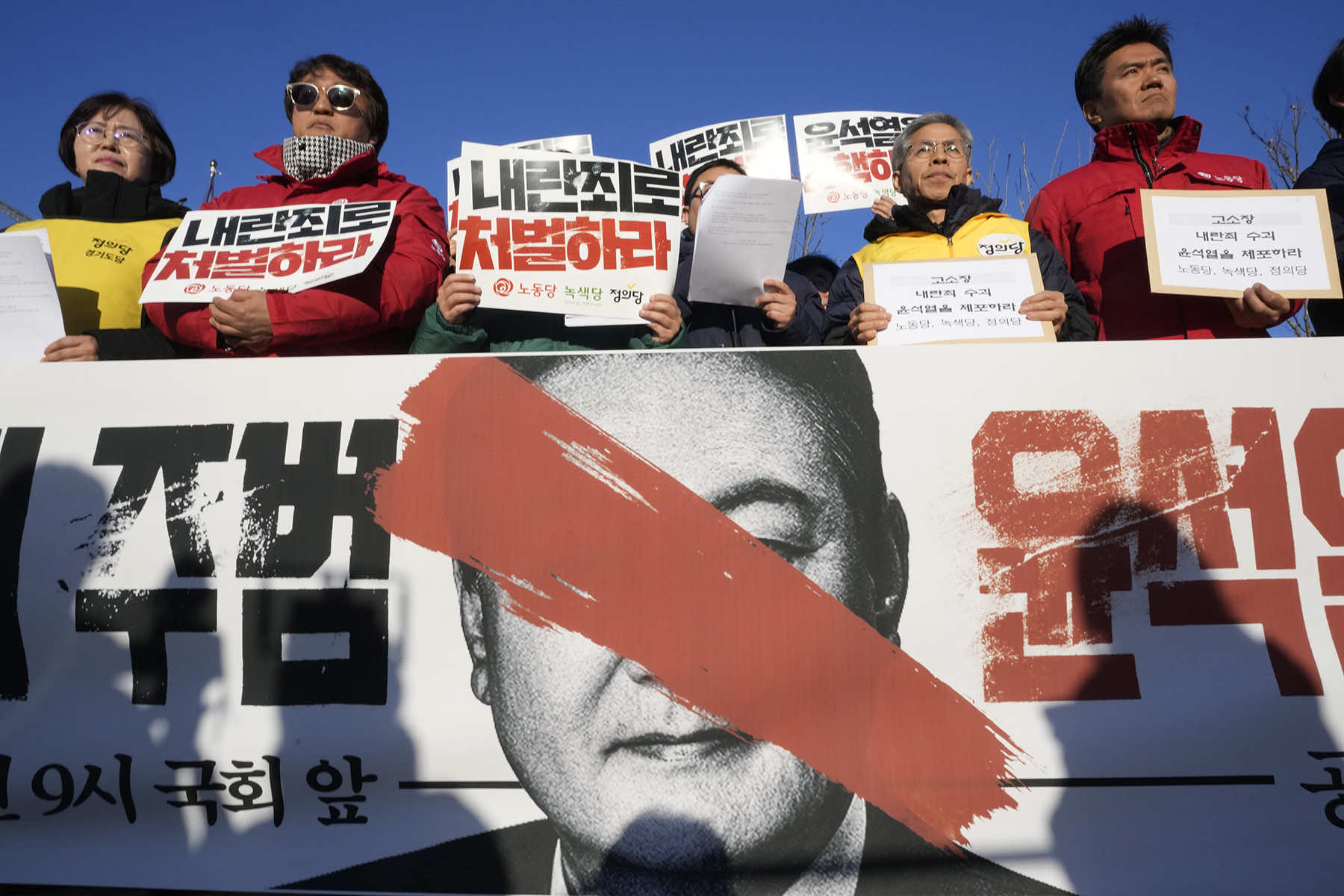

For an astonishing six hours today, South Korea underwent an attempted self-coup by its unpopular president, Yoon Suk Yeol, only to see the South Korean people force him to back down as they reasserted the strength of their democracy.

In an emergency address at nearly 11:00 last night local time, Yoon announced that he was declaring martial law in South Korea for the first time since 1980, when special forces under a military dictatorship attacked pro-democracy activists in the city of Gwangju, leaving about 200 people dead or missing. South Koreans ended military rule in their country in 1987, writing a new constitution that made South Korea a republic.

Yoon claimed he had to declare martial law because his political opponents were sympathizing with communist North Korea. It was a thin pretext.

A member of the conservative People’s Party, Yoon was elected to a five-year presidential term in 2022 after a misogynistic campaign fueled by young men who saw equal rights for women— whose average monthly wage is 67.7% of that a man, according to the BBC’s Laura Bicker—as reverse discrimination that is taking away their own rights and opportunities.

Before his election, Yoon had no experience in the National Assembly, and once he was in office, his popularity slid to record lows. In legislative elections held last April, voters crushed Yoon’s party, giving opposition parties 192 of 300 seats in the National Assembly. The legislature fought with Yoon over his budget and launched a number of corruption investigations into Yoon’s allies as well as his wife.

And so, Yoon declared martial law, bringing the media under his control and banning political activities, “false propaganda,” “gatherings that incite social unrest,” and strikes. Police officers formed a blockade around the National Assembly, and helicopters landed on the roof to prevent lawmakers from getting inside to overturn Yoon’s declaration.

The South Korean people reacted immediately. Reporting from Seoul, John Yoon of the New York Times recounted the story of a real estate agent who watched President Yoon’s speech, got in his car, and drove for an hour to get to the National Assembly. The man told journalist Yoon, “I thought, ‘The end has come,’ so I came out. The president of a country has exerted his power by force, and its people have come out to protest that. We have to remove him from power from this point on. He’s in a position where he has to come down.”

Editor of The Verge Sarah Jeong, who works out of the U.S. and does not cover South Korean politics, happened to be working in Seoul this week and was on site after a night of drinking, giving an informed and honest account of what she was seeing. “[T]he crowd is a pretty even mix of young people and the older folks (mostly men) who would have been young during the dictatorship…. I heard tanks were here but I haven’t seen one yet. [O]ld men swearing “how dare the military come here.”

Michelle Ye Hee Lee, Washington Post Tokyo/Seoul bureau chief, reported that the National Assembly managed to pull together a majority of its members—190 of 300—in about two and a half hours to participate in a unanimous vote to overturn Yoon’s emergency declaration of martial law. That vote included members of his own party.

Political commentator Adam Schwartz shared a video taken by the leader of South Korea’s Democratic Party, Lee Jae-myung, as he climbed over the wall of the National Assembly to vote against Yoon’s martial law declaration. Other videos showed people in the streets boosting legislators over the walls for the vote.

Yet another video showed South Korean soldiers trying to get into the National Assembly during the voting thwarted by people wielding a fire extinguisher and flashes from cameras.

While the law said Yoon had to abide by the legislators’ vote, it was not clear whether Yoon would do as the law required. About six hours after he had declared martial law, Yoon bowed to the National Assembly and the popular will and lifted his declaration.

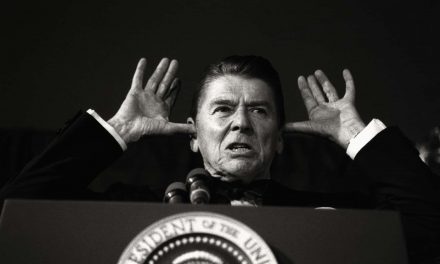

Yoon has been widely condemned, and South Koreans from all parties, including his own, are calling for his resignation or impeachment. Raphael Rashid of The Guardian reported today that on the morning after the attempted coup, South Koreans are bewildered and sad. “For the older generation who fought on the streets against military dictatorships, martial law equals dictatorship, not 21st century Korea. The younger generation is embarrassed that he has ruined their country’s reputation. People are baffled.”

For the rest of the world, though, South Koreans’ immediate and aggressive response to a man trying to take away their democratic rights is an inspiration. Among other things, it illustrates that for all the claims that autocracy can react to events more quickly than democracy can, in fact autocrats are brittle. It is democracy that is determined and resilient.

The events in Seoul also cemented the shift in social media from X to Bluesky, where news was breaking faster than anywhere else, in a way that echoed what Twitter used to be. Since Twitter was a key site of democratic organizing until Elon Musk bought it and renamed it X, that shift is significant.

And finally, the events in South Korea emphasize that for all people often look to larger-than-life figures to define our nations, our history is in fact made up of regular people doing the best they can. Journalist Sarah Jeong found herself entirely unexpectedly in the middle of a coup and, recognizing that she was in a historic moment, snapped to work to do all she could to keep the rest of us informed. “I’m f*cking blasted and hanging out in the weirdest scene because history happened at a deeply inconvenient hour,” she wrote on Bluesky. “[S]o it goes.”

When she finally went home, Jeong wrote: “I expensed my cab ride home. I’m tired so I put ‘korea coup’ down in the expense code field.”

Ahn Young-Joon (AP)

Letters from an Аmerican is a daily email newsletter written by Heather Cox Richardson, about the history behind today’s politics

- Exploring Korea: Stories from Milwaukee to the DMZ and across a divided peninsula

- A pawn of history: How the Great Power struggle to control Korea set the stage for its civil war

- Names for Korea: The evolution of English words used for its identity from Gojoseon to Daehan Minguk

- SeonJoo So Oh: Living her dream of creating a "folded paper" bridge between Milwaukee and Korean culture

- A Cultural Bridge: Why Milwaukee needs to invest in a Museum that celebrates Korean art and history

- Korean diplomat joins Milwaukee's Korean American community in celebration of 79th Liberation Day

- John T. Chisholm: Standing guard along the volatile Korean DMZ at the end of the Cold War

- Most Dangerous Game: The golf course where U.S. soldiers play surrounded by North Korean snipers

- Triumph and Tragedy: How the 1988 Seoul Olympics became a battleground for Cold War politics

- Dan Odya: The challenges of serving at the Korean Demilitarized Zone during the Vietnam War

- The Korean Demilitarized Zone: A border between peace and war that also cuts across hearts and history

- The Korean DMZ Conflict: A forgotten "Second Chapter" of America's "Forgotten War"

- Dick Cavalco: A life shaped by service but also silence for 65 years about the Korean War

- Overshadowed by conflict: Why the Korean War still struggles for recognition and remembrance

- Wisconsin's Korean War Memorial stands as a timeless tribute to a generation of "forgotten" veterans

- Glenn Dohrmann: The extraordinary journey from an orphaned farm boy to a highly decorated hero

- The fight for Hill 266: Glenn Dohrmann recalls one of the Korean War's most fierce battles

- Frozen in time: Rare photos from a side of the Korean War that most families in Milwaukee never saw

- Jessica Boling: The emotional journey from an American adoption to reclaiming her Korean identity

- A deportation story: When South Korea was forced to confront its adoption industry's history of abuse

- South Korea faces severe population decline amid growing burdens on marriage and parenthood

- Emma Daisy Gertel: Why finding comfort with the "in-between space" as a Korean adoptee is a superpower

- The Soul of Seoul: A photographic look at the dynamic streets and urban layers of a megacity

- The Creation of Hangul: A linguistic masterpiece designed by King Sejong to increase Korean literacy

- Rick Wood: Veteran Milwaukee photojournalist reflects on his rare trip to reclusive North Korea

- Dynastic Rule: Personality cult of Kim Jong Un expands as North Koreans wear his pins to show total loyalty

- South Korea formalizes nuclear deterrent strategy with U.S. as North Korea aims to boost atomic arsenal

- Tea with Jin: A rare conversation with a North Korean defector living a happier life in Seoul

- Journalism and Statecraft: Why it is complicated for foreign press to interview a North Korean defector

- Inside North Korea’s Isolation: A decade of images show rare views of life around Pyongyang

- Karyn Althoff Roelke: How Honor Flights remind Korean War veterans that they are not forgotten

- Letters from North Korea: How Milwaukee County Historical Society preserves stories from war veterans

- A Cold War Secret: Graves discovered of Russian pilots who flew MiG jets for North Korea during Korean War

- Heechang Kang: How a Korean American pastor balances tradition and integration at church

- Faith and Heritage: A Pew Research Center's perspective on Korean American Christians in Milwaukee

- Landmark legal verdict by South Korea's top court opens the door to some rights for same-sex couples

- Kenny Yoo: How the adversities of dyslexia and the war in Afghanistan fueled his success as a photojournalist

- Walking between two worlds: The complex dynamics of code-switching among Korean Americans

- A look back at Kamala Harris in South Korea as U.S. looks ahead to more provocations by North Korea

- Jason S. Yi: Feeling at peace with the duality of being both an American and a Korean in Milwaukee

- The Zainichi experience: Second season of “Pachinko” examines the hardships of ethnic Koreans in Japan

- Shadows of History: South Korea's lingering struggle for justice over "Comfort Women"

- Christopher Michael Doll: An unexpected life in South Korea and its cross-cultural intersections

- Korea in 1895: How UW-Milwaukee's AGSL protects the historic treasures of Kim Jeong-ho and George C. Foulk

- "Ink. Brush. Paper." Exhibit: Korean Sumukhwa art highlights women’s empowerment in Milwaukee

- Christopher Wing: The cultural bonds between Milwaukee and Changwon built by brewing beer

- Halloween Crowd Crush: A solemn remembrance of the Itaewon tragedy after two years of mourning

- Forgotten Victims: How panic and paranoia led to a massacre of refugees at the No Gun Ri Bridge

- Kyoung Ae Cho: How embracing Korean heritage and uniting cultures started with her own name

- Complexities of Identity: When being from North Korea does not mean being North Korean

- A fragile peace: Tensions simmer at DMZ as North Korean soldiers cross into the South multiple times

- Byung-Il Choi: A lifelong dedication to medicine began with the kindness of U.S. soldiers to a child of war

- Restoring Harmony: South Korea's long search to reclaim its identity from Japanese occupation

- Sado gold mine gains UNESCO status after Tokyo pledges to exhibit WWII trauma of Korean laborers

- The Heartbeat of K-Pop: How Tina Melk's passion for Korean music inspired a utopia for others to share

- K-pop Revolution: The Korean cultural phenomenon that captivated a growing audience in Milwaukee

- Artifacts from BTS and LE SSERAFIM featured at Grammy Museum exhibit put K-pop fashion in the spotlight

- Hyunjoo Han: The unconventional path from a Korean village to Milwaukee’s multicultural landscape

- The Battle of Restraint: How nuclear weapons almost redefined warfare on the Korean peninsula

- Rejection of peace: Why North Korea's increasing hostility to the South was inevitable

- WonWoo Chung: Navigating life, faith, and identity between cultures in Milwaukee and Seoul

- Korean Landmarks: A visual tour of heritage sites from the Silla and Joseon Dynasties

- South Korea’s Digital Nomad Visa offers a global gateway for Milwaukee’s young professionals

- Forgotten Gando: Why the autonomous Korean territory within China remains a footnote in history

- A game of maps: How China prepared to steal Korean history to prevent reunification

- From Taiwan to Korea: When Mao Zedong shifted China’s priority amid Soviet and American pressures

- Hoyoon Min: Putting his future on hold in Milwaukee to serve in his homeland's military

- A long journey home: Robert P. Raess laid to rest in Wisconsin after being MIA in Korean War for 70 years

- Existential threats: A cost of living in Seoul comes with being in range of North Korea's artillery

- Jinseon Kim: A Seoulite's creative adventure recording the city’s legacy and allure through art

- A subway journey: Exploring Euljiro in illustrations and by foot on Line 2 with artist Jinseon Kim

- Seoul Searching: Revisiting the first film to explore the experiences of Korean adoptees and diaspora