Steve Martin has long marveled at the many phases of his life. There was his youth as a Disneyland performer, surrounded by vaudeville performers and magicians. A decade as a stand-up before the sudden onset of stadium-sized popularity. An abrupt shift to movies. Later, a new chapter as a banjo player, a father and, a comedy act once again with Martin Short.

It is such a confounding string of chapters that Martin has typically only approached his life piecemeal or schizophrenically. He titled an audiobook “So Many Steves.” His memoir, “Born Standing Up,” covered only his stand-up years. In it, he wrote that it was really a biography “because I am writing about someone I used to know.”

“My life has many octopus arms,” Martin says, speaking from his New York apartment.

People participate in documentaries for all kinds of reasons. But Martin may be unique in making a film about his life with the instruction of: “See if you can make sense of all THAT.” Morgan Neville, the documentary filmmaker of the Fred Rogers film “Won’t You Be My Neighbor” and the posthumous Anthony Bourdain portrait “Roadrunner,” took up the challenge.

Yet Neville, too, was hesitant about any holistic view of Martin. The resulting film is really two. “STEVE! (martin) a documentary in 2 pieces,” premiered on Apple TV+ on March 29, splits Martin’s story in two halves.

One depicts Martin’s stand-up as it unfolded, with copious contributions from journal entries and old photographs. The other captures Martin’s life as it is today — riding electric bikes with Short, practicing the banjo — with reflections on the career that followed.

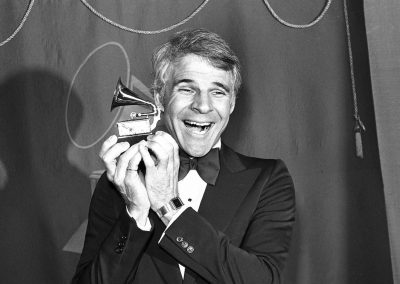

It is an attempt to synthesize all the Steve Martins, or at least line them up next to each other. The “King Tut” guy with the arrow through his head. The “wild and crazy guy.” The “Jerk.” The Grammy-winner. The novel writer. And the self-lacerating comic who says in the film: “I guarantee I had no talent. None.”

“I’m going to say something very immodest: I have a modesty about my career,” Martin says, chuckling. “Just because you do a lot of things doesn’t mean they’re good. I know that time evaluates things. So there’s nothing for me to stand on to evaluate my efforts. But an outsider can make sense of it.”

Neville, who joined the video call from his home in Pasadena, California, did not set out to make two films about Martin. But six months into the process, it crystalized for him as the right structure. Through lines emerged.

“When I look at the things Steve’s done in his life — playing banjo, magic, stand-up — these are things that take great effort to master,” Neville says. “But in a way, it’s the constant working at it. Even seeing Steve pick up a banjo, it’s never, ‘I nailed it.’ It’s always: ‘I could do that a little better.'”

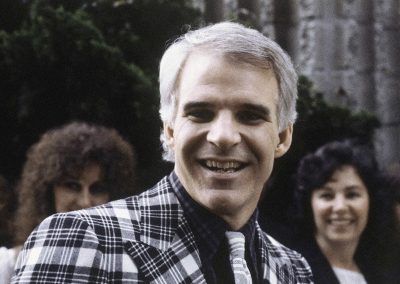

Looking back has not come naturally to Martin. He has long resisted the kind of life-story treatment of a film like “STEVE!” But Martin, 78, grants he is now at that time of life where you cannot help it. Even if reliving some things smarts.

“The first part, that’s what I really have a hard time watching,” Martin says. “When I’m on black-and-white homemade video being so not funny.”

Martin grew up in Orange County in awe of Jerry Lewis, Laurel and Hardy and Nichols and May. His first job, as an 11-year-old, was selling guide books at Disneyland. He drifted toward the Main Street Magic Shop. Stage performers like Wally Boag became his idols.

When Martin, after studying philosophy in college and writing for “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour,” began stand-up, he drew copiously from Boag and others, filtering the showmanship of vaudeville into an avantgarde act, just with balloon animals and an arrow through his head. Donning the persona of, as he says in the film, “a comedian who thinks he’s funny but isn’t,” his routine moved away from punchlines and toward an absurd irony with “free-form laughter.”

Martin’s act was groundbreaking and, in the 1970s, when most comics were doing political material, it became wildly popular. “He’s up there with the most idolized comedians ever,” Jerry Seinfeld says in the film. Now, Martin does not see much from those years that makes him laugh.

“Then there are these moments that I think of as performance glory, but they last a minute or two minutes. It was all so new. It was exciting because it was new to the audience and to me.”

Martin tends to be hard on himself. In one late scene in “STEVE!” he and Short are going over possible jokes, but most do not make the cut for Martin.

It is tempting to assign some of this nature to Martin’s famously critical father, Glenn, a real-estate salesman who had his own unrealized ambitions in show business. At dinner after the premiere of “The Jerk,” he pronounced his son “no Charlie Chaplin.” But Martin disagrees.

“I don’t think so,” says Martin. “It’s good to be hard on yourself. It’s just the way I do it. I just want to go over it and go over it. I realize it’s all in the details. It’s all in the timing.”

That makes Martin think of a joke that he and Short have considered for their act but thus far deemed too esoteric.

“I say, ‘You know, Marty, some comedians say funny things. And some comedians say things funny. And you just say … things,'” says Martin, laughing. “But there’s a truth in saying funny things and saying things funny. You walk the line. Our lives now are saying funny things and it used to be saying things funny.”

It is a line, typically exact in its wording, that perfectly represents the irony of Martin’s own life. In 1981, Martin quit stand-up, he thought for good. The act had run its course and he was happy to transition to movies. It was not until decades later, when Martin prepared to tour as a banjo player, that a friend convinced him audiences were going to want a little banter in between songs.

“So I had this terror and I started working on material,” Martin says. “Eventually I became what I grew up with, which is a folk music act with a funny monologist, making funny intros to songs.”

That has bled into Martin’s unexpected return to stand-up. Martin and Short, friends since the 1986 comedy “Three Amigos!” have become the premier double act of today, starring on the acclaimed Hulu series “Only Murders in the Building” and performing on the road. They cuttingly but affectionately volley quip after quip with the finesse of Grand Slam champions.

The irony is not lost on Martin. The no-punchline comedian has become a lover of punchlines.

“I’ve morphed into a person who really appreciates the joy of telling jokes,” shrugs Martin. “Marty and I in our show is joke after joke after joke.”

It is not the only reversal Martin never expected. After spending most of his life not wanting children, Martin and his wife of 17 years, Anne Stringfield, have an 11-year-old daughter. She is seen only as a cartoon in “STEVE!” to protect her privacy.

Even more confounding for Martin: After a life riddled by anxiety he is strangely content. Maybe even happy. “Yes, I hate to say it,” Martin says shaking his head.

Martin likes to say he has a “relaxed mind” now. He has peeled away a lot — competitiveness, people or situations who brought him grief — and has narrowed his life down to things that matter most to him.

“I have this thing that I’ve noticed,” Martin says. “As we age, we either become our best selves or our worst selves. I’ve seen people become their worst selves and I’ve seen people who were tough, difficult people early on become better selves.”

In the film, Martin puts it: “I look back and go, ‘What an odd life.’ My whole life was backwards.”