I have spent the better part of the last twenty years of my life immersed in learning American history at a level that few would ever have the time or desire to delve into. People ask me how I talk about the ugly parts of American history without breaking down emotionally. What they don’t know is that I do break down emotionally.

This journey, this path down the road of learning so that I can teach, is chock full of heartache. I love learning but I hate what I’ve learned. The story of America I was taught in school is not truthful. The story includes lies of omission. It lies on purpose to protect the facade of “freedom loving” America that has been sold to us all.

The stories I’ve read tell a different version of events. It does not make me proud of America. It does not make me want to say the Pledge of Allegiance, or to place my hand over my heart during the national anthem. The stories I’ve learned make me cry. It makes me cry for the families of the disregarded, dehumanized and disrespected. The stories make me cry for the memories of untold millions who suffered in America.

The stories are often very personal for me. There is one story in particular that stands out to me. It is the story of a woman named Mary Diltz. She was the second wife of a German immigrant who moved to this country to start a new life. His name was Dempsey Diltz. As was so common at the time in the antebellum south, he purchased African people to work for him for free. Most call this system slavery but it was not slavery. It was human bondage. Human beings were kidnapped, taken away from their homelands, bound in shackles, placed in dungeons waiting weeks or months to be sold on the coast of Africa.

Once sold to the crew of slaving ships bound for America, somehow, someway my family members survived the horrendous conditions onboard those filth ridden ships. They survived because they were strong. They survived despite the elements they were exposed to — rat and roach infested ships in chains like animals with temperatures well above one hundred degrees in the hold, with barely any victuals (you can’t honestly describe it as food), and barely any water to drink. Diseases killed many. Some probably jumped overboard from the untold numbers of ships that transported the people who were my ancestors.

At the end of the journey on the east coast of America, people like Dempsey Diltz awaited them. These people like Diltz knew full well they could buy these men, women and children and make a living keeping them in bondage. They knew that the state and federal governments sanctioned this practice. They knew that it was their meal ticket to the American dream.

When the government under President Andrew Jackson, rid the Mississippi Valley of Native Americans and gave the land to White men like Dempsey Diltz, “pioneers” made their way to some of the most fertile land on the planet. They did not come alone. They packed up all of their worldly possessions to start a new life.

This was a new life that they looked forward to. My ancestors did not look forward to this new life. There would be nothing new about it. It would be the continuation of generations of captivity in a strange land, disconnected from their family ties in Africa.

Every ten years since 1790 the United States has conducted a federal census. In 1850 and 1860 Dempsey Diltz and his family lived in Yalobusha County, Mississippi. The African people he’d purchased or otherwise acquired through the birth of children by those he enslaved would be counted as well. Those children began their lives in bondage. Not a moment of their early lives would they breathe air as a free person.

When the government census takers counted the Africans, their names were not recorded like those of Whites. They were accounted for on what were known as slave schedules. What an odd name for such a document. The age, gender and so-called racial classification was listed on these slave schedules but not the names of these human beings.

They were listed the same way livestock was accounted for, as just another commodity or piece of property known as chattel. It was not until after the Civil War — fought to determine if the slave states or the free states would dictate government policies moving forward — that all Blacks were listed by name on the census.

When the state of Mississippi joined ten other states in seceding and forming the Confederacy in 1861 they told the world why in a document they called A Declaration of the Immediate Causes which Induce and Justify the Secession of the State of Mississippi from the Federal Union.

“In the momentous step which our State has taken of dissolving its connection with the government of which we so long formed a part, it is but just that we should declare the prominent reasons which have induced our course. Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery– the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of commerce of the earth. These products are peculiar to the climate verging on the tropical regions, and by an imperious law of nature, none but the black race can bear exposure to the tropical sun. These products have become necessities of the world, and a blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization. That blow has been long aimed at the institution, and was at the point of reaching its consummation. There was no choice left us but submission to the mandates of abolition, or a dissolution of the Union, whose principles had been subverted to work out our ruin.”

Somewhere along the way Dempsey Diltz met and married a woman named Mary. She eventually died and he married a second woman, also named Mary. He preceded this second wife in death and left all of his worldly possessions to her.

In the early 1990s I began to trace my family tree on my mother’s side of the family. I found out about Dempsey Diltz and wanted to know more about this man. I left a message on a genealogical website chat inquiring about Dempsey Diltz. A woman contacted me shortly afterwards and told me that he was one of her ancestors. She and I communicated over the phone and through letters several times. She sent me his entire family tree, which I still posses. I learned about the journey to Mississippi that he took, while dragging my family members along. Dempsey Diltz died in Mississippi in 1862.

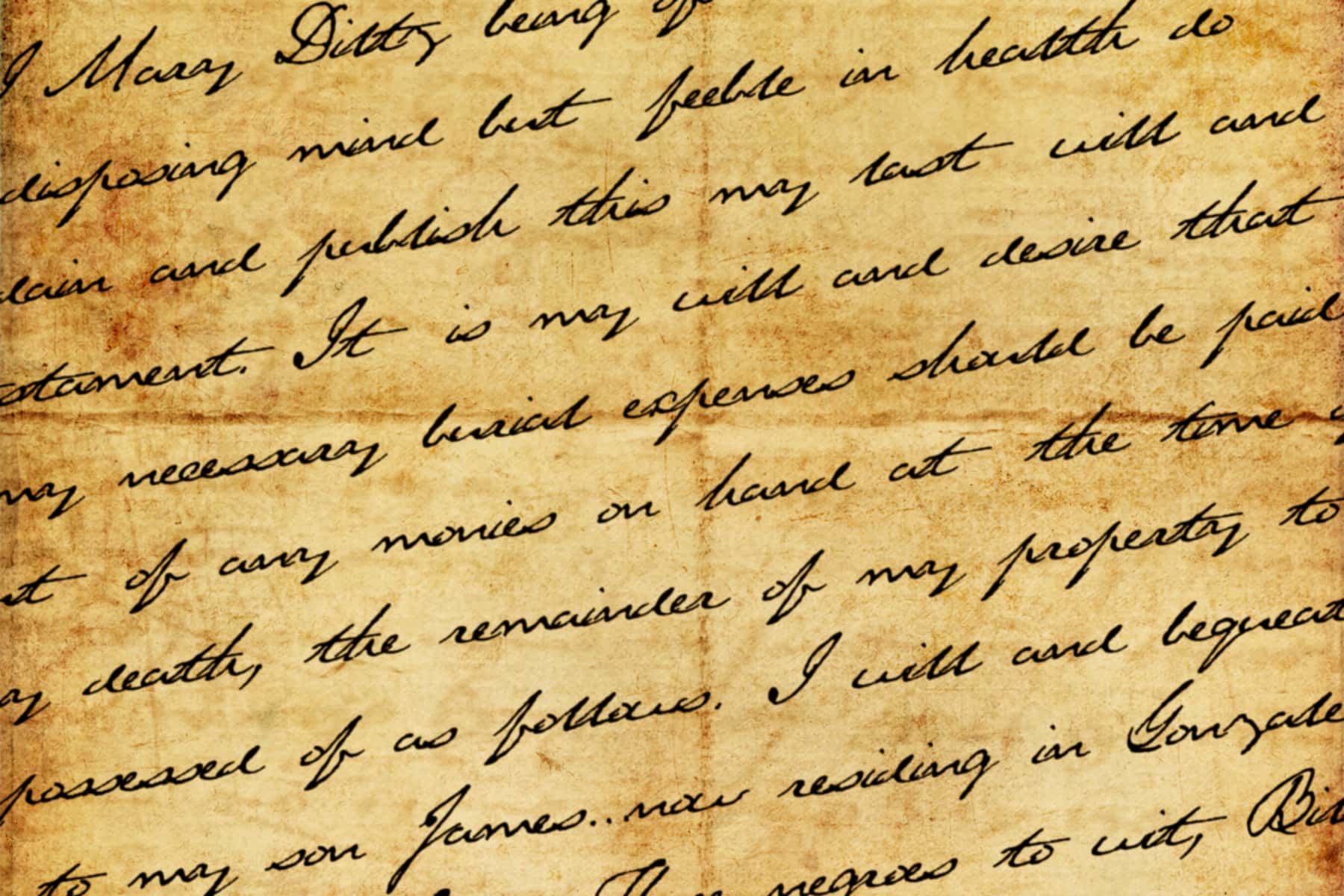

Eventually she sent me a document with the words of the last will and testament of the second Mary Diltz written before her 1864 death. This document and the words in it was one of those things I read that changed my world. This document ripped my heart out. It was written in 1863. I’ll share a little of what it said.

“I Mary Diltz being of sound mind and disposing mind but feeble in health do ordain and publish this my last will and testament. It is my will and desire that my necessary burial expenses should be paid out of any monies on hand at the time of my death, the remainder of my property to be possessed of as follows. I will and bequeath to my son James…now residing in Gonzalez County, Texas, Three negroes to wit, Bill John and Fillis also one axe mason one bed and bed clothing belonging to the same also the sum of Five Hundred dollars to be paid over by my executor herein after named upon the application…to be paid in Confederate money…I will and bequeath the following negroes to wit Messiah and her three children Emma Mitchell and Ada to be equally divided between my said daughter…and my said four grandchildren…one half of said negroes and the other half to be equally divided between my said grandchildren…and if said negroes cannot be satisfactorily divided as above provided for then it is my desire that they be sold by my executors and the proceeds of said sale divided as above said…”

Mary Diltz went on to bequeath the remainder of her worldly possession to her family as well. Although many of us in the Black community have had our family members given away in wills, few have ever seen the written words.

I was pretty young when I received this document and did not truly appreciate its’ importance. A system that most people casually refer to as slavery provided future wealth for the Diltz family by using my ancestors bodies to build generational wealth.

I have not investigated further to find out what eventually happened to those family members bequeathed to the Diltz family and sent to Texas. I might at some time in the future endeavor to follow their path. It is difficult to do, but might provide me a sense of connectedness to long lost family. Those family members who remained in Mississippi eventually led to my birth some 101 years after this will was read to Mary Diltz’s family.

When I study and teach about the thing Americans callously call slavery it is always very personal to me. The words she swore out in that last will and testament are as much a part of my heritage as the stories of multiple family members who fought for freedom, justice and liberty in every war this country has fought since at least the Civil War.

When people tell me that “slavery was a long time ago” I shudder. A little piece of me dies every time I hear people deny the longterm impact of that system of inhumanity. When people say that systemic racism is a myth, I want to scream and show them this document.

It may not be real to some White people, but to those of us who come from this historical path in the “land of the free” it was not free for us but it was and still is certainly, painfully real.