, but of 1860. In that time, too, people believed they were creating a new country and recorded their participation. In that time, too, the rebels wanted a country with a weak federal government, so they could be sure people like them would rule forever.

Currіеr & Іvеs / Library of Congress

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics